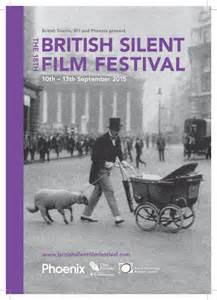

The 18th British Silent Film Festival

Posted by keith1942 on September 16, 2015

This excellent four-day event, British Silent Film and the Transition to Sound, took place from the 10th to the 13th of September at the Phoenix in Leicester. It was also supported by the BFI, The Arts and Humanities Research Council and De Montfort University. There was a programme of early films, some of which I will post on individually. And there were introductions and longer contributions on the films and the context of the transition from silent film to sound film. This event was extremely well organised. The programme was intelligent and interesting. The contributions were stimulating. There were well prepared supporting notes.

It says a lot for the organisation that the programme went off with only a couple of minor hitches, even though relying on a stack of film cans from 80 or 90 years ago. The provision by the cinema was also excellent: friendly staff, very good catering and always someone to point one in the right direction. The projection team worked well not only with many old films but with a variety of format – celluloid and digital. And then there were a bunch of talented musicians.

Thursday featured early examples of the new sound technology in British cinema. The day opened with Larraine Porter offering an illustrated talk on the period of transition. Rather like the first years of cinema this was a complicated picture, with rival sounds systems, rival companies and a competition to offer the first example. The larger competition was between the USA and Europe. The most notable intruder was Western-Electric; whilst the notable European system was Tobis Klang-film. As in the USA, whilst there were examples of disc with film, the industry soon tended to sound-on-film.

There had already been a burst of investment following the Film Act of 1927. Much of this, was speculative. As Larraine noted, of six companies launched in May 1928, only Associated Talking Picture survived into the mid-1930s. The new technology required heavy investment, both for studios and cinemas. It also required relatively quick returns, but the UK was already dominated by Hollywood studios and [to a degree] their distribution arms.

Many of these early sound films do not survive. Critical comment suggests that at least some of them did not deserve to. However, there were films of higher quality. One was the morning screening, The W Plan, from British International Pictures (1930). It was directed by Victor Saville at the Elstree Studio and used the RCA Sound System. The film was a World War I spy story and ran for 104 minutes. It starred Brian Aherne [soon to move to Hollywood] and Madeline Carroll: soon to work with Alfred Hitchcock.

After lunch Geoff Brown asked ‘Was Blackmail Britain’s First Talkie?’ As you might expect, it depends on the definition. And Geoff actually said very little about the Hitchcock film but offered descriptions and illustrations of some of the other contenders. These included the now infamous White Cargo where Tondaleyo leads the colonial administrator astray: Mr Smith Wakes Up, a comedy short with Elsa Lanchester singing: Under the Greenwood Tree, which offered a delightful sequence when the village musicians discover the vicar has purchased an organ and threatens part of their livelihoods: and To What Red Hell, a film with an anti-capital punishment message and a character frequently seen after both World Wars, the damaged veteran (all titles released in 1929).

There were two screenings in the afternoon. There was Dark Red Roses from British Talking Pictures (1929). Unfortunately sequences from the film were missing and it only ran 53 minutes. However, it had a straightforward revenge plot with the rather stilted dialogue common in this period. The second film was a jollier affair, Splinters from British & Dominion Film Corporation (1929). The company had a tie-up with The Gramophone Company ‘His Master’s Voice’, which enabled it to offer recorded music and artists. Splinters was a musical revue actually started by the top brass to entertain front-line soldiers in 1915. And it had become a box-office attraction post-war in London and on tours. There was a certain amount of presentation of the condition nears the front and then the entertainments. These were remarkably good and included an impressive female interpreter, Reg Stone.

I missed the evening screenings, just to be in a fit state for the next day. But the evening featured the US sound version of High Treason from the Gaumont Company (1929) and war drama The Guns of Loos from Stoll Picture Productions (1928).

Leave a comment