Two films starring Pina Menichelli were screened at the 2018 Il Cinema Ritrovato where we enjoyed this programme which included films and extracts also featuring Francesca Bertini and Lyda Borelli.

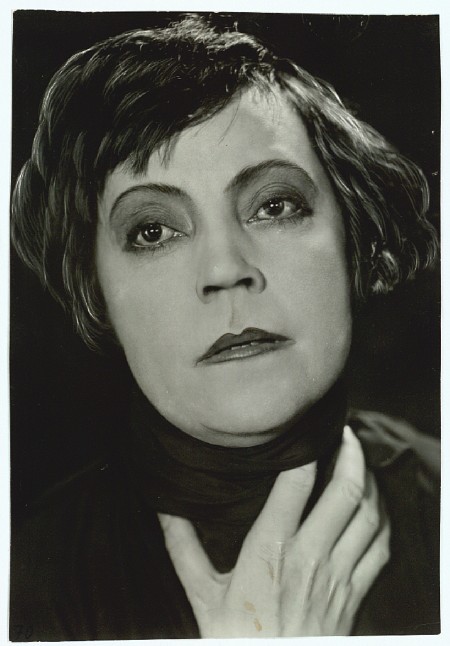

Pina Menichelli was born in Sicily into a theatrical family and started out in a stage career. She started in films in 1913 at the Roman studio of Società Italiana Cines. She achieved stardom in 1915 with the director Giovanni Pastrone in The Fire (1915, Il fuoco) for Itala. She became a popular actor both at home and abroad and her persona came embody the idea of the femme fatale. In 1919 she moved to Rinascimento Films and remained popular, despite the decline in the diva genre, until her retirement in 1924.

As is the case with other Italian films and other diva films, many are lost. We enjoyed two, an incomplete one-reel film and an incomplete feature, originally of 1800 metres.

The shorter film was from 1915, though there were not complete details. The Uncontrollable / Das Unbezwingliche was possibly a title made for Cines. It presented, alongside Menichelli, Augusto Poggioli (Mirko) and Roggiero Barni (Vilna). Both these actors also appeared in a film with Lyda Borelli in this period. The film might be the same as a title Adrift / Alla deriva from Cines, which could fit the plot and is listed with all three in the cast.

Pina is a gypsy who is an outsider in a hamlet or village. Near the opening we see her involved in a fight with another woman and the village women set upon her. She leaves with her brother, who is only seen briefly. She arrives at the estate of Vilna where she is taken on but it would seem soon ascends from servant to mistress. She comes into conflict with the steward Mirko, who both disapproves of her but he also worries about the effect on his master. Vilna seems to have a heart problem or other serious ailment. Pina’s ‘uncontrollable’ behaviour upsets him and he finally succumbs. We last see Pina once more ‘adrift’ in the countryside. Menichelli’s passionate portrayal occasions the comment ,

“She swallows flower because it is the most natural way to celebrate them. When eating an apple, she rubs it against her cheek like the caress of a lover.” (Andrea Menghelli in the Festival Catalogue).

The film follows the common conventions of the period but there are quite a number of mid-shots and close-ups of Pina. Menichelli is very effective as the truculent outsider but also as a peasant fatale. The film runs for eleven minutes, presumably at 16 fps. There are clearly missing shots but the bulk of the plot survives. The film, copied onto a DCP, had German titles with English translation.

The feature-length film was an Itala production and directed by Gero Zambuto with some input from Giovanni Pastrone. The film was adapted from a prose piece in three acts by the prolific French author Alexandre Dumas.

“At the end of World War 1, Itala Film adapted Dumas’ story, keeping the patriotic theme in the background to create a stage for the actress’s dramatic uninhibited ‘Menichelli’ mannerisms.” (Claudia Gianetto in the Festival Catalogue).

The film seems to follow the original plot but the emphasis has shifted. In the Dumas the central drama concerns an invention by Claude Ripert of

‘a vehicle able to exterminate in a few minutes thousands of men’. [plot summary].

In the film it is the infidelities of Cesarina (Menichelli) the wife of Claudio (Vittorio Rossi-Pianelli). The film opens at a party where Cesarina playfully provokes her circle of admirers. But Claudio is not only an inventor, he is a staid and moral husband. As the film progresses more and more of Cesarina’s infidelity come to light. There is an abandoned child, housed with a working class family, to whom Claudio gives support; though the child dies. There is a possible abortion. And late in the film Cesarina is planning to flee the marriage with a .lover. Menichelli is magnificently immoral. Man are their for her satisfaction. She treats her husband with contempt but when necessary vamps him.

This last occurs when Cesarina’s latest lover is actually in the pay of a circle of foreign agents trying to steal Claudio’s invention. Cesarina is pressurised into attempting to steal the plans of the weapon, which Claudio claims

“aims to destroy war!”

Cesarina now vamps Claudio’s close friend and apprentice Antonino (Alberto Nepoti). Despite Claudio’s warnings Cesarina succeed. But, whilst stealing the plans from the safe,

“Cesarina is betrayed and unmasked by the light of a ‘damned moon’.: then Claudio stops her with a gunshot. Menichelli rewards us with a textbook ending; mortally wounded, she grasps the curtains sensuously before falling to the floor enveloped in their folds, as if wrapped in a funeral shroud.” (Festival Catalogue).

In fact this is not quite the ending. We see Claudio with Antonio return to the workshop, replace the rifle he used to shoot Cesarina, and apparently happily continuing with their research. Even by the standards of the conventional nemesis of an unfaithful wife this seems extreme. It would appear to be fuelled by the power of Menichelli’s portrayal of the amoral but passionate woman,

The film suffers from censorship: something that dogged a number of Menichelli films.

“In 1918 La moglie de Claudio (Claudio’s wife) was banned from cinemas b y the Italian Censorship Board because Menichelli was “troppo … affascinante!” (too fascinating!) in the film.”(from Redi, Riccardo (1999). Cinema Muto Italiano (1896-1930)).

Menichelli’s performance is powerful and is it emphasised by the frequent use of close-ups as she toys with the male characters. Our first look at Cesarina follows a dissolve from a spider; summing up her persona in one shot. At another point, after Claudio confronts her infidelity, Cesarina gloats,

“He didn’t even beat me.”

There is also a sub-plot, retained from the original.

“two characters, a Jew named Daniel, who has fixed idea to reclaim Jerusalem for his people, and the daughter of Daniel, Rebecca, a sort of mystical visionary .” [plot summary].

This seems to be an early example of Zionism working its way into literature: Eliot’s ‘Daniel Deronda’ (1876). In the film it suggests and undeveloped romance between Claudio and Rebecca.

The film was screened from a 35mm print, about 400 metres shorter than the original. This led to ellipsis in the plot where one had to surmise events. The print was tinted and a nitrate print with French intertitles had been used in completing the Italian intertitles: provided with an English translation.

Antonio Coppola provided the musical accompaniment. And the films enjoyed his dramatic but at times also lyrical piano playing.