In the 1920s German cinema was the most accomplished in Europe and possibly the most influential until Soviet montage arrived. The giant UFA studio at Neubabelsberg was the largest and best equipped in Europe though it lacked behind Hollywood in its capital and resources. As the decade progressed the industry led the way in its production design, in the use of models and special effects, in its command of chiaroscuro [light and shadow] and then in the development of the moving camera.

Along with these skills and utilising them were a series of genres that offered unconventional stories and a distinctive style. The first of these was ‘expressionist cinema’. It embraced the style and content of a German art movement of the late C19th which itself had an unconventional look and a concern with dark, brooding topics. The approach seemed to fit well with a post World War I Germany. Not only had the state lost the war but it had only narrowly escaped a Soviet-style revolution: a political conflict which returned as the decade advanced.

This film was the first clear example of this new cinematic approach. However, some of the techniques and the look can be seen in other films of the time. And the use of light and shadow and a strong Gothic feel had been seen before the war in a film like The Golem (1915), remade as Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam in 1920)..

Caligari‘s was produced by Erich Pommer. Pommer was to be a key figure as a film producer throughout the decade. The story and screenplay were written by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz. Whilst the initial story was a dark, the design of the film was what made it so unconventional. This was produced by Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig: Reimann also designed the costumes. They imported a style that was both expressionist and theatrical. And the director Robert Wiene managed to preserve their vision and imbibed the cast with this as well.

The action takes place in a small German town when a fair opens. Among the shows is one run by Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) in which he displays a somnambulist Cesare (Conrad Veidt). The presentation is seen by two friends Franzis (Friedrich Feyer) and Alan (Hans Heinz von Twardowski). Both friends are enamoured with a local young woman Jane (Lil Dagover). The fair provides a warning of death and then a series of murders are committed though the murderer is unknown. The plot develops into a hunt and an unexpected exposure in an Asylum.

This was the original plot but it was added to; apparently by Fritz Lang who was considered as a director. The addition is an opening scene where an older man recounts the story in flashback. At the end of the film the opening pair, and the other key characters, are seen again suggesting that what we have seen may be a dream or fantasy.

The film is certainly dream-like and miles away from the naturalism that was the norm in contemporary cinema. The film made extensive use of chiaroscuro which gives an extreme contrast: this is produced both by low key lighting and by shadows painted on the sets. The sets are flat and theatrical and are full of angles which give a powerfully unsettling effect. A sense of perspective is also distorted. The acting, which is very skilled, mirrors this, with exaggerated gesture and a stiff non-naturalistic poise. This is a world of artificiality.

The settings in the film suggest a world outside the norm. The town is host to a fair, frequently a site of rule breaking and unconventional behaviour. Dark deeds occur at night, when the social order is less adequately policed. And the Asylum is the opposite of a world of order and convention.

The film has given rise to much discussion and to disagreements. One of the keenest is over the added opening and closing scenes. To a degree do they alter the substance and [crucially] the values embedded in the story. Added to this are questions of how far the film reflects or even anticipates events in Germany of the late 1920s and 1930s. Siegfried Karacauer argued that

“Janowitz and Mayer knew why they raged agaisnt the framing story: it perverted, if not reversed, their intrinsic intentions. While the original story exposed the madness inherent in authority, Wiene’s CALIGARI glorified authority and convicted its antagonist of madness.” (From Caligari to Hitler (1947).

However, M. B. White, in a review in the International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers (1987), suggests that the film remains ambiguous for audiences. He makes a key point that the expressionist style is continuous throughout the film.

“In other words, the film is structured in such a way that it represents contradictory ways of understanding the central sequence of events. This is supported by the consistency of the films mise en scène.”

But on a reviewing of the film it seemed clear that in the final sequence offers fairly conventional staging and performance, without the exaggerated style of the flashback. This is most notable in the character of Dr. Caligari where Krauss’s performance is radically altered. However White’s comments on the film’s structure seem valid. In particular, if the film acts as a metaphor for Germany in the period, then the site of an Asylum raises pertinent questions about the culture. Certainly by the time that the audience is apprised of the source of the disruption to ‘normal life’ several readings are possible.

An interesting comment on this aspect is provided by Ian Roberts in German Expressionist Cinema (2008).

“…his directorial input (Wiene), ensuring that the revised story-frame should be echoed in repeated circular imagery … point towards a very deliberate attempt to reflect the pattern of events unfolding in Germany’s streets…”

and he points to the cycle of defeat in WWI, the failed Soviet-style revolution and the re-imposition of bourgeois rule. This is an intelligent and illuminating reading of the film. And the debate itself adds to the interest of the film.

My own recent viewing made me realise the importance of the music that accompanies a screening. This had a fine piano score by Darius Battiwalla. For the flashback he provided music full of dissonance and sombre chords. But for the final sequence we heard lighter waltz-like music, which emphasised a return to normalcy from the world of chaos: with possibly a touch of irony.

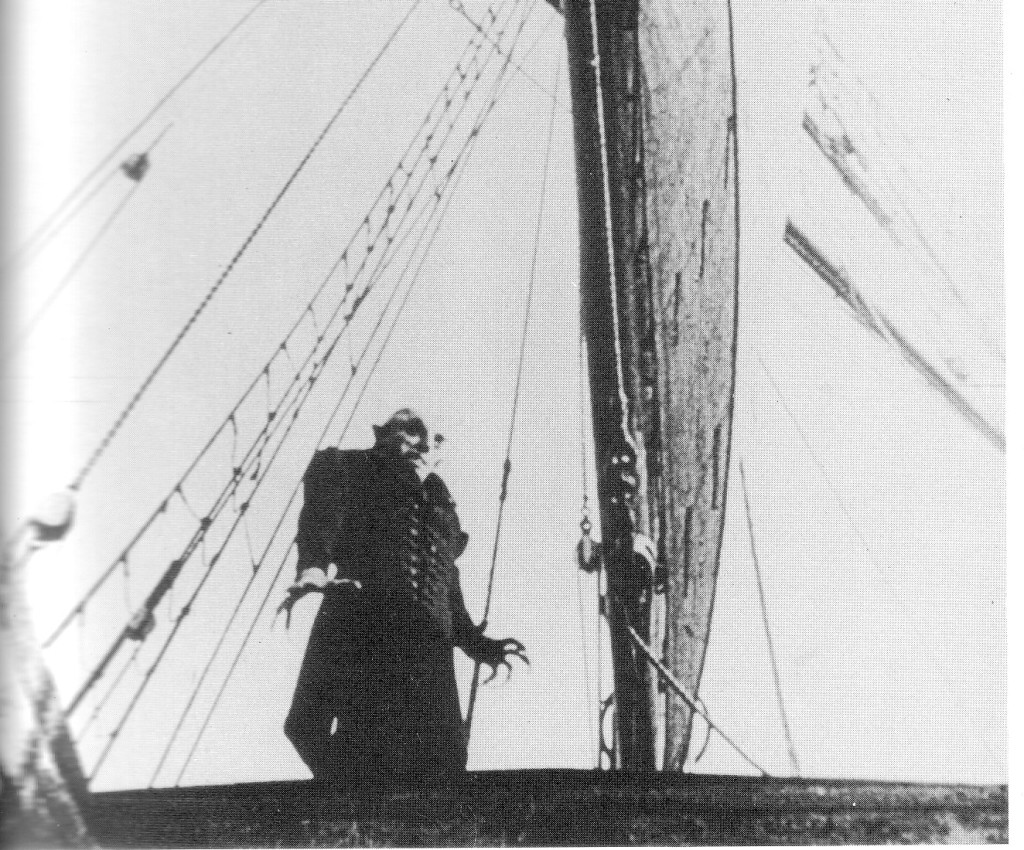

Caligari set in train a series of expressionist films though critics do not agree exactly which films fit into the form. Of equal interest is that the film is both partly horror and also an early example of a serial killer film. The former is picked up in the slightly later Nosferatu (1922) [definitely expressionist]. The latter recurs in a number of examples in Germany in this period. The later notable example being Fritz Lang’s M (1931). And these films are a key influence on the later Hollywood noir cycle.

As with film noir we have a world of chaos into which the hero descends. Given the fate of Franzis at the end he seems to be a victim hero. There is not a femme fatale but there is Caligari’s ‘obsession’ and political noirs often rely on this rather than the sexual threat. And we have the triangular relationships: in this case three younger men obsessed with the woman and the addition of the older man. Serial killer films pick up a number of aspects of film noir. In addition we have the insane killer who is at the same time apparently rational, Caligari himself. The other recurring motif is the labyrinth. Strictly speaking this film does not have a labyrinth but the sets on many occasions form corridors and passageways hemmed in by walls and buildings. At one point Franzis and two policemen descend a steep narrow staircase to a lower floor and a tightly constricted cell housing a suspect. And the ‘open air’ sequences at times resemble a maze, that parallel structure to the labyrinth. And serial killer films cross over with horror, as does Caligari. One powerful horror motif is the cabinet/coffin that house Cesare. Opening this lets loose the horror that engulfs the town and the trio of friends.

Decla Filmgellschaft. 4682 feet, black and white with green, brown and steely-blue tinting. 77 minutes at 16 fps.