The Hebden Bridge Picture House celebrated its centenary recently. It opened on July 8th 1921. Among the records still held is a listing of films screened in the early months of the venue. There are only the titles but in many cases, given the approximate time of release, it is possible to identify and fill out details. In the listing that follows I have been able to do this for almost all the films; a few remained unknown. In a couple of cases there were both British and US releases of the same name; however, US titles tended to arrive in Britain a year after their US release and thus can be distinguished from the British title. Most weeks two feature titles would be screened, likely in succession over the week.

The original release titles in this period were shot on nitrate film stock which was extremely flammable. There were a number of major incidents involving fatalities when the nitrate film stock caught fire. However, thousands of screenings did take place safely. Nowadays there are strict requirements for the screening of surviving nitrate film prints; so there are few opportunities to see such prints. Because of the silver involved in the stock,[which led to the pulping of many prints to extract this material], the prints have a luminous quality not completely reflected in safety print copies and not visible in digitised versions. The usual stock was also orthochromatic which required liberal use of certain colours of make-up. In the 1920s panchromatic film stock was introduced. This required much less use of make-up and a consequent change in appearance of characters. Alongside this was a move from acting which tended to a more apparent natural style, [i.e. less use of dramatic gesture].

In the teens and 1920s many film prints originating on black and white film stock were tinted and toned. There were also specialist stencil colouring techniques. And early examples of colour film were in use, notably in Britain was Kinechrome, an additive process where filters were used in the projection of black and white film stock. An earlier additive process Kinemacolor had fallen out of use. The first major subtractive process which actually produced a colour film print was Technicolor which developed from 1922 onwards. Whether a print was tinting or toned is often not recorded but even in 1922 this would have been a common practice.

The history of the Hebden Bridge Picture House includes a description of the opening screening of the new venue. The programme offered two feature length films. This was a change from the teens when the usual programme would have been a feature length film and a number of shorts, including newsreel, travelogues and short comedies. The listing that follows appears to mainly consist of several feature length titles, though the number vary in different weeks. It is not usually clear exactly what was in a particular programme and titles such as serials probably affected this. And in many week which was the ‘A’ feature is not necessarily clear. There would still have been shorter attractions including newsreels and, possibly, the growing number of animations. The genre of the serial very popular in the teens. These were usually screened weekly. The titles in the listing usually only appear once and in a couple of instances not as the overall serial title; presumably these were screened weekly in line with practice.

The opening screening was accompanied by a musical quartet: violin, flute, violin-cello and piano. It is likely that for the regular programmes that the music was usually a solo piano, perhaps with a quartet for special features. Large urban cinemas presenting a major release might occasionally employ an orchestra. But there would also have been screenings in this period when the films were projected silent, though that was less and less common.

British film production in the early 1920s was increasingly suffering from the competition from burgeoning Hollywood studios. The general production values of British films were lower than those of the Hollywood studios and their box office performance was lower. Increasingly British producers had problems with distribution and booking of their titles. Some of the existing studios went into decline; new companies emerged but often only lasted for a few years. It was only in the late 1920s that British production picked up for a period with the introduction of the 1928 Film Act.

Distribution was carried out by film ‘renting’ companies. Some of these were part of larger integrated companies: some were regional distributers: and some were part of major foreign companies. In the early days the French companies had been important, like Pathé. By the 1920s the growing US companies had British based renting firms; these were able to exert strong pressure on exhibitors because their product was so popular. And early example were the film of Charlie Chaplin in the teens where exhibitors need to sign up a for package of titles in order to screen those by Chaplin: this developed into a regular system known as block bookings. Increasingly in the 1920s British companies had problems getting contracts with rentals; a factor the demise of several studios.

By this date the British Board of Film Censors, set up by the Industry in 1912, was mainly effective in its certification; either U universal or A adults. The actual censorship control rested with local authorities under the acts for licensing entertainment venues. Even in the 1920s there were occasional films that ignored the BBFC certification.

The use of titles had appeared around 1900 and developed into the title card, which conveyed explanation: dialogue: and comment. there were also insert shots with printed information on such items as letters, telegrams, signs and even printed material like books. In the earlier films title cards often proceeded the action to explain what would be seen. By the 1920s title cards were inserted either side of particular actions. And some cards were ‘art’, often with producers’ logo apparent. The 1920s saw the move to limit the amount of title cards and rely more on visualisation. Britain was, as in other aspects, slow to realise this.

I have used Rachel Low’s history of this decade in British film, the relevant volumes ‘The History of the British Film 1918 – 1929 (1971) : the British Film Institute’s Collection list of titles: The American Film Institute Catalogue: IMDB: and Wikipedia. Different sources have provided film length; either in feet or meters for reels, and running times. However one cannot be sure that this is the same as the version screened in Hebden Bridge where the speed or frame rate would have been determined by the projectionist. The production details and synopsis vary with titles and I include as much as I can. Information on tinting and colour vary, though in this period quite a proportion of films would have had either tinting or toning or some of the additive colouring systems; but not all prints available for screening would have had these benefits. None of the films at this period would have had soundtracks so they relied on title cards which would have been in English, even for most foreign language titles. Invariably films had musical accompaniment.

Where the company or people involved in a title are noteworthy, I have included information on them. What emerges is a portrait of what audiences could see in a provincial town in this period; this strikes me as of significant interest. Many of these titles are now lost. Tony Fletcher has advised me –

“I viewed quite a few British films from 1921 which are held by the BFI: The Black Tulip: Jessica’s First Prayer: The Puppet Man: Ships That Pass in the Night ;Laughter and Tears; Tansy; and The Twelve Pound Look.”

I have noted in the text where a surviving print of a title is recorded. The BFI Collections also lists other materials and reviews. However, many of the titles screened do not even appear in this archive record. The problem of lost titles is greater for British film than those from the USA. Generally it is reckoned that about a third of silent film production is lost but missing titles still re-appear and/or are restored. In the case of missing films it is often possible to elucidate the pilot from surviving distributor and newspaper descriptions. Several examples are found in these listings.

“The Hebden Bridge Picture House is another rare 1920’s survivor. It opened on 12th July 1921 with Mary Odette in “Torn Sails” & Reginald Fox in “The Iron Stair” It had 954 seats in stalls and circle levels.

The cinema is Classical in appearance with two iconic pillars framing a stone recessed entrance, the building has two small shop units on either side of the stepped entrance.

The Picture House was taken over by the Star Cinemas chain in 1947. It was purchased by the local Council in 1972 and was refurbished in 1978. It now has a reduced seating capacity of 527-seats, with 299 in the stalls and 228 in the circle. Unfortunately the cinema has been flooded three times in recent years (2015, 2016 & 2020) as the the River Calder runs at the rear of the building.

The Picture House is a Grade II Listed building.”

FILMS SHOWN AT THE PICTURE HOUSE IN 1921.

The ‘Hebden Bridge Picture House’ by Kate Higham and Roy Barnes (2016) has information regarding the films just before and just following the opening.

“The predecessor of the Picture Picture was the Royal Electric Theatre, an all-wooden building …..

On the 24 June the last film shown was a;

A Kiss For Susie. USA, Pallas Pictures 1917. Black and white 1,500 m (5 reels) 50 minutes.

In “A Kiss for Susie” she is the daughter of a bricklayer, and a very good bricklayer, too. The lad who loves her is a very rich lad, as all lads should be, but, alas are not. In order to win her, he poses as a hod-carrier, certainly unromantic disguise for a wooer.”

Directed by Robert Thornby; Screenplay by Harvey F. Thew, Paul West. Produced by Julia Crawford Ivers. Starring Vivian Martin, Tom Forman, John Burton, Jack Nelson, Pauline Perry, Chris Lynton. Cinematography James Van Trees. Production Company, Pallas Pictures, Distributed by Paramount Pictures.

1 July Notice The New Picture House. Look Out For The Grand Opening 8 July. Picture House – Grand Opening Week

The Iron Stair Britain 1920 Stoll Picture Productions. 1, 820 metres – six reels

A man poses as his clerical twin to cash a forged cheque but later takes the cleric’s place when he breaks jail.

Director: F. Martin Thornton. Writers: Rita (novel), F. Martin Thornton. Stars: Reginald Fox, Madge Stuart, Frank Petley

Torn Sails Britain 1920 Ideal Film Company. 1, 500 metres / 5,000 feet – five reels

In Wales a girl loves a manager but weds her employer who dies in a fire lit by a jealous madwoman.

Director: A. V. Bramble. Writer: Eliot Stannard, Allen Raine Novel.

Stars: Milton Rosmer, Mary Odette, Geoffrey Kerr.”

Stoll Picture Productions was registered in May 1920 by theatre owner Sir Oswald Stoll and was a major company in this period. The company adapted as former aeroplane factory at Cricklewood as a studio. The company also developed a renting arm. It continued though the 1920s and the 1930s, though latter the studio was mainly used by independent productions.

The Ideal Film Company started as a distributor in 1911 and branched into production in 1916. It was a major company in the 1920s. However, due to US competition it stopped production in 1924 and distribution by 1927.

A. V. Bramble worked as an actor and director; the latter between 1913 and 1933. He was co-director with Anthony Asquith Shooting Stars (1927) a fine drama with one of the great endings. Eliot Stannard was a prolific screenwriter with 68 credits. Eight of these were for Alfred Hitchcock and his script work was influential on that director and the Industry.

The BFI has a surviving screenplay and stills.

There are also details of the town’s alternative venue for films, The Co-op Hall

True Tilda 1920 London Film Production

4,650 feet / 1,428.55 metres – five reels

An injured circus girl helps a boy escape from an orphanage and finds he is a Lord’s lost son.

Director: Harold M. Shaw

Writers: Bannister Merwin, Arthur Quiller-Couch (novel)

Stars: Edna Flugrath, Edward Carrick, Edward O’Neill

The Terror on the Range 1919 Astra Films Pathé Exchange. USA 3 reels – serial with seven episodes

Director: Stuart Paton

Writers: W. A. S. Douglas (story “The Wolf-Faced Man”), Lucien Hubbard (story “The Wolf-Faced Man”)

Stars: George Larkin, Betty Compson, Horace B. Carpenter

The Beloved Cheater USA 1919 [The Pleasant Devil]

Astra Film Corp. Lew Cody Film Corp. 1,500 metres – five reels.

Beautiful young Eulalie Morgan belongs to a strange group called “The Anti-Kiss Cult” and refuses to kiss her fiancée, Kingdon Challoner. At a dinner party one night Kingdon asks his friend…

Directors: Christy Cabanne (as William Christy Cabanne), Louis J. Gasnier

Writers: Jules Furthman (story) (as Steven Fox), Lew Cody

Joseph A. Brady cinematographer

Stars: Lew Cody, Doris Pawn, Eileen Percy.”

The Co-op Hall is no more; a supermarket now stands where it once stood.

The Picture House listing for the year continue:

15 July

Anna the Adventuress Britain 1920

Hepworth Pictures 1,915 metres / 6,000 feet- six reels

Twin sisters Anna and Annabel are as different as can be. Anna is a withdrawn art student, while Annabel is a dancer who is the toast of Paris. Annabel’s husband vanishes on their honeymoon…

Director: Cecil M. Hepworth

Writers: Blanche McIntosh, E. Phillips Oppenheim’s novel.

Stars: Alma Taylor, Jean Cadell, James Carew

Taylor played two parts and Hepworth made use of ‘double photography’ for such scenes; running the same spool through the camera twice with masking.

Cecil Hepworth was a pioneer in the development of cinema in Britain. His father was a magic lanternist and the son became involved in early film in the 1890s. He built a studio at Walton-on-Thames in 1899. In his company Hepworth Film Manufacturing Company he both produced and directed films up until 1923 when his company failed. His Rescued by Rover (1905) was a key film in developing narrative style. Alma Taylor was a popular film actress, in 1915 she pipped Charlie Chaplin in a ‘Pictures and Picturegoers’ poll. She made a number of films with Hepworth including Helen of Four Gates, actually filmed around Hebden Bridge. This latter title was screened locally at the Co-op Hall rather than the Picture House. Believed lost it was found and restored in 2017. The restored print was screened at the Picture House in 2017. The BFI has the film press book.

Duke’s Son Britain 1920

George Clark Productions. 1,800 metres / 6,000 feet – six reels.

The Duke’s heir, exposed as a cardsharp by the millionaire who covets his wife, plans their mutual gassing but goes blind.

Director: Franklin Dyall

Writers: Cosmo Hamilton (novel), Guy Newall

Stars: Guy Newall, Ivy Duke, Hugh Buckler

Guy Newall was an actor and director. His career started in 1915 and carried on into the 1930s. He set up his own production company with George Clark. They first used the Ducal Studio in London and then had a new studio built at Beaconsfield. Fox Farm (1922) is one of his notable films in which he both acted and directed. Ivy Duke was his regular partner and they married. But the company failed in the mid-20s. The BFI has several film prints including one with tinting.

The Knockout Blow Britain 1917 June

Animated posters for the National Service. 152 metres

This would seem to be a propaganda effort from the war; oresumably celebrating some anniversary..

22 July

The Admirable Crichton Britain 1918

2, 382.6 metres – eight reels

When a Lord and family are shipwrecked on an island their butler becomes a king.

Director: G. B. Samuelson

Writers: J. M. Barrie (play), Kenelm Foss

Stars: Basil Gill, Mary Dibley, James Lindsay

This has been a popular play for adaptation with two further versions, [1957 and 1968) and also several television versions.

Into the Cataract

No feature titles but an episode of a French serial does include an episode with this name;.

Two Little Urchins / Le Deux Gamines France 1920 [Gamines translates as ‘girls’]

Gaumont 9.500 metres over 12 episodes

Director and screenwriter Louis Feuillade

Camera Maurice Champreux, Léon Morizet

Stars Sandra Milovanoff, Olinda Mano, and Violette Jyl

Louis Feuillade was a master of the film serial. His most famous are Fantómas and Les Vampires. The episodes are full of mysterious actions, daring exploits and cliff-hanger endings. And, as with this title, the protagonist are often self-assured and active women characters.

The company Gaumont [Société des Établissements Gaumont] was the first major film company to involve both production and distribution, ‘vertical integration’ . The firm developed from manufacturing photographic equipment in the 1990s. Its first major film-maker was a woman pioneer, Alice Guy-Blaché.

29 July

Her Kingdom of Dreams USA 1919

1,630 metres in France; original release 2,221 m (7 reels)

Judith Rutledge, after becoming the trusted secretary of New York bank owner James Warren, agrees to Warren’s dying request that she marry his son Fred so that the bank will carry on. ..

Director: Marshall Neilan

Writer: Agnes Louise Provost

Stars: Anita Stewart, Spottiswoode Aitken, Frank Currier

Mrs. Erricker’s Reputation Britain 1920

1,760 metres / 5,780 feet – six reels

A widow compromises herself to protect her sister-in-law.

Director: Cecil M. Hepworth

Writers: Blanche McIntosh, Thomas Cobb’s novel.

Stars: Alma Taylor, Gerald Ames, James Carew

My Lord Conceit – Britain February 1921

1,839 metres / 6,000 feet – six reels

In India a count frames a runaway wife for killing her husband over the daughter of a blackmailing rajah.

Director F. Martin Thornton

Writers F. Martin Thornton, Rita’s novel.

Stars Evelyn Boucher, Maresco Marisini, Rowland Myles

Evelyn Boucher was another popular actress; she was married to writer and director Floyd Martin Thornton, Thornton worked as director between 1912 and 1925 including several early films in Kinemacolor; a pioneering two-colour additive process.

5 August

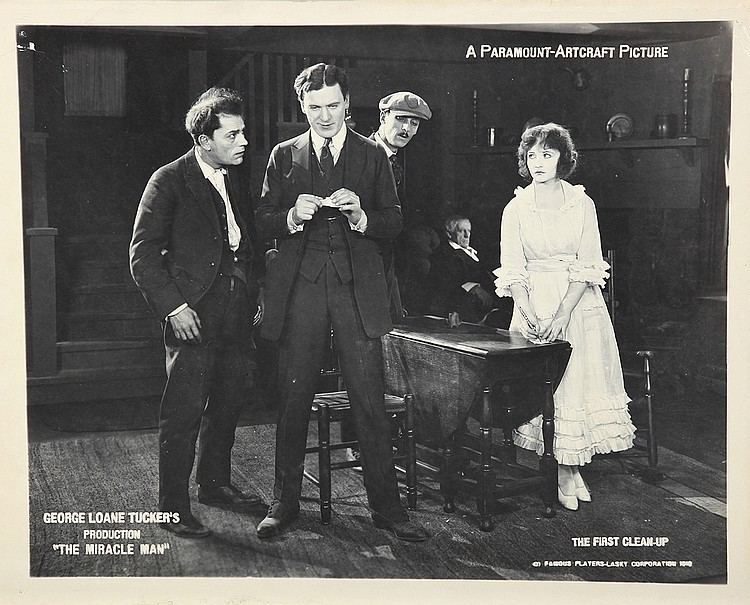

The Miracle Man USA 1919 Certified U

Pathé Camera / Mayflower Photoplay Company – 8 reels

A gang consisting of the Frog, who can dislocate his limbs, the Dope, a drug addict, Rose, who poses as the Dope’s brutalized mistress, and Burke, the leader, prey on the sympathies and contributions of Chinatown sightseers, …

Director George Loane Tucker

Writers George M. Cohan (play), Robert Hobart Davis’ play and novel.

Stars Thomas Meighan, Betty Compson, Lon Chaney

Lon Chaney was one of the most successful actors in early Hollywood. He was noted for his powerful screen presence and his use of disguise and make-up. Much of his film output, from 1913 till 1930, is lost. In the 1920s he gave brilliant performances as ‘The Hunchback of the Notre Dame’ and ‘The Phantom of the Opera’.

Innocent USA 1918

Astra Film, 50 minutes, 1.1445 metres – ( in France – 5 reels)

Kept in seclusion by her alcoholic father, Peter McCormack, Innocent knows nothing of life beyond her own house in Mukden, China. Following McCormack’s death, Innocent is placed in the care of his close friend, John Wyndham. John promises to protect the girl, …

Director George Fitzmaurice

Writer George Broadhurst (play)

Stars Fannie Ward, John Miltern, Armand Kaliz

The Flame Britain 1920

Stoll Picture Productions 1,938 metres / 6,300 feet

In Paris an orphan cartoonist loves a man with a mad wife, who dies in time to prevent her marriage to a jilted Comte.

Director: F. Martin Thornton

Writers: F. Martin Thornton, Olive Wadsley’s novel.

Stars: Evelyn Boucher, Reginald Fox, Dora De Wint…..

12 August

The Lunatic at Large Britain 1921 Certified U

Hepworth 1.561 metres / 5,800 feet – five reels

A rich madman escapes from an asylum and saves a lady from a Danish baron.

Director Henry Edwards

Writers George Dewhurst, J. Storer Couston’s novel.

Stars Henry Edwards, Chrissie White, Lyell Johnstone

Henry Edwards was a prolific actor and director who started out in 1916 and continued into the sound era up until 1937 and acting into the 1950s. He was married to Chrissie White whose career ran from 1913 until 1933. The couple were a popular and newsworthy pair.

Madame Peacock 1920 USA

Nazimova Productions / Metro I. V. six reels

Director Ray C. Smallwood

Writers Alla Nazimova (adaptation), Rita Weiman (story)

Stars Alla Nazimova, George Probert, John Steppling

Nazimova was a major star of the silent era. She was born in Russia and started a stage career there. She starred on Broadway and then entered films. Her most successful period was in teens and early 1920s. For a time she also wrote and produced her films. These included a version of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé (1923). Her sexuality was a major issue in the media.

Handy Andy 1921 Britain

Ideal Films 1.500 metres / 5,900 feet – five reels

A stable-boy poses as his cousin to foil a kidnapper and is forced to wed his sister.

Director Bert Wynne

Writers Eliot Stannard, Samuel Lover novel.

Stars Peter Coleman. Kathleen Vaughan, Warwick Ward

19 August

The Four Just Men 1921 U Britain

Stoll Picture Productions 1.517.02 metres / 5,000 feet – five reels

A gang forces rich men to donate to a charity and are betrayed by a Spanish member.

Director George Ridgwell

Writers George Ridgwell, Edgar Wallace novel

Stars Cecil Humphreys, Teddy Arundell, Charles Croker-King

There was another film version in 1939 and a television adaptation in the late 1950s.

Shoulder Arms USA 1918

Charles Chaplin Productions (36 min – 45 minutes at 17 fps) 958 metres – 3 reels

Stars Charlie Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Syd Chaplin

Chaplin was the most popular comic star of silent cinema and is likely the most famous artist from this period. The film is a propaganda piece for the US side in the war; it also advertised Liberty Bonds, loans for the war effort. Edna Purviance was a regular co-star with Chaplin in this period. His brother Syd made a career on his own as a comic.

A Gentleman of France Britain 1921 Certified U

Stoll Picture Productions 1.813.86 metres / 5,900 feet – six reels

A guardian imprisons his ward when she uncovers his plot against the king.

Director Maurice Elvey

Writers; William J. Elliott, Stanley J. Weyman novel

Stars Eille Norwood, Madge Stuart. Hugh Buckler

Maurice Elvey was a film director, occasional producer and writer and also acted in his first few films. He worked in British film from 1913 until 1958; making around 200 titles. His 1920s output is likely his best; the later decades saw him working on titles with low production values. The 1918 The Life of David Lloyd George was not released, thought lost; then found and finally released in the 1990s. His 1927 Hindle Wakes is a fine adaptation of a famous play and one of the outstanding British titles of the 1920s.

The House on the Marsh Britain 1920

London Film Production 1,600 metres / 5,250 feet (5 reels)

Mystery-melodrama about a governess in a house full of secrets, cleared up when it becomes evident that the master of the household and the housekeeper are jewel robbers.

Directed by Fred Paul

Writing Florence Warden (novel)

Cast; Cecil Humphreys, Peggy Paterson, Harry Welschman

The London Film Company was set up in 1913 by Provincial Cinematograph Theatres and operated the Twickenham Studios. The company folded in 1920 but the studios carried on; finally being used for television in the 1950s and international productions later.

26 Aug

Treasure Island USA 1920 Certified U

Maurice Tourneur Productions 1,800 metres – 6 reels at 18 fps, tinted

Lon Chaney, Shirley Mason, Bull Montana, Charles Ogle, and Wilton Tay…

Young Jim Hawkins is caught up with the pirate Long John Silver in search of the buried treasure of the buccaneer Captain Flint, in this adaptation of the classic novel by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Director Maurice Tourneur

Writers Jules Furthman, Robert Louis Stevenson novel

Stars Shirley Mason, Josie Melville, Al W. Filson

[The] Black Sheep Britain 1920 Certified A

Progress 1,519 metres – 5 reels

A vamp tries to lure a penniless heir away from a financier’s daughter.

Director Sidney Morgan

Writer Sidney Morgan, from Ruby M. Ayres serial in the ‘Daily Mirror’

Stars; Marguerite Blanche, George Keene, Eve Balfour

The Progress Film Company was a regional studio at Shoreham-by-Sea. Built before the war it burnt down in 1922.

Slaves of Pride 1920 USA

Vitagraph Company of America 1,634 metres 5 reels

Patricia Leeds is placed on the auction block of marriage by her extravagant, selfish mother and sold to the highest bidder, Brewster Howard, a wealthy man obsessed with his own importance. Howard browbeats his wife to such an extent that for revenge she elopes with his secretary, John Reynolds. The humiliated husband pursues his wife and her lover,

Director George Terwilliger

Writer William B. Courtney scenario

Stars Alice Joyce, Percy Marmont, Templar Saxe

The Manchester Man 1920 Britain

Ideal Films 1,500 metres / 5,000 feet 5 reels

A clerk loves a merchant’s daughter who elopes with a crook.

Director Bert Wynne

Writers; Eliot Stannard, Mrs. Linnaeus Banks novel

Stars; Hayford Hobbs, Aileen Bagot, Joan Hestor

2 September

Lady Tetley’s Decree Britain 1920 Certificate A

London Film Productions 1,462.15 metres / 4,8000 feet 5 reels

A Foreign Office man hires a bohemian to compromise his rival’s separated wife.

Director Fred Paul

Writers; Sybil Downing play; W. F. Downing play; Fred Paul

Stars; Marjorie Hume, Hamilton Stewart, Philip Hewland

Fred Paul [originally Fred Paul Luard, born in Switzerland] was an actor and director in British film in the 1920s.

The Devil’s Foot British 1920

Stoll Picture Productions 766.25 metres 3 reels

A family is at their dining room table, sitting upright and dressed for dinner–except they’re all dead. Sherlock Holmes must figure out how – and, more importantly, why – they were murdered.

Director Maurice Elvey

Writer; W. J. Elliott from Arthur Conan Doyle story

Stars; Eille Norwood, Hubert Willis, Harvey Braban

This was one of a series of two-reel titles numbering fifteen. Eille Norwood started acting in silent films in 1916. From 1921 he starred in a series of films as Sherlock Holmes. The majority were feature length productions, many directed [as here] by Maurice Elvey.

The Broken Road Britain 1921 Certificate U

Britain Stoll Picture Productions 1,592.28 metres / 5,000 feet 5 reels

In India three generations of a British family try to build a road despite an educated Prince.

Director René Plaissetty – cinematographer J. J. Cox

Writers; Daisy Martin from the novel by A. E. W. Mason

Stars; Harry Ham, Mary Massart, Tony Fraser

Actually shot in Algiers which proved too expensive and curtailed foreign locations for Stoll productions. René Plaisetty worked in the USA, Britain and then the French Industry from 1914 until 1932. Jack Cox was one of the really skilled cinematographers in British film. He started out as an assistant in 1913. From 1921 to 1925 he worked at the Stoll studios with frequent use of actual locations. He was skilled in the use of shadow and in inventive camera tricks. He worked on a number of Hitchcock productions including Blackmail (1929) and carried on working until the 1950s.

Ernest Maltravers Britain 1920

Ideal Films 1,524 metres 5 reels

A girl saves a rich man from his murderous father and meets him again after escaping a forced marriage and having a baby.

Director Jack Denton

Writers Edward George Bulwer-Lytton – novel, Eliot Stannard

Stars Cowley Wright, Lillian Hall-Davis, Gordon Hopkirk

Lillian Hall-Davis was an important actress in the 1920s who started out as a beauty queen. She was in an early version of The Admiral Crichton in 1918 and later was in two of the films directed by Alfred Hitchcock, The Ring (1927) and The Farmer’s Wife (1927).

9 September

The Heart of a Child USA 1920

Metro Picture Corporation – Nazimova Productions 1,783 metres – 7 reels

A poverty-stricken Cockney girl rises through incredible adventures to become the wife of a nobleman.

Director Ray C. Smallwood

Writers Charles Bryant – scenario, Frank Danby – novel

Stars Alla Nazimova, Charles Bryant, Ray Thompson

This popular novel has been adapted several times including an earlier British version in 1915.

The Tavern Knight Britain 1920 Certificate A

Stoll Picture Productions 2,053 metres / 6,659 feet – 7 reels

A Royalist and his unknown son seek vengeance on his murdered wife’s brothers.

Director Maurice Elvey

Writers Sinclair Hill, Rafael Sabatini – novel “The Tavern Knight”

Stars Eille Norwood, Madge Stuart’ Cecil Humphreys

Paris Green USA 1920 Certificate U

Thomas H. Ince Corporation 1,500 metres – 5 reels

Luther Green goes to war in France in 1917. When he comes back to his family home in New Jersey, he has a surprise following him: a beautiful French girl named Nina.

Director Jerome Storm

Writer Julien Josephson – story

Stars Charles Ray, Ann May, Bert Woodruff

Thomas Ince was an important US pioneer. He built one of the earliest studios in Hollywood and introduced a production process that became the model for the later Hollywood studio system.

16 September

John Forrest Finds Himself Britain 1920 Certificate A

Hepworth 1,481 metres / 5,035 feet – 5 reels

An amnesiac loves the poor squire’s daughter who is engaged to a rich man he thought he killed.

Director Henry Edwards

Writers Donovan Bayley – story, H. Fowler Mear

Stars Henry Edwards, Chrissie White, Gerald Ames

Great Heart / Greatheart Britain 1921 Certificate A

Stoll Picture Productions 1,691.94 metres / 5,000 feet – 6 reels

In Switzerland an invalid saves a girl from suicide after she has broken her engagement to a his rich brother.

Director George Ridgwell

Writers Sidney Broome, Ethel M. Dell – novel

Stars: Cecil Humphreys, Madge Stuart, Ernest Benham

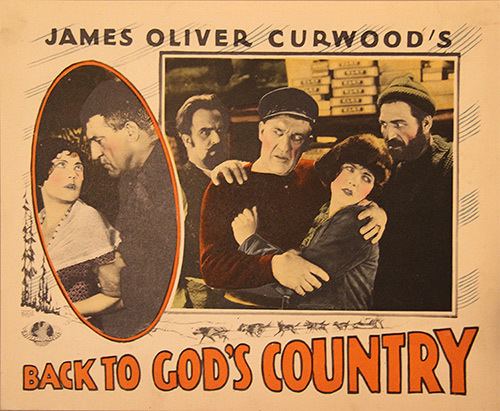

Back to God’s Country Canada 1919 unrated

Production companies Canadian Photoplays Ltd. Shipman-Curwood Company

6 reels – 1 hour 13 min at 18 fps

A woman finds herself all alone in a remote harbour with the man responsible for the murder of her father. With seemingly nobody around to protect her, she has to be resourceful.

Director David Hartford

Writers James Oliver Curwood, Nell Shipman scenario

Stars: Nell Shipman, Charles Arling, Wheeler Oakman

Nell Shipman was an early and resourceful woman film pioneer. She worked as writer, producer, actress and director in a number of films from mid-teens to the late 1920s. This is reckoned her most important title in a series of adventure films. it features an early nude scene which likely explains why the British Board of Film Censors did not provide a certificate. In the early 1920s the Boards certification were sometimes just ignored.

23 September

Humouresque USA 1920 1 hour

Production companies Cosmopolitan Productions Paramount Pictures 1,829 metres – 6 reels

Young Leon Kanter dreams of being a great violinist. His parents scrape up the money for a violin and for lessons, and Leon rewards them by becoming a great player. But as an adult, Leon finds that people want more from him than just music.

Director Frank Borzage

Writers Fannie Hurst story, William LeBaron (uncredited) Frances Marion scenario

Stars Gaston Glass Vera Gordon Alma Rubens

There is a 1946 version with Joan Crawford and John Garfield. Frances Marion worked as a screen writer from 1912 to 1940. She was one of the most accomplished writers in Hollywood; one of the few areas where women workers could shine. She also directed some titles, working [amongst others] with Mary Pickford. Fannie Hurst was a popular and frequently adapted writer including Imitation of Life (1934 and 1959). Frank Borsage was an accomplished director who also worked in the sound era; he was noted for the emotional power of many of his film, including 7th Heaven (1927) which won an award at the first Academy Award ceremony.

Carnival Britain 1921 Certificate A

Alliance Film Corporation 2,255.02 metres / 6,500 feet

An actor playing Othello in a stage production of Shakespeare’s play becomes jealous of his wife’s supposed infidelity and seems bound to kill her in the scene in which she, enacting Othello’s falsely accused wife Desdemona, is murdered by her jealous husband.

Director Harley Knoles – cinematography Philip Hatkin

Writers; H. C. M. Hardinge play “Sirocco”, Rosina Henley, Adrian Johnson

Stars; Matheson Lang, Ivor Novello, Hilda Bayley

There is a 1931 sound version directed by Herbert Wilcox. As one might guess there are several titles playing with this plot device.

Hepworth and Knoles took the film to the USA in an attempt to break into that market Such mobility was common in this period. Alliance itself was wound up in 1922. Ivor Novello was already a matinee idol and popular composer by the 1920s. He was a major star in British films and his titles include The Rat (1925, with sequels) and Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927). His career continued into the sound era.

The Narrow Valley Britain 1921 Certificate U

Hepworth 1,645 metres / 5,000 feet

A draper’s maid weds a poacher’s son when the village watch committee tries to expel her.

Director Cecil M. Hepworth

Writer George Dewhurst

Stars; Alma Taylor, George Dewhurst, James Carew

30 September

On With The Dance USA 1920 Certificate A

Paramount Pictures 1,976 metres – 7 reels

Sonia, a Russian dancer, comes to New York seeking her fortune. She marries Peter Derwynt, a young architect, but their marriage is not a good one. Sonia falls under the spell of a rich Broadway mogul, Jimmy Sutherland, whose wife is in love with Peter. The mix of relationships comes crashing apart when Sutherland ends up murdered.

Director George Fitzmaurice

Writers Ouida Bergère scenario, Michael Morton based on his play

Stars Mae Murray, David Powell, Alma Tell

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde USA 1920 Certificate A

Paramount Pictures 1,937 metres – 7 reels

Dr. Henry Jekyll experiments with scientific means of revealing the hidden, dark side of man and releases a murderer from within himself.

Director John S. Robertson

Writers; Robert Louis Stevenson, Clara Beranger scenario, Thomas Russell Sullivan play

Stars; John Barrymore, Martha Mansfield, Brandon Hurst

There are many versions of this famous story. John Barrymore was a member of the famous theatrical family. He worked in Hollywood from the teens until 1940 and was especially memorable in larger-than-life characterisation here and as Sherlock Holmes in Moriarty (1922) or impresario Oscar Jaffe in the sound title Twentieth Century (1934).

Let’s Be Fashionable USA 1920

Thomas H. Ince Productions 1,406.65 metres – 5 reels

A nice young couple moves to a community where the bonds of matrimony are not held in much respect and where it is fashionable to carry on with one not one’s spouse.

Director Lloyd Ingraham

Writers; Mildred Considine story, Luther Reed scenario

Stars; Douglas MacLean, Doris May, Wade Boteler

7 October

The Amazing Partnership Britain 1921 Certificate A

Stoll Picture Productions 1,571 metres / 5,153 feet – 5 reels

A girl detective and a reporter recover stolen gems hidden in a Chinese idol.

Director George Ridgwell

Writers; Charles Barnett, E. Phillips Oppenheim novel

Stars; Milton Rosmer, Gladys Mason, Arthur Walcott

Impéria France 1920

Production company Société des Cinéromans – A series of twelve instalments

Director Jean Durand

Writer Arthur Bernède

Stars; Jacqueline Forzane, Jacqueline Arly, Armand Boiville

If I Were King USA 1920 Certificate passed

Fox Film Corporation 2,316 metres – 8 reels

The famed poet and vagabond rogue François Villon is by odd circumstances given the opportunity to rule France for a week. Adventure and intrigue ensue.

Director J. Gordon Edwards

Writers; Justin Huntly McCarthy play “If I Were King”, E. Lloyd Sheldon scenario

Stars; William Farnum, Betty Ross Clarke, Fritz Leiber

The Broken Butterfly USA 1919

Production companies Maurice Tourneur Productions Agence Générale Cinématographique Robertson-Cole Pictures Corporation 1,500 metres – 5 reels

Before she parts from him for a while, a woman falls in love with a composer, working on a symphony, who she encounters in the forests of Canada.

Director Maurice Tourneur

Writers; Penelope Knapp novel “Marcene”, H. Tipton Steck scenario, Maurice Tourneur

Stars; Lew Cody, Mary Alden, Pauline Starke

14 October

The Curse of Greed / Le roman d’un mousse France 1914 Certificate U

Gaumont, running 1 hour 36 minutes but only 40 minutes in |Britain

A moneylender kidnaps the young son of a rich widow as part of a plot to cheat her of her fortune. The boy is sent away on a fishing boat with the intention of drowning him, but a kindly old fisherman intervenes.

Director Léonce Perret

Stars; Adrien Petit, Maurice Luguet, Louis Leubas

Léonce Perret was a talented film-maker in the teens and early 1920s. he worked briefly in Hollywood but his best work was in France. His early teen comedies are delightful and the longer melodramas very well done.

Enchantment USA 1921 Certificate U

Cosmopolitan Productions 2,130 metres – 7 reels

The frothy experiences of a vain little flapper. Her father induces an actor friend to become a gentlemanly cave man and the film becomes another variation of the ‘Taming of the Shrew’ theme.

Director Robert G. Vignola

Writers; Frank R. Adams story “Manhandling Ethel”, Luther Reed

Stars; Marion Davies, Forrest Stanley, Edith Shayne

Marion Davies was an important comedienne on stage and then in film. She was recruited to the film industry by magnate William Randolph Hearst and Cosmopolitan Productions was his company. Davies’ later career suffered from alcoholism. Among her fine performances is Show People from 1928.

In Search of a Sinner USA 1920

Constance Talmadge Film Company 1,672 metres – 5 reels

Living a life of boredom with her angelic first husband, young widow Georgiana Chadbourne begins her “search for a sinner” once her period of mourning ends. While staying at her brother-in-law Jeffrey’s apartment, she meets Jack Garrison in Central Park and, hoping to arouse the devil in him, poses as Jeffrey’s wife. Jack, an old friend of Jeffrey’s, is shocked …

Director David Kirkland

Writers; Charlotte Thompson story, John Emerson scenario, Anita Loos scenario

Stars; Constance Talmadge, Rockliffe Fellowes, Corliss Giles

Constance was one of the three Talmadge sisters, the others being Norma and Natalie. All were successful stars in the period. Anita Loos was another talented women screenwriter. She started out with D. W. Griffith and later worked with Douglas Fairbanks. One of her most famous titles was Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1928), remade in 1953 in colour and sound with, famously, Marilyn Monroe.

21 October

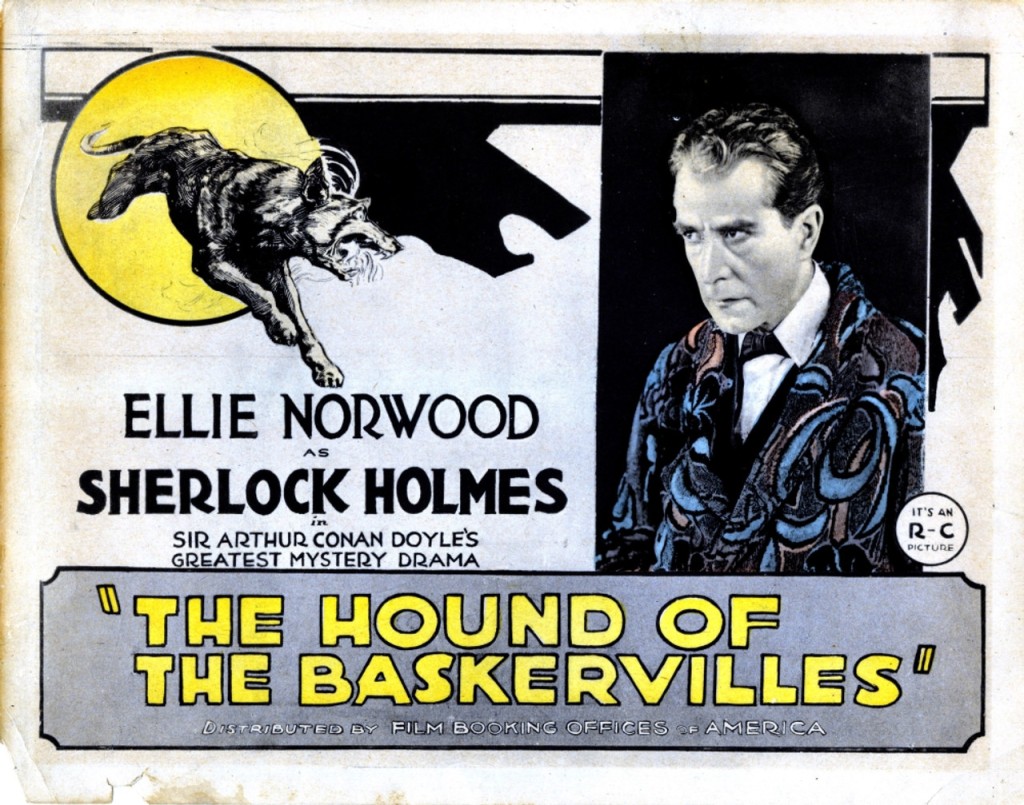

Hound of the Baskervilles Britain 1921

Stoll Picture Productions 1,676.4 metres / 5,000 feet

Sherlock Holmes comes to the aid of his friend Henry Baskerville, who is under a family curse and menaced by a demonic dog that prowls the bogs near his estate and murders people.

Director Maurice Elvey, cinematographer Germaine Burger, Art Walter Murton

Writers; Arthur Conan Doyle novel “The Hound of the Baskervilles”, William J. Elliott, Dorothy Westlake

Cast: Eille Norwood, Hubert Willis, Catina Campbell, Rex McDougall, Lewis Gilbert

Germaine Burger, along with brother Paul, was from Belgium. Walter Murton was an art director, a craft position that developed in the 1920s. The title was remade in sound versions in 1939 and 1959 and later, including television adaptations.

The National Film Archive has two 35mm prints.

The Sword of Damocles Britain 1920

British & Colonial Kinematograph Company 1,500 metres / 5,000 feet – 5 reels

A barrister’s letter proves his bride shot her aged husband on learning he was already married.

Director George Ridgwell

Writer; H. V. Esmond – play “Leonie”, George Ridgwell

Stars; Jose Collins, H. V. Esmond, Claude Fleming

The Love Expert USA 1920

Constance Talmadge Film Company 1,795 metres – 6 reels

A self-appointed “love expert” tries to play cupid with uneven results.

Director David Kirkland

Writers; John Emerson, Anita Loos

Stars; Constance Talmadge, John Halliday, Arnold Lucy

28 October

Two Little Wooden Shoes Britain 1920

Progress 1,623 metres / 3,525 – 6 reels

In France an orphan walks to Paris to visit a sick artist and finds him carousing with a model.

Director Sidney Morgan, cinematographer S. J. Mumford

Writers; Sidney Morgan from novel by Ouida

Stars; Joan Morgan, Langhorn Burton, J. Denton-Thompson

Sydney Morgan ran a small studio at Shoreham. His daughter Joan was his regular leading lady. Stanley Mumford was his regular cameraman; he later worked for the F.H.C. Company.

Garryowen Britain 1920

Welsh-Pearson 1,798 metres / 5.900 feet – 6 reels

In Ireland, a widower wins the Derby and his daughter’s American governess.

Director; George Pearson, cinematographer Emile Lauste

Writers George Pearson from the novel by Henry De Vere Stacpoole

Stars; Fred Groves, Hugh E. Wright, Moyna MacGill

George Pearson founded Welsh-Pearson with T. A. Welsh during the war and the studio survived until the arrival of sound. Lauste was the cameraman and laboratory technician until 1923. The first film produced at a new studio at Craven Park. It used art titles including a drawing or photograph.

The Old Country Britain 1921

Ideal Films 1,524.02 metres / 5,000 feet – 5 reels

A Yankee planter buys a squire’s hall, installs his exiled mother, and learns he is the squire’s son.

Director A. V. Bramble

Writers; Eliot Stannard from the play by Dion Calthrop

Stars; Gerald McCarthy, Kathleen Vaughan, Haidee Wright

4 November

The Tidal Wave Britain 1920

Stoll Picture Productions 1,898 metres – 6 reels

A fisherman saves a girl artist from the sea and falls in love with her.

Director Sinclair Hill

Writers; Sinclair Hill from the novel by Ethel M. Dell

Stars; Poppy Wyndham, Sydney Seaward, Pardoe Woodman

Why Change Your Wife? USA 1920 Certification approved

Paramount Pictures 2,186.95 metres – 7 reels

Robert and Beth Gordon are married but share little. He runs into Sally at a cabaret and the Gordons are soon divorced. Just as he gets bored with Sally’s superficiality, Beth strives to improve her looks. The original couple falls in love again at a summer resort.

Director Cecil B. DeMille

Writers; William C. de Mille story, Olga Printzlau scenario, Sada Cowan scenario

Stars; Thomas Meighan, Gloria Swanson, Bebe Daniels

Cecil B. DeMille was one of the founding fathers of Hollywood studios with The Squaw Man (1914). In the teens he was an important innovator and in the 1920s one of the really popular Hollywood film-makers. This title is a risqué comedy of which he made a series. His epics with strong conservative values were a change of style in his later career.

Scrap Iron USA 1921

Charles Ray Productions 2,056.5 metres – 7 reels

John Steel is a poor boy with a gentle spirit, but he has a natural gift for fighting. His mother is a strict pacifist, so although he has opportunities to make a career as a boxer, he refuses – until hard times force him to enter the ring despite his mother’s pleas.

Director Charles Ray

Writers; Charles E. van Loan story, Finis Fox adaptation, Charles Ray scenario

Stars; Charles Ray, Lydia Knott, Vera Steadman

11 November

The Courage of Marge O’Doone USA 1920

Vitagraph Company of America 1965 metres – 7 reels

Michael O’Doone, his wife Margaret and daughter Marge are settlers living in the Northwest. One winter day, while on a journey, Michael meets with an accident and fails to return home. Believing that he is dead, Margaret goes into a state of delirium which enables Buck Tavish, a long-time admirer, to carry her away to his cabin. When she finally comes to her senses she flees in search of Michael, leaving Marge behind. Years later, David Raine discovers the photo of a girl and determines to find her. Soon after, he meets Rolland, a man who, because of his unhappy earlier life, is dedicated to helping others. While searching in the wilds, David finally discovers the girl in the picture, Marge O’Doone. He brings her to Rolland’s cabin and it is then that they discover that Rolland is Marge’s father. Miraculously, Margaret is found and the family is reunited. —AFI

Directed by David Smith

Writers; James Oliver Curwood novel, Robert N. Bradbury

Stars; Pauline Starke, Niles Welch, George Stanley. Jack Curtis

The Woman Who Told

Title not found but there are two contemporary features with similar titles?

The Perfect Woman USA 1920

Joseph M. Schenk Productions, Distributed by First National Pictures 1800 metres – 6 reels

When Mary Blake applies for the position of personal secretary to misogynist James Stanhope, she is judged too attractive to accomplish the job. Mary returns home, makes herself unattractive and is promptly hired. Stanhope is assisting the government in the arrest of Bolshevists, and one night three revolutionaries enter the house, bind and gag Stanhope and put a time bomb under his chair. Discarding her unattractive disguise, Mary vamps the three into submission, clouts each on the head with a brass statue and saves her boss’s life. Mary’s resourcefulness forces Stanhope to give up his disdain for pretty women, and he proposes to his attractive secretary.—AFI

Directed by David Kirkland

Written by John Emerson, Anita Loos

Produced by Joseph M. Schenck

Stars; Constance Talmadge, Charles Meredith, Elizabeth Garrison

Cinematography Oliver T. Marsh

18 November

Kipps The Story of a Simile Soul Britain 1921

Stoll Pictures 1,887.95 metres / 6,139 feet – 6 reels

A sacked clerk inherits £3,000 a year, tries society, and returns to his working-class sweetheart.

Directed by Harold M. Shaw

Camera Silvano Balboni

Writers; H. G. Wells novel,

Stars; George K. Arthur, Edna Flugrath and Christine Rayner.

One of the few titles of which a print survives in the National Film Archive. The novel was adapted again in 1941, directed by Carol Reed.

Money Britain 1921

Ideal Film Company 1,371.6 metres / 5.400 feet – 5 reels

A poor bart’s daughter weds a rich secretary but leaves him when he pretends to lose money on the horses.

Directed by Duncan McRae

Writers; Edward ? Bulwer-Lytton play, Eliot Stannard

Stars; Henry Ainley, Faith Bevan and Margot Drake.

Laddie Britain 1920

Famous Pictures Film 1,500 metres / 5,000 feet – 5 reels

A society doctor makes his widowed mother pose as his old nurse.

Directed by Bannister Merwin

Stars; Sydney Fairbrother, C. Jervis Walter, Dorothy Moody

25 November

A Bachelor Husband Britain 1920

Astra Films 1.500 metres – 5 reels

Directed by Kenelm Foss

Writers; Ruby M. Ayres, Kenelm Foss

Produced by H. W. Thompson, Frank E. Spring

Stars; Lyn Harding, Renee Mayer, Hayford Hobbs

It was based on a story by Ruby M. Ayres, originally published in the Daily Mirror.

An inheritor weds stepsister who elopes with cad.

A Diamond Necklace Britain 1921

Ideal Films 1,798 metres – 6 reels

Directed by Denison Clift

Writers; Guy de Maupassant’s short story ‘La Paurue’,

Stars; Milton Rosmer, Jessie Winter, Sara Sample

A cashier and his wife suffer ten years of poverty to replace a lost necklace before learning it was fake.

The Prince Cap / USA 1920

Famous players Lasky, Distributed by Paramount Pictures 1,800 metres – 6 reels

Directed by William C. de Mille

Writers; Edward Peple play, Olga Printzlau scenario

Stars; Thomas Meighan, Charles Ogle, Kathlyn Williams

An artist in England is torn between an old flame and the now grown up little girl he has adopted.

Director William C. de Mille

Writers; Edward Peple play, Olga Printzlau scenario

2 December

The Prey of the Dragon Britain September 1921

Stoll Pictures 1,718 metres five reels

Directed by Floyd Martin Thornton

Written by Ethel M. Dell novel, Leslie Howard Gordon

Stars; Harvey Braban, Gladys Jennings, Hal Martin, Victor McLaglen

In Australia a drunkard hires a gang to kill his ex-fiancée’s husband.

Victor McLaglen was a British boxer turned film actor in 1920. In 1925 he was recruited to Hollywood and among his famous titles were a number directed by John Ford.

Lifting Shadows USA 1920

Léonce Perret productions, Distributed by Pathé Exchange 1,672 metres – 6 reels

Vania, the daughter of Russian revolutionary Serge Ostowski, escapes to America when her father is blown up by one of his own bombs. There she marries Clifford Howard, a drug-ridden man whom she comes to despise. One night while in a drunken rage, Howard attacks her, and Vania shoots and kills him. Her attorney, Hugh Mason, believing her innocent, falls in love with his client. Vania does not tell him the truth for fear of losing his love. Meanwhile, revolutionaries have pursued Vania to America to obtain her father’s papers. In defence, Hugh hires detectives to protect her. One night, a revolutionary breaks into her house and is shot by the detective. Before dying, he confesses that it was he who fired the shot that killed Vania’s husband, thus freeing her to accept Hugh’s love.—AFI

Directed by Léonce Perret, cinematography Alfred Ortlieb

Writers; Henri Ardel, Léonce Perret

Starring Emmy Wehlen, Stuart Holmes, Wyndham Standing

Anti-Bolshevik films were a Hollywood staple after the Revolution. They rarely made any mention of the US/British invasion which attempted to suppress the revolution. Reactionaries émigrés like Ayn Rand fed into the ant-left hysteria which was helped in the rise of J. Edgar Hoover in the 1920s. The hysteria continued on and off into the period of the blacklist and beyond.

What’s Your Hurry? USA 1920

Distributed by Paramount Pictures for Famous Players Lasky Corp. 5 reels 5,040 feet / 1,536 metres

To win the favour of his sweetheart’s father “Old Pat” MacMurran, race car driver Dusty Rhoades forsakes the speedway in determination to put over effective publicity for the father’s product, Pakro motor trucks.

Directed by Sam Wood, cinematography Alfred Gilks

Writers; Byron Morgan (scenario), based on ‘The Hippoptamus Parade’ by Byron Morgan

Stars; Wallace Reid, Lois Wilson

9 December

The Headmaster Britain 1921

Astra Films 1,675 metres 6 reels

A clergyman working as the headmaster of a school tries to persuade his daughter to marry the idiotic son of an influential figure in the hope of being promoted to bishop.

Directed by Kenelm Foss

Written by Kenelm Foss Based on ‘The Headmaster’ by Edward Knoblock and Wilfred Coleby

Produced by H. W. Thompson

Stars; Cyril Maude, Margot Drake, Miles Malleson

My Lady’s Garter USA 1920

Maurice Tourneur Productions, Distributed by Famous Players Lasky Corp. 1.470 metres – 5 reels

A jewelled garter with an interesting history disappears under mysterious circumstances from the British Museum. The Hawk, a criminal who has never been apprehended even though he obligingly leaves many clues for the police to follow, is suspected.

Directed by Maurice Tourneur

Written by Lloyd Lonergan (scenario), Based on My Lady’s Garter by Jacques Futrelle

Produced by Maurice Tourneur, cinematography René Guissart

Stars; Wyndham Standing, Sylvia Breamer, Holmes Herbert, Warner Richmond

The Jailbird USA 1920

Thomas H. Ince Corporation, Distributed by Paramount Pictures 1,520 metres 5 reels

Shakespeare Clancy, adroit in the art of opening safes, escapes from prison when his term still has six months to run and returns with ‘Skeeter’ Burns (Morrison), a friend who has just finished his sentence, to Dodson, Kansas, where Shakespeare has inherited a run-down newspaper and some worthless real estate.

Directed by Lloyd Ingraham, camera Bert Cann, editor Harry Marker

Screenplay by Julien Josephson

Stars; Douglas MacLean, Doris May, Louis Morrison, William Courtright, Wilbur Higby, Otto Hoffman

16 December

A Yankee at the Court of King Arthur. / A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court USA 1921

Fox Film Corporation 2,527.1 metres – 8 reels

In 1921, a young man, having read Mark Twain’s classic novel of the same title, dreams that he himself travels to King Arthur’s court, where he has similar adventures and outwits his foes by means of very modern inventions including motorcycles and nitro-glycerine.

There have been a number of film adaptation, a lost silent, sound versions, some with colour and television versions.

Director Emmett J. Flynn

Writers; Mark Twain novel, Bernard McConville adaptation

Stars Harry Myers, Pauline Starke, Rosemary Theby

All The Winners Britain 1920

- B. Samuelson Productions 1,800 metres 6 reels

A woman tries to blackmail a rich trainer into forcing his daughter to marry a thief.

Director Geoffrey Malins

Writer Arthur Applin (novel “Wicked”)

Stars; Owen Nares, Maudie Dunham, Sam Livesey

Malins is most famous for the World War I documentary film The Battle of the Somme, 1916. In 1919 he founded the Garrick Film Company and made a number of features and short films in the 1920s.

The Woman God Changed USA 1921 70 minutes

Cosmopolitan Productions; Distributed by Paramount Pictures. 1,981.8 metres 7 reels

Dancer Anna Janssen, common-law wife of Alastair De Vries, shoots him in a cafe for dallying with a chorus girl. The story opens with Anna’s trial 5 years later, and detective Thomas McCarthy narrates his version of the case.

Directed by Robert G. Vignola, cinematographer Al Liguori

Writers; by Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne, Screenplay by Doty Hobart

Stars; Seena Owen, E. K. Lincoln, Henry Sedley, Lillian Walker, H. Cooper Cliffe, Paul Nicholson

23 December

Behold My Wife USA 1920

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, Distributed by Paramount Pictures. 7 reels

Frank Armour , scion of British aristocracy and of the Hudson’s Bay Company, hears from his former sweetheart of her marriage to a rival. In revenge and to ridicule his family, he marries an Indian princess Lali. Sending her to his family home in England, he then plunges into the Canadian wilderness and into a life of dissolution.

Directed by George Melford, cinematographer Paul P. Perry

Written by Frank Condon (scenario), Based on ‘The Translation of a Savage’ by Sir Gilbert Parker

Stars; Mabel Julienne Scott, Milton Sills

In 1934, the story was filmed again by Paramount as Behold My Wife, directed by Mitchell Leisen and starring Sylvia Sidney and Gene Raymond.

The Turning Point USA 1920 50 minutes

Katherine MacDonald Pictures Corporation; Distributed by First National Exhibitors Circuit. 6 reels

Upon finding themselves in financial difficulties because of the failure of the Edgerton-Tennant Company, New York socialites Diana and Silvette Tennant decide to work as society hostesses. Also affected by the business failure is James Edgerton, who is in love with Diana. Employed by wealthy E. H. Rivett to stage a fashionable party, Diana encounters Colonel Carew who harasses her with questions about a murder in Reno which has clouded her name. Driven from the party by his questioning, Diana is pursued by Carew to her apartment, followed by Mrs. Wemyss, a widow jealous of Carew’s attentions to the girl. Diana’s good name, her love and honour are at stake until Edgerton comes to her rescue, forcing a full revelation of the Reno affair and thus clearing the path for a union between Diana and her benefactor.—AFI

Directed by J. A. Barry, cinematographer Joseph Brotherton

Based on The Turning Point by Robert W. Chambers

Stars; Katherine MacDonald, Leota Lorraine, Nigel Barrie, William V. Mong, Bartine Burkett,

William Clifford

The Rotters Britain 1921

Ideal Films 1.524 metres / 5,000 feet – 5 reels

Directed by A. V. Bramble

Based on a play by H. E. Maltby

Stars; Joe Nightingale, Sydney Fairbrother and Sidney Paxton.

A headmistress recognises a married JP as her ex-lover and stops him from sentencing the Mayor’s son. Stanley Holloway’s first film

30 December

The God of Luck / Le Dieu du Hazard France 1919

Société Générale des Cinématographes Éclipse, listed as running around 90 minutes

A husband asks his wife to persuade a wealthy young man to invest in a declining company.

Director Henri Pouctal

Writer Fernand Nozière

Stars; Gaby Deslys, Félix Oudart, Georges Tréville

Eclipse was founded in 1906 and produced [among other titles] popular serials. It suffered decline at the end of the First World War along with other French companies.

Ruth of the Rockies USA 1920

Ruth Roland Serials; Distributed by Pathé Exchange. 9,000 metres 30 reels

In New York City breezy Bab Murphy comes into possession of a trunk with the insignia of the Inner Circle, a gang of crooks, who have their headquarters in Dusty Bend along the Mexican border but also operate in New York. The gang trails the trunk to ownership by Bab and, for it and a jade ring that is mysteriously sent to her, a series of adventures begin as she heads for the Bend.

Directed by George Marshall

Written by Frances Guihan, Based on “Broadway Bab” by Johnston McCulley

Produced by Ruth Roland, camera Al Cawood

Stars; Ruth Roland, Herbert Heyes

15 episodes of which only two survive, Chapter titles: The Mysterious Trunk: The Inner Circle: The Tower of Danger: Between Two Fires: Double Crossed: The Eagle’s Nest: Troubled Waters: Danger Trails: The Perilous Path: Outlawed: The Fatal Diamond: The Secret Order: The Surprise Attack: The Secret of Regina Island: The Hidden Treasure

Shore Acres USA 1920

Screen Classics inc. Distributed by Metro Pictures Corporation. 1,823 metres 6 reels

Apparently lost, a period newspaper gives the following description: “Shore Acres is a story of plain New England folk on the rock ribbed coast of Maine. Martin Berry, a stern old lighthouse keeper, forbids his spirited daughter Helen to speak to the man she loves! It is Martin’s fondest hope that Helen will marry Josiah Blake, the village banker. Helen refuses to obey her father, and elopes with her sweetheart on the “Liddy Ann,” a vessel bound down the coast. Her father learns of her departure, and insane with rage, he prevents his brother, Nathaniel, from lighting the beacon that will guide the vessel safely out through the rocks of the harbour. Desperately the two men battle together in the lighthouse—one to save the vessel, the other to destroy her. A sou’easter is raging, and during their struggle the “Liddy Ann” goes on the rocks and the passengers are left to the mercy of the storm. The scene fairly makes the nerves tingle with excitement. What befalls thereafter is thrillingly unfolded in this picturization of the greatest American play of the century. Shore Acres is a big human drama of thrills and heart throbs, replete with delicious humour and tender pathos.”

Directed by Rex Ingram, Maxwell Karger, cinematographer John F. Seitz, editor Grant Whytock

Writers; by Arthur J. Zellner scenario, based on ‘Shore Acres’ by James A. Herne

Star; Alice Lake, Alice Terry uncredited

Director Rex Ingram and Alice Terry first met during the making of the film in 1920. They would eventually marry over a weekend during filming of The Prisoner of Zenda in 1922.[5]

The Audacious Double Event – There is a British release of a similar title without the ‘audacious’ .

Given this was the New Year period this may have been some sort of special event. There are a couple of earlier films of the same title. The 1914 version was produced by Hepworth and there is a slight overlap in the plot?

The Double Event Britain 1921

Astra Films five reels

After her father, a country clergyman, loses large sums of money his daughter recoups his losses by becoming the partner of a bookie.

Produced by H.W. Thompson

Directed by Kenelm Foss

Written by Kenelm Foss, play Sidney Blow and Douglas Hoare

Starring Mary Odette Roy Travers Lionelle Howard

There was a sound version of the play in 1934.

There is also a US title with ‘audacious’.

Always Audacious USA 1920

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, Lasky Corp.

Comedy of the mistaken identity of a rich young man and a layabout.

Director: James Cruze

Currently the Picture House retains a single 35mm projector alongside a modern digital projector. They are able ocassionally to screen 35mm prints though the limitations on accessing this format from archives is a restriction .