The Berlinale, or Berlin International Film Festival, is one of the great Film Festivals. It has a vast and varied programme. Alongside the offerings of world cinema, mainstream productions, documentaries and experimental fare are well designed retrospective programmes. This year, in a treat for cinephiles, the Festival offered a focus on the era of Weimar Cinema, German film production from 1918 to 1933.

“In the heyday of German film-making, a variety of styles developed such as Expressionism and New Objectivity, inspired in part by American methods, a division of labour developed which led to greater professionalism and specialisation in many film production jobs.”

‘Expressionism’ is fairly well-known as a film movement, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920) is the famous example. The ‘New Objectivity’ was an artistic movement which in some ways was a reaction against Expressionism. The films espoused a more naturalistic style, in keeping with their socially conscious themes. A late and favourite example of mine is Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 1930).

Some of the titles from the Weimar period are rightly famous; The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann, 1924) by F. W. Murnau with Karl Freund; and Metropolis (1927) from Ufa and Fritz Lang; both films were trailblazers of the Silent Era. But this retrospective offers a fresh insight,

“But with ‘Weimar Cinema Revisited’, that prolific period of German film itself becomes the subject of a review for the first time. The attention is primarily on work that is often omitted from the core list of Weimar films.”

There were 28 titles and 18 short films screened over the ten days of the Festival. I have seen a variety of early German films but I had only see three of four of these titles before. So the retrospective offered a feast of new cinematic treats. The majority of titles in the programme were screened twice. Many were from the silent film period and had live musical accompaniments. There are several restoration screening in digital formats but 16 of the features were on 35mm film with one title on 16mm. There were three strands to the programme.

“Exotic – worlds are portrayed in a variety of ways and genres. Travelogues, already very popular in early cinema were also a common genre in the Weimar era.”

There were early ethnographic films and traits of ‘Orientalism’.

“The mountain film, at the time a primarily German genre, can also be seen as a variety of the exotic.”

“Quotidian – In turning to the New Objectivity of the second half of the 1920s, elements of contemporary reality and social issues were incorporated into the narratives of many films.”

The programme included titles by the film-maker Gerhard Lamprecht, I saw several of Lamprecht’s films in a programme at Il Cinema Ritrovato and he appeared a talented and socially conscious film-maker of the period.

“History – Lavishly produced period films, such as Der Favorit der Königen (The Queen’s Favourite, 1922) were very popular in the Weimar Republic.”

We also had an early version of the much characterised Ludwig II of Bavaria which offered an interesting comparison with the several later versions.

The Features: [in the order that I saw them].

Der Katzensteg (Regina, or the Sins of the Father) was released in 1927. It was directed by Gerhard Lamprecht and adapted from a novel of the same name from 1890 by the noted author Hermann Sudermann. It is a period drama set in the times of the Napoleonic wars. The novel’s popularity would seem to be confirmed by their being three other film adaptations and it seems that films set in the Napoleonic period were popular in Germany in the 1930s. The key characters are a Baron and his son, Boreslav (Jack Trevor); a Vicar whose daughter, Helene (Louise Woldera0, is romantically involved with Boreslav; and at the other end of the social scale a drunken coffin-maker whose daughter, Regine (Lizzy Arna), works at the Baron’s castle. The first act of the film presents events in 1797 with the French invading Prussia. There is an act treason which sets in motion a chain of catastrophic events. The acts of the fathers haunt the children.

By 1813 the wars near their end but revenge continues to blight the lives of the children. The conflicts come together in a powerful and tragic conclusion. This film was a dramatic tour de force though if often used conventional situations. Stylistically it was filmed with real panache. In particular the opening sequences involving night-time conflicts between French and Prussian troops were really gripping.

The film was projected from a 16mm print from the Deutsche Kinemathek. It was old and the definition was only fair but one could still enjoy the excellent use of the moving camera and effects like superimposition. The screening also benefited from a fine accompaniment by Maud Nelissen. Much of her music offered a slow and sombre accompaniment and there were finely timed silences at key moments.

Kameradschaft – La tragedie de la mine – Comradeship (1931) is a famous German/French co-production. It was directed by the highly regarded George Wilhelm Pabst. Based on a mining disaster of 1906 the film shows how German rescue teams rush to aid their French comrades after an explosion. The film opens by stressing the borders that separated France and Germany, including a reference to the French occupation of the Ruhr industrial area in 1921.

The digital restoration was introduced by Julia Wallmüller from the Deutsche Kinemathek. She explained that there had been two versions on release, German and French. The German release did not fare well but the French version was popular. In Germany a final ironic ending was cut leaving a more upbeat conclusion. The restoration now included that ending.

The film is bi-lingual, German and French. It is extremely well done and blends effectively the actual film footage with studio recreations. We follow the general direction of the disaster but also are encouraged to identify with sympathetic individuals from both communities. The underground sequences combine almost documentary representation with tension, pathos and relief. The film focuses on the working class communities either side of the border and there is a sense of class and craft solidarity. The management and authorities remain in the background. The changed ending in Germany was symptomatic of the future when the organised German working class failed to halt the rising Fascist Party. Predictably the Nazis did not like the film.

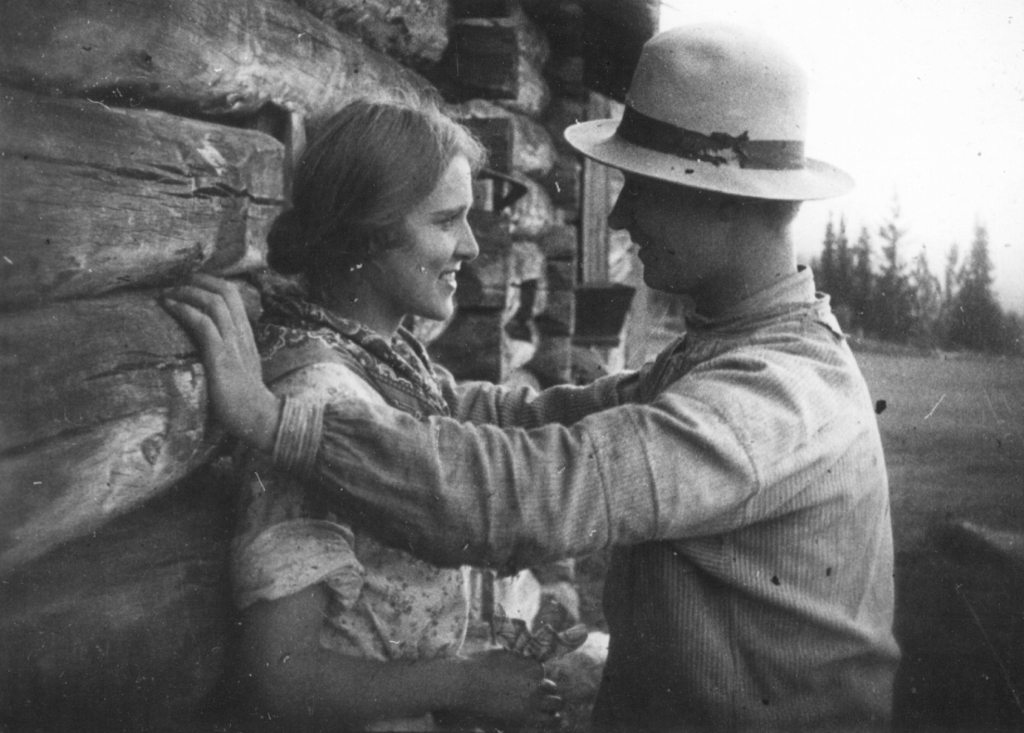

Der Kampf ums Matterhorn / Fight for the Matterhorn (1928) dramatizes events leading up to Edward Whymper’s famous ascent of the key Alpine peak. The first six reels of the film chronicle the relationship between Whymper (Peter Voß) and Italian guide Jean-Antoine Carrel (Luis Trenker). Carrel lives in the village of Breuil with his wife Felicitas (Marcella Albani), his mother (Alexandra Schmitt) and step-brother Giaccomo (Clifford McLaglen): plus two dogs. The mountain drama is filled out with a triangle of passion with Giaccomo attempting to stir up enmities because of his desire for Felicitas. I found this melodrama distracted from the main mountaineering narrative. It appeared to be an attempt to provide dramatic aspects to the false rumours that Whymper had cut a rope when the later tragedy occurred.

The mountain sequences, with early attempts on the Matterhorn by Carrel and Whymper, are excellent (this is 1860 and 1863). The film generally blends location work with studio shots effectively. And it enjoys striking panoramas across the Alpine mountains. The cast involved skilled mountaineers and there are impressive shots of climbing on rock faces and steep snow slopes.

The film also has memorable canine moments. The house dog, a terrier, at one point nips at the dancers during a village celebration. The outhouse dog, a Labrador-cross, has an epic sequence. It races over snow, ice and rocks to call Carrel to aid his wife who, fleeing Giaccomo, has fallen down a slope on the glacier.

In the last three reels the film moves to the tragic events of 1865. Following the record fairly closely we see the party led by Zermatt guide Michel Croz with Whymper and the competing party from the newly formed Italian Mountaineering Club led by Carrel. Whymper reaches the summit first but there is a fall on the way down with the loss of four lives. The ascent is well filmed though the latter stages are presented through an iris (a telescope – long shots): presumably as they were not able to film high up the mountain.

There follows the accusation of a cut rope against Whymper. Here the film dramatises and we see Carrel climb up the Matterhorn and return with the rope to vindicate Whymper. The drama here works better than in the earlier reels which provide a reference point. But again I found it distracted from the central mountaineering story which is visually stunning. The DCP had introductory titles explaining that the restoration relied on several different print versions. The restoration and transfer were at 4K which produced an excellent and well-defined image. I did think the location and reconstruction shots were distinguishable, down I assume to the harder edges of digital. We enjoyed a piano accompaniment by Maud Nelissen: she made the melodramatic scenes passable and the mountain sequences imposing. The film runs for 117 minutes. There are shorter versions, including a 9.5mm version of three reels.

Menschen im Busch, Ein Afrika-Tonfilm (1930). We had an introduction from a member of the Deutsche Kinemathek who provided the background and context to the film. The film-makers, Gulia Pfeffer and Friedrich Dalssheim, filmed in the interior of Togoland [later part of Ghana and the Togolese Republic]. The land had been a German colony before World War I and post-war it became a British Mandate: a method used by the British to grab land in many places. This political dimension was not addressed by the film. Whilst the film used footage shot on location the sound was dubbed in Berlin. It seems that migrants from the territory now living in Berlin were used to ‘voice’ the dialogue in the film. There is also some African singing and a musical score, the latter fairly European in style. The use of actual African voices was a first in ethnographic film; a parallel to Edgar Anstey’s film Housing Problems (1936).

The film opened with an introduction from the former German Governor. We had been warned that his comments were littered with what are now ‘politically incorrect’ descriptions. He compared the Africans to ‘children’ and described their culture as ‘inferior to European Civilisation’. All was not lost, because most of his talk was heard over images of the coast line of the territory. The opening was very well done, we watched fishing boats landing their cargoes, battling through the surf to the beach. This, like the rest of the film offered excellent camera shots and movements.

The film presented a day in the life of the Ewe people in Chelekpe village. In fact the majority of the film followed one family, a village man, his two wives and children. The narrative ran from daybreak to late evening. There were meals, work, and leisure. The village had a division of labour, both in harvesting and hunting, and in the technologically dependent activity of weaving. Animals were a full part of the village life: goats, pigs, chickens, and some smaller animals we could not identify. In the evening there was a religious/social dance ritual. This was accompanied by drumming as both men and women, some in special costumes, swayed and rotated. The dancing and drumming reached a frenzied climax before darkness fully fell. We viewed a 35mm sound print.

Christian Wahnschaffe, Teil 1: Weltbrand (Part 1: World Afire) was directed by Urban Gad in 1920 and in a digital form ran 80 minutes. This was the first of two films adapted from a novel by Jacob Wassermann. I do not know the novel but the plot of the films suggested a vast picaresque narrative. The opening title explained that the film is set in 1905 in several European countries. Conrad Veidt plays the titular role. Christian is the son of a wealthy industrialist. He lacks purpose though he has secret desire for his engaged step-sister. Spoilt and lacking direction Christian is introduced to a popular Pairs-based dancer with whom he begins an affair. Eva (Lillebil Christensen) is a man-eater and later in the film she has another affair with a Grand Duke, [a stand-in for the Romanov Tzar]. This links the film to the Revolutionary Year of 1905, though it is not actually presented in name. In the course of the film we have become acquainted with anarchists and a secret group called ‘The Nihilists’: appropriately their political programme is never explained. They are involved in protests and suffer in the repression ordered by the Grand Duke. In one scene he watches a s a machine gun opens up on a civilian demonstration. In the later stages the plot develops round an envelope of secret papers. The story ends pretty badly for everyone, except the Grand Duke and his henchmen: but Christian does survive.

The film followed the style of many early films in this period. Full of parallel cutting between characters and events, often in very short scenes. These move at speed and it becomes quite complicated following the plot. It is however full of conventional tropes and stereotypes, and combines motifs from several familiar genres of the period. In that sense it was probably easy for a contemporary audience to follow. Stylistically the production is not that well done. The editing leaves a certain amount to be desired though it was not clear how much was due to missing footage. The cast are reasonable but it is not one of Veidt’s great performances though he plays a familiar persona.

Christian Wahnschaffe, Teil 2: Die Flucht aus dem Goldenen Kerker (Part 2: The Escape from the Golden Prison, 1921) is a sequel. The ‘golden prison’ is Christian’s family home where he feels bored and guilty over his privileges. A different friend takes him to a working class district in the hope of excitement. This they find, and Christian assists, a poor prostitute attacked by her pimp. He thus meets a young social worker, Rose (Rose Müller). Partly due to her attraction and partly due to acquiring a social and religious conscience, Christian starts to ‘give all he has to the poor’. However, in this slum we find few ‘deserving poor’ and an amount of ‘undeserving poor’. The film resembles Part I in that once again the story ends badly for most characters.

This film has a coherent narrative thread and avoids the endless parallel cutting. So it works in a more constrained and effective manner. In addition, whilst the film has the same director as Part I, it has new scriptwriters. Most noticeably it has a new cinematographer, Willy Hameister. His work offers frequent high angle shots of the slums. The exterior use both low-key lighting and effective tinting. It looks much better than the first part. And there are some excellent set-pieces in the slum tenements as the mass of working class denizens are involved in varied agitations. Part 2 seems a much better film than Part 1.

Stephen Horne provided the accompaniment for both films. He worked effectively with Part 1 but Part 2 provided greater scope for drama and emotion. Stephen is a multi-instrumentalist, so we had several instruments; one at least, the accordion, provided a musical motif for working class scenes in both films. Escape from the Golden Prison is a definite film to see but watching the whole two-part drama makes better sense and the contrasts alone are entertaining. Both films had been transferred to DCPs.

Der Himmel auf Erden (Heaven on Earth, 1927) was a social comedy. The lead character, Traugott Bellmann (Reinhold Schünzel, who also directed the film), is a Member of Parliament who achieves fame by condemning centres of vice. He specifically names the night club ‘Heaven on Earth’. However, newly married, he discovers first that his new father-in-law sells the copious amounts of Champagne consumed in the club; then, that it belongs to his step-brother, not seen for years. His embarrassment creates problem in both his public and personal life.

The situation opens in a very witty manner with a delightful satire of parliamentary action. The night club itself is only mildly unseemly and hardly at all immoral. The main consumption is the champagne. The dancing girls are leggy but not overtly sexy. And the nudes on the drapery are really quite prim. The comedy in the club is probably stretched out too long: I found the humour and wit dissipated at times. But it come together in a great and comic climax And the scenes of the moral guardians and some of Bellmann’s discomfiture are very funny.

The film was screened from a pretty good 35mm print. Maud Nelissen provided a score that included light sequences, lively dances and touches of ragtime.

Mit der Kamera durch Alt-Berlin was a nine minute film from 1928 on 35mm screened prior to a feature.

“It finds traces of old Berlin in the modern city. It juxtaposes drawings and engravings made about 1800 with the 1928 reality.“

Central to the tour is water and the River Spree. The director is unknown.

Die Unehelichen, Eine Kindertragödie (Children of No Importance, 1926) is an example of a genre of the period addressing the exploitation and oppression of children and often dramatising a ‘child tragedy’. The director was Gerhard Lamprecht, but here in the socially conscious mode. I had seen this film before in a programme at I Cinema Ritrovato and it was more typical of the work of the director than Der Katzensteg.

We had an introduction by Daniel Meiller who explained that as well has having a long career in German film Lamprecht was also an avid collector of films and film memorabilia. He was a key person in advocating archives in post-war Germany. And his collection formed the basis of the Deutsch Kinemathek when it was set up in 1960.

The film centres on four children who have been placed with foster-parents. The adults are mainly interested in the income. The man drinks and is often violent, the woman is feckless. An early scene shows the trauma for the children when their pet rabbit is killed. The two older children are Lotte (Fee Wachsmuth) and Peter (Ralph Ludwig). Lotte succumbs to the poor treatment and dies. Peter is given hope by kindly neighbours and then a woman who is prepared to adopt him. However, this prospect recedes when Peter’s father, who works on a barge, turns up and wants his son as additional labour. Peter has to pass through a traumatic and climatic ordeal before the film closes.

“The basis for making the film was an official report from a society for the protection of children against exploitation and cruelty and socially committed director Gerhard Lamprecht brought to light a deplorable state of affairs that was widespread in the Weimar Republic.”

Seeing the film again I was impressed. This time it was a digital transfer rather 35mm. It is very well done and the children are convincing. However I did find that the narrative and representations were rather conventional and used stereotypes to a degree. Once again we have the ‘deserving’ and undeserving’ poor with not a great degree of nuance in the characterisation. The film does effectively offer contrasts. The film opens with a privileged child of a bourgeois household playing in the garden and watched, on the other side of the railings, by Lotte and Peter. Late in the film, when Peter appears to have found an equivalent home, he plays with friends in a well-appointed garden.

Frühling Erwachen (Spring Awakening, 1919) was another ‘Eine Kindertragödie’. However this film dealt with school students in their late teens: at a time before the ‘teenager’ had been invented. The film was based on a Franz Wedekind play dealing with the ‘sexual tragedy of youth’. There are a group of students but at the centre are Moritz (Carl Balhaus) and Melchior (Rolf van Goth). Moritz’s family would seem petty bourgeois. His father harbours ambitions beyond Moritz’s abilities. But Melchior, from a bourgeois family, [like Hubble in The Way We Were, 1973], is gifted and finds school life easy. We also follow the boys’ relationship with two girl students. Melchior has a close relationship with Wendla (Toni van Eyck) who lives alone with her mother. Whilst Moritz engages with Else (Ira Rina). Her father is a successful businessman. Ilse, the vibrant person in the group, organises a party at her home on one of his business trips. There is sexual experimentation. And a veiled description of this in a notebook causes Moritz to face expulsion, despite his innocence. This incident is the one that mainly determines the tragic outcome.

The film was directed by Richard Oswald. I have seen his films before and found him a pedestrian film-maker. Spring Awakening is well produced and the cast are good. But the drama only takes off in individual scenes; shots in the cemetery are well done. And the treatment of awakening sexuality is timid. There is a sequence by a river with a young couple: I deduced rather than knew that coitus occurred. Of course, there was Weimar censorship. But there are films, like those adapted from Wedekind’s other plays, that are more explicit.

We had a good 35mm print to watch. And Stephen Horne provided a well composed score that was complimentary.

Die andere Seite (The Other Side, 1931) was an early sound version of R. W. Sherriff’s 1928 play, ‘Journey’s End’. So we had a German cast playing the British soldiers on the Front Line in 1918. The lead actor was Conrad Veidt as the commanding officer, Richard Stanhope. Once I got used to the German language for ‘Tommies’ I was really involved. Intriguingly we had two German performances of ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’, one the English original and one a German variant.

The film follows the play very closely. Its makes really good use of the moving camera, high and low angle shots, sound effects and inserts shots. The claustrophobia of the dug-outs, the squalor of the trenches and the desolate landscape between the lines are very effective. I thought that it worked better than the 1930 British/US version. The last time I saw that film it struck me as rather studio bound, even with a pretty good cast. And I also found this version superior to the newly released British version in colour and widescreen. That film adds additional scenes, apparently to fill out the pilot. In fact these rather dissipate the drama. And Die andere Seite works better at placing the conflict and battle. In an early scene Stanhope shows the positions on the map and one has a clear sense of the lay-out of the opposing sides. We enjoyed an original 35mm sound print.

Opium (1919) is a film I had seen once before but this was a new restoration presented on digital. We had an introduction on this from Stefan Drößler and Andreas Thein. Using nitrate elements at the Düsseldorf and Munich Archives and at the Austrian Film Archive they achieved a longer version closer to the original. Notably they also reconstructed the vibrant tinting (lots of reds) of the film. This was a transformation from the version I saw a few years ago.

“Made during a censorship free period, Opium combined the thrill of the exotic with them titillation of the erotic . . .”

The film is full of scenes of indulgence in opium and the vivid and bizarre dreams that the smokers experience. These in particular stand out in the film,

“[Robert] Reinart and his cameraman Helma Lerski developed a brilliant, hallucinatory cinematic language . . .”

Another of Reinart’s films is Homunculus (1916), a serial about a Frankenstein creation. This also has vivid tinting and hallucinatory sequences. The plot of Opium is picaresque, taking us from the USA to China, to Europe, back to the USA, to India and back again. There are supposed scientific investigations and good deeds. But there are also extra-marital affairs, long-term revenge journeys and, predictably with drug addicts, hospitalisation and death. This is a bizarre but powerhouse film. Keeping, I would think, the audience agog for its 91 minutes.

Die Carmen von St Paul (Docks of Hamburg, 1928) is another late silent that I have seen before on film. Here it was a digital transfer, but the standard of these has been good. Like so many other films it enjoys a variation on the famous heroine of Prosper Mérimée and Georges Bizet. This version uses recognisable character alternatives and some of the plot. But it avoids the final tragedy of the opera. As the alternative title suggests the film make extensive use of the harbour and port at Hamburg: the ‘St Paul’ area is the red light district. There is an amount of location footage of ships, machines and workers and these create a bustling sense of the port, whilst outside of the working hours it becomes quieter but closer to noir settings.

Klaus (Willy Fritsch) works for a shipping company and finds himself on night duty. Thus he meets Jenny (Jenny Jugo). She is involved with a gang of smugglers, though they are as much involved in theft as contraband. Poor Klaus is smitten. However, Jenny is younger and less cynical than the original. Even so Klaus loses his job and becomes involved in the gang. Jenny is flirts on the edge of crime. She also performs at a local night club. One number is a mock cycling race by women in sparse ‘sportswear’. Later, when a rival for Klaus appears, a motor racing driver, Jenny coolly claims to be a ‘fellow sportsman’. The plot develops parallel to those in the opera but this is a seedy underworld of a [then] modern urban industrial area.

St Paul is the home of vice and the gang are what was then called ”harbour rats’. So we watch criminal acts and innocents branded as guilty. Some of this is quite conventional. But the club, like the harbour sequences, has a distinctive atmosphere which is convincing.

“[the film] imbues putative everyday scenario with the mythical aura of of a Brechtian ‘Jenny the Pirate’. Travelling shots along the waterfront lend the film an almost neo-realist character….”

The cast are generally good but is Jenny Jugo who stands out. She has an on-screen charisma from the moment she emerges from a wet male attire on Klaus’ ship. Another of her films worth seeing is Looping the Loop (Die Todesschleife, 1928).

Abwege (The Devious Path, 1928) was a second film directed by G. W. Pabst. We enjoyed an introduction by Stefan Drößler who provided a context for the film. It seems that in a parallel to the ‘Quota Quickies’ in Britain following the 1927 Film Act, cheaper German productions were made in this period to fulfil requirements for indigenous film screenings. The cinemas, like Britain, were dominated by the Hollywood product. I think this showed as the narrative of the film was stretched to fill out the 98 minutes of running time. But it looks good and the main part of Irene, the bored wife of a busy and successful lawyer, is played by Brigitte Helm. She looks superb and the supporting cast play out their characters extremely well. Deprived of her husbands attentions Irene embarks on alternative pleasures. These includes exotic night clubs, a possible affair and illicit substances. These exploits, especially a long sequence in a night club, are extremely well done.

“…the great realist of the Weimar-era cinema, uses a marital crisis to paint a shimmering portrait of society. Camerawork [by Theodor Sparkul] that is as unchained as Irene herself delves into a whirling world of luxury and vice.”

These scenes are more about visual pleasure than plot development, but they do entrance. The film ends up more moral than many of Pabst other films, with a light touch almost worthy of Ernst Lubitsch. The film was screened from a DCP which looked really good and the tinting was fair. And Richard Siedhoff, a young pianist from Weimar, provided a deft score.

Ihre Majestät die Liebe (Her Majesty, Love 1931) was sound film starring Franz Lederer as Fred, the younger brother in a family combine who possesses fatal charm but little ready capital. Lederer, a Czech-born actor, was a popular lead in German film in this period. One of his most notable appearances was in G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (Die Büchse der Pandora, 1929). To annoy his family Fred spurns a union with a wealthy investor and marries the barmaid at a night club he frequents. Lia (Käthe von Nagy) is already smitten with charming but feckless Fred. The family opposition mean that their romance has to surmount a series of obstacles. On the way the film satirises the attitudes of the snobbish bourgeoisie.

The film was directed by Joe May, a successful director and producer in German Cinema. He gave Fritz Lang his start in films and like him ended up in Hollywood. In fact, Hollywood quickly made a copy of this films with the same English-language title, also 1931. The film has delightful humour and some fine witty lines. Much of it is due to

“The supporting actors [who] are the stars in this tempestuous film operetta. In a mad dash to a surprise ending, a colourful chorus of song numbers, sketches and artistic tomfoolery put those minor roles at the centre of attention – “

One of these being Szöke Szakall, later S. Z. Sakall, amongst whose Hollywood films is Casablanca (1942, as Carl at the famous club). The screening offered a 35mm sound print.

Sprenbagger 1010 (1929) had its title translated to the memorable Blast Excavator 1010. The title refers to a new invention by young engineer Karl (Ivan Kobal-Samborsky). It will increase production at the mining company dramatically. I did wonder if the technology actually made sense, but in the film managers and colleagues find his design brilliant. And, indeed, later in the film it does appear to work, though this relies on editing separate shots in parallel.

“Set against the background of the Leuna Works complex and the coal fields of central Germany, first tie director Acház-Duisberg (son of the head of I. G. Farben) made an apologia for the age of the machine.”

Building the machine near a rich seam of coal means disrupting the tranquillity and livelihoods of a quiet pastoral setting. Predictably there is opposition, including within Karl’s own family. And the conflict is dramatised romantically as Karl is desired both by fellow engineer Olga (Viola Garden) and local land-owner Camilla (Ilse Stobrawa).

“The violent clash of rural idyll and industry, machinery and romanticism is matched by the cinematic collision of industrial reportage and melodrama.”

What stands out in the film is the cinematography by Helmer Lerski [again] and the editing. There are extensive sequences of montage, especially when we reach the dramatic climax. The film had an early sound track of music. The score by Walter Gronostay has been recreated for the 35mm print that we saw. However, it was mainly in the C19th orchestral tradition and I did not find that it matched the images. The credits included the young Fred Zinnemann as an assistant cameraman.

Das Abenteuer einer schönen Frau, Deutschland 1932: Regie: Hermann Kosterlitz

Das Abenteuer einer Schönen Frau (The Adventure of Thea Roland, 1932) starred Lil Dagover in the title role. She is an independently-minded woman and a successful sculptor. A new commission sends her looking for a suitable male model. She finds him at a local boxing gymnasium: boxers were a popular film type in this period. However, her chosen subject is Jerry (Hans Rehmann), an English policeman and police boxing champion visiting Berlin for a fight. Inevitably romance, or at least desire, evolves. Dagover convinces as the independent woman but Rehmann has his work cut out as the English Bobby. We do see him in one scene directing traffic in London.

The film works hard at generating humour. But what stands out is in the latter part Thea has a child whilst unmarried. Despite the social contempt she receives Thea sticks to her child and independent living. The conclusion is rather more in keeping with the then current mores but in the course of the narrative it seems that Thea is a ‘new woman’ and Jerry is a ‘new man’. There is a sense of equality in their relationship including in the care of their child.

We enjoyed a another good 35mm print. It is a film with some excellent production design including quite distinctive props, as in the nursery. The film was directed by Hermann Kosterlitz, later Henry Koster, whose films in Hollywood include several of generic similar titles such as My Man Godfrey (1957).

Das Blaue Licht, Eine Beglregende aus den Dolmiten (The Blue Light, A Mountain Legend from the Dolomites, 1932) was one of the most well-known titles in the retrospective. Leni Riefenstahl, having established her cinema presence acting in mountain films, now took on the mantle of director as well as star. In an introduction we were told that the film had been re-edited at different times. In the later 1930s the screenwriter, Béla Balázs, who was a known Marxist, lost his screen credit. However, the version screened now was from the personal collection left by Riefenstahl and this had provided the basis for a restoration presenting the film as originally released in 1932.

The film has a very simple plot but is blessed with some very fine mountain cinematography. Two climbers arrive in a mountain village to attempt the local massif. A picture catches their attention and they are told the legend of Junta. Decades earlier the young woman, an outsider in the village, is viewed with suspicion. The situation is exacerbated by a ‘blue light’ which has appears half-way up the mountain pinnacle that overlooks the village. The light first appeared after a massive avalanche and is visible at the time of a full moon. Several men from the village have died attempting to climb up to the light when it appears at night.

However, Junta climbs up a down with immunity and regards the light as personal treasure. A painter befriends her. And one night he and Junta set out for the source of the light. They are followed by a villager intent on also reaching the light. These are impressive mountaineering sequences. There is predictably a fall. But there is also a hidden grotto on the massif. It is here that there is an explanation of the magical light. But in solving this mystery the way is open for the villagers to exploit the mountain, leading inexorable to a tragedy which is the reason why Junta is still remembered.

Riefenstahl plays Junta as a type of ‘earth spirit’: in some ways the character is reminiscent of the parts she played in the films of Arnold Frank, a key exponent of the ‘mountain film ‘. The film was screened from a 2K DCP which provided an effective transfer of the film.

Ludwig der Zweite, König von Bayern (Ludwig II of Bavaria, 1932) was a sound portrait of this frequently-filmed C19th monarch. The film was subtitled ‘Destiny of an unfortunate man’ (‘Schicksal eines Unglücklichen menschen’). The film treats of the last decade of Ludwig’s life, when his obsession with building castles took full flight. So the only nod to Wagner is a portrait and a telegram announcing his death. As the Brochure notes Ludwig is surrounded by ‘fawning courtiers and officials.’ The political class attempt to occupy him by indulging his castle mania. But as his breakdown proceeds he is placed under the care of a psychiatrist. The ‘unfortunate’ king descends into paranoia and finally death.

The film was directed by William Dieterle who also plays Ludwig. His performance is impressive but the film struck me as repetitious. I cannot remember a film with so many dissolves: more than half the scene changes use this device. Many of the sets are impressive and Charles Sturmar’s cinematography is well done. But other characters remain ciphers. I think if I had not seen later versions by directed by Helmut Käutner (1955) and Luchino Visconti (1973) I would have found some of the narrative puzzling.

The Brochure notes that the film

“which did not hide Ludwig’s fascination with the naked male body drew intense criticisms from Bavaria. When the Bavarian censorship board refused to intervene, Munich’s police commissioner imposed a ban on showing it on the grounds that it was ‘a danger to public order’.

Ludwig has clearly exercised a fascination for film-makers as there is also an earlier title from 1922. We had a 35mm print and an excellent accompaniment by Günter Buchwald.

Brüder (Brothers, 1929) was a ‘proletarian’ film directed by Werner Hochbaum. The basis for the plot was a famous strike in Hamburg docks in 1896.

“Made on the eve of the global economic crisis, Werner Hochbaum’s look back at the failed Hamburg dock-workers strike is a reminder of the achievements in social welfare that the trade unions and social democracy brought about in the Weimar Republic. This film, Hochbaum’s feature début, received support from both the Unions and the Social Democratic Party.”

The focus of the narrative is a leading union member and his family, which includes a wife suffering [apparently] from consumption, his own mother and their daughter. He is a key mover when an individual worker is knocked down by a foreman. In fact, at times the plot reminded me of Eisenstein’s Stachka (Strike, 1925) which would have been seen in Germany by this date. The film dramatises the solidarity of the striking workers and the unholy alliance of the state authorities and police with the capitalist management. There is a mass meeting of the dock-workers where, despite the caution expressed by the official, section after section of the work force support the call for a strike. What I found odd was that two policemen appeared to be sitting in on the meeting. I asked one of the staff from Deutsche Kinemathek and she thought that this was a legal requirement during Weimar. There was a system of strike pay but it appears to have been a pittance.

Late in the film our protagonist is arrested on a trumped-up charge. But a demonstration by his comrades enables him to escape. However, as in history, the workers are forced back. But, in a possible reference to Eisenstein’s Bronenosets Potemkin (Battleship Potemkin,1925) there is a colourised red flag.

We viewed the film on a pretty good 35mm print. The film was full of location shots which, I was told, were all filmed for the production by Gustav Berger. He was an adept cameraman, using high and low angles and some notable travelling shots. We had a fine score by Stephen Horne who seemed as inspired by the film as I was.

Heimkehr (Homecoming, 1928) was the second film in the programme directed by Joe May. The story follows two German POWs held in Russia in 1917, Richard (Lars Hanson) and Karl (Gustav Fröhlich). In terms of the drama and screen time Karl is the main character but Hanson had the primary credit. Rather than imprisoned in a camp Richard and Karl have been left unguarded to operate a river ferry: however, they are in the wilds of Siberia, so escape seems daunting. In between ferrying passengers, mainly it would seem fellow prisoners sent to work in the mines, Richard incessantly talks about and describes his home and his wife Anna (Dita Pario). When they finally escape Karl must carry the exhausted Richard but eventually Richard is recaptured, and Karl continues his escape journey.

A year later Karl arrives in Hamburg and visits the flat looking for Richard. He is still absent, but Anna is entertained by Karl’s stories of the duo’s life in captivity. She offers Karl the use of one room. Inevitably a romance develops between Anna and Karl, though they try to resist this. Inevitably Richard returns and finds how relationships have changed in his absence. The climax and resolution of the film essay the conflicting demands of friendship, jealousy and desire.

The film is very well done. The film relies extensively on sets, but these work fine and there is some fine low-key lighting. The cast is good. There is a delightful sequence when Karl arrives at the Hamburg flat and, thanks to Richard’s descriptions, he both recognises the layout and notes the changes. There is some very smart editing late in the film as parallel cuts show us the responses of the different characters as the drama unfolds.

“Producer Erich Pommer had just returned from Hollywood where he had made two war films, Hotel Imperial and Barbed Wire. With this story of a love triangle, he brought American production methods to bear on Weimar cinema.”

The film avoids excessive militarism; this is a downbeat story of soldiers and war. The film starts in March 1917 and I rather expected that the Russian Revolution would figure at some point. But the date is more to do with the war which, unlike in the West, ended in a treaty between Germany and the new Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. So, Richard’s release is signalled when a Red Guard tells prisoners that they can ‘go home’.

“In the tradition of earlier intimate dramas, the film focuses on the psychology of the three protagonists. In the process, it creates a model of masculinity – unusual for the way the subject was normally dealt with in Germany at the time – that is utterly devoid of military bearing.”

Whilst this is true the representation of masculinity is not that different. The resolution of the film completely focusses on the two men and after the point at which they leave the flat we do not see Anna again. This is a rather cavalier treatment especially as Dita Pario is excellent in the role. We enjoyed a good 35mm print. The piano accompaniment was provided by Richard Seidhoff, a young musician who performs in Weimar. His score was good, and I am sure I will hear him again at silent screenings.

So Hamburg became the most filmed city in the retrospective after Berlin. The docks obviously fitted well with the dramatic plots of the popular genres. And it also provided a range of interesting locations which the films were happy to exploit.

Der Favorit der Königin (The Queen’s Favourite, 1922) was entertaining but offered a plot that was pure hokum. The Queen of the title was clearly a stand-in for Queen Elizabeth of England. The film is set in London and among the many references are the new colonies in the North Americas, including Virginia, though we never actually travel there. The main plot device is a ‘Grey Death’ that mysteriously strikes down people. The opening, in a noir-like street as the bodies are carried away, is very effective. There follows a tavern frequented by body snatchers, a breed supplying doctors with cadavers since the Church and State forbid dissection of the dead, on pain of death.

However, leading doctor, Pembroke, believes that dissection is only way to establish the causes of the ‘Grey Death’. When he pays the full penalty of the law his assistant Arthur Leyde continues his work. Complicating the narrative is the mutual attraction between Arthur and Pembroke’s daughter Evelyne, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen. But Evelyne is the object of desire of Lord Surrey who is already the Queen’s paramour.

It is the solving of the mystery of the ‘Grey Death’ which results in the resolution of the film, I would rather not spoil the fun by explaining this. But I can point out that Arthur’s treatment consists solely of his standing by the bed of a sufferer till the mystery illness passes. Presumably the limited medical knowledge of late C16th explains why no-one seems to notice that he does not actually carry out any medical procedures.

“In the suspenseful period film, [low on suspense actually], the stated goal of the doctors is to “liberate science from its shackles and the people from a scourge”. In 1922, it was no doubt a provocation – and not only in catholic Bavaria – to articulate a democratic ideal that was a resounding call to the powers that be and the clergy that “the people’s voice is the voice of God.”

However, the film is more interested in the elites than ordinary people who are represented as superstitious and gullible. The main characters are rather melodramatic. The film is from early in the 1920s, a period when acting developed closer to what we regard as a naturalistic performance. The performers are variable and there is a tendency to stand and declaim, a hang-over from the teens. The 35mm print was good. and Stephen Horne worked well in developing some psychology among the protagonists.

Whilst popular cinema in the 1920s was focused on fictional dramas there were a variety of non-fiction films. This was the decade in which John Grierson coined the word ‘documentary’ for films that presented the actual world about us. Germany, as elsewhere, produced films that utilised film shot in and about recognisable places, peoples and institutions. The travelogue, one of the earliest examples of feature-length non-fiction film, was popular. There were also experimental and avant-garde film-makers who offered films that emphasised cinematic techniques and explored the way that film represented reality.

Im Auto durch Zwei Welten (Across two Worlds by Car, 1927 – 1931) is a travelogue but also an adventure.

“For this prototype road movie, race car driver Clärenore Stinnes (1901 – 1990) and Swedish cameraman Carl-Axel Söderström covered 46,758 kilometres. Travelling in an Adler sedan and sponsored by companies like Bosch, Aral, Varta and Continental, they drove through 23 countries and once round the globe – ..”

The epic journey took two years and started out east from Frankfurt, through the Balkans, the Middle East, Iran, the USSR to Siberia, across the Gobi Desert into China and Japan. Crossing the Pacific it continued up the backbone of South America along the Andes: then by boat to the USA, ending up in New York. Another boat across the Atlantic bought them back to Europe and finally Germany. Söderström claimed that he did ‘more pushing than filming’ and in fact there are long stretches where the filming is sparse. All we see of the USA is the West Coast and then the East Coast. There was also a van or truck accompanying the sedan, presumably all the stores and equipment. After the journey Stinnes had the film edited by Walther Stern and added a commentary and a musical score by Wolfgang Zeller. The commentary accompanies the images but these are intercut with shots of Stinnes talking direct to camera. The score is European in style even for the far-away places.

The sponsorship by German firms was an important aspect of the production. In her opening comments Stinnes stresses the German composition of the team, then noting that the cameraman is Swedish. She adds, in a comment that is mirrored by others later in the film, that Scandinavian are Germanic ‘fellows’. The filming does tend to stress the backwardness and poverty of the lands through which much of the journey travels. In fact, even discounting the boats, the round-the-world journey is only partly driven. There are frequent sequences where local people are persuaded or paid for hauling the vehicles, often through mud, sand or rocky terrain. The most gruelling, for the labourers, is when they cross the mountains and deserts of Peru. So her comment that ‘the automobile makes the big world small’ is as much rhetoric as actuality. The film is interesting but conventional: Stinnes was not Riefenstahl. However, she clearly was an independent and adventurous woman. The screening used a 35mm sound print.

Milak, Der Grönlandjäger (The Great Unknown, 1927) is a fictional drama presented in documentary mode. An opening title explains that the film was inspired by the exploits of polar explorers such as Roald Amundsen and Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Elements of both explorer’s stories figure in the plot. Filmed largely on location in Greenland and Norway’s Spitsbergen archipelago, the film combines impressive landscape footage with ethnographic observation.

“With their athletic way of filming in the open air, the camera staff from Arnold Fanck’s ‘Freiburg camera school’ used the natural world as a key player, even blowing up ice sheets to create high drama.“

The film follows an expedition crossing Greenland to a high point in the north. The team consists of explorers Svendsen, Eriksen and Inuit Milak, an expert dog handler [who is titular in the German title]. During the course of the expedition we also watch their families at home waiting to hear how they managed.

The film seems to have been successful: critics at the time suggested that it was ‘Germany’s answer to Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922). The connection is obvious. Apart from being set in Polar regions the films also features Inuit. The difference is that whilst Flattery did not just record but directed Nanook and his actions, in this film the Inuit are placed in a completely fictional narrative.

I found the tropes from other polar stories, especially that of the British expedition led by Captain Scott, lacked conviction. The expedition is trekking across Greenland and there is a contest, a US team with the same objective. They struggle over ice slopes, snow slopes and crevasses. Eriksen sickens and we follow a sequence where he does a ‘Captain Lawrence Oates’ style exit from the tent in a snow storm. Then the team run low on food and face the possibility of failing to reach stores, fuel and safety. The plot avoids the tragedy of Scoot and his team, but the sequences are clearly modelled on that actual disaster.

What undermines some of the narrative is that the film combines excellent location work with rather obvious studio sets. This is the case in the sequence where Eriksen attempts ‘suicide’ during a storm and in the scenes where lack of food and exhaustion threaten the team and the expedition.

The team also use two dog teams, more like Roald Amundsen. Twice the dog teams fall into crevasses, the second time they do not survive. In each case it is down to an oversight of Eriksen. I have to confess that I hoped his fellows would save the dogs rather than Eriksen. What makes it odder is that one dog does survive. But it is clearly not one of the dog team, all black or dark-haired huskies. This sole survivor is brown and more like German Shepherd/Labrador cross, [the former then known as Alsatians]. This is a shame, because the location work and the sequences of the Inuit are well done. The ethnographer parts of the film work better than the dramatic episodes during the expedition. The film was screened from pretty good 35mm with Günter Buchwald essaying a balancing accompaniment between actuality and fiction.

The Light of Asia (Die Leuchte Asiens, 1925) was a joint German/Indian co-production directed by Franz Östen for Indian producer Himansu Rai. They worked on three productions in the 1920s, titles that are rare survivors of Indian cinema’s silent heritage. In this film English tourists are regaled by an old Buddhist monk with the story of a C6th monarch who has to choose the material and the spiritual; a choice that figures in several Indian mythic tales. Essentially most of the film is a flashback to this story. The film uses actual Indian locations and cast for its narration.

The film had been transferred to DCP and had an added music track by Willy Schwarz and Ricardo Castagnola, Schwarz playing traditional acoustic instruments and Castagnola contemporary electronic music. Willy Schwarz provide d an introduction in German but I noted that he used the terms ‘Bollywood’ and ‘4 by 3’, neither strictly applicable to Indian Silent Cinema,. I also found the score problematic The soundtrack was far too loud during the opening credits: I saw other audience members winching. The staff did lower the volume but I still found it too loud, especially with the harder tones of electronic music. So I left shortly after the flashback commenced. I checked later and the level of sound had been requested by the composers. This is a tricky issue as composers and performers are entitled to have their music presented as they intend. But in the case of film the music is an accompaniment and I do think it has to be subordinated to the image. In fact, I have noticed in recent years that increasingly some accompaniments are too loud or forceful and distract from the image. I suspect this is a follow-on from the increasing use of ‘live music’ as a way of attracting audiences to silent film screenings. Fortunately I had seen the film previously. At Le Giornate del Cinema Muto with live accompaniments on traditional Indian instruments.

Song, Dire Liebe eines armen Menschenkindes (Show Life,1928) is a classic melodrama jointly produced by Eichberg-Film GmbH, Berlin and British International Pictures. The German title translates as ‘dire love of a poor human child’.

“Moving between dive bar and cabaret, ocean liner and night train, the German-British co-production represented Weimar cinema’s first foray into the milieu of European ex-pats in a colonial setting, which was very attractive for western foreign markets.”

The main protagonist is John (Heinrich George) an entertainer who has a knife-throwing act and who is stranded in an unidentified Asian port. On a beach he rescues a young Chinese woman, Song, (Anna May Wong) from assault. He recruits her into his knife throwing act, which, with her physical charms, becomes a success in a cheap bar. But John’s old flame and mistress, Gloria (Mary Kid), a successful dancer, reappears. Implausibly John prefers the scheming Gloria to Song: in the late 1920s how many female stars would one prefer to Anna May Wong?

Desperation leads to criminality and a fateful accident. John is duped regarding Gloria and Song, who is devoted to John, is caught and suffers between them. There are some fine sequences including late in the film when Song herself has become a successful dancer. The cinematography by Heinrich Gärtner and Bruno Mondi, makes excellent use of low-key lighting. The contrasting sets, low-life and high-life, dramatise the conflicts on screen.

We had a fair 35mm print from the British Film Institute and a suitably dramatic accompaniment by Günter Buchwald.

Morgen Beginnnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933) was directed by Werner Hochbaum who also directed Brothers. This is a film that fits in the New Objectivity and shares some qualities with the ‘proletarian films’. The film opens with Robert (Erich Haußmann) nearing the end of his sentence for manslaughter. On the day of his release he expects to find his wife Marie (Hilde von Stolz) there to meet him. But Marie has returned home late after a tryst with an admirer. She oversleeps. Both spend the day searching for their partner in Berlin. So the city, or a particular area, is itself another character.

The film has a dazzling array of techniques:

“using documentary images, expressionist lighting, subjective camera angles, and experimental sound and picture montages..”

At times there are multiple superimpositions and these also lead the audience into the flashbacks that explain Robert’s and Marie’s situation. Robert was the kapellmeister of a restaurant orchestra. Marie worked in the bar and the killing resulted when he intervened to stop Marie being molested by the owner/manager. One of the ironies is that Marie’s admirer, (possibly lover) is the new kapellmeister.

The narrative uses melodramatic tropes including, apart from missed meetings, a stopped clock, a un-received letter and unhelpful neighbours. The brochure notes that the film was made after the end of the Weimar Republic. This sort of [mildly] left-wing film was past its time. The film was attacked on the grounds that the director,

“politicised his methods to the same extent that he resurrected the rhetoric of the old avant-garde.”

Hochbaum made films up until 1939 but died quite young in 1946. We had a 35mm print but without subtitles. In fact I found the plot relatively straight forward to follow. And I read after the screening that the film had

“minimal, often deliberate incomprehensible dialogue’.

We did at one point see the un-received letter which [I suspect] explained something about Marie’s admirer/lover.

A programme of experimental film opened with two short films by Hans Richter,

“a pioneer of Germany’s absolute film movement,”

The movement also included Walter Ruttmann, Oskar Fischinger and the Swede Viking Eggeling. Dedicated to abstract art they had particular interests in light, time and imagery that suggested musical analogues.

Filmstudie 1(928) offered a five minute film with a montage of bodies, faces, glass eyes and geometric shapes.

Inflation (1928) ran for just three minutes with a combination of numbers and images.

“Within seconds, a wealthy man reading a newspaper becomes a beggar, the zeros on the banknotes multiply – right up until the stock physically collapses.”

Das Lied vom Leben (The Song of Life, 1931) ran for 55 minutes. The film was directed by Alexis Granowsky. It uses surrealist imagery and music by Walter Mehring and Hans Eisler. The film has a narrative but uses montage and extensive superimposition. A young woman, Erika, lives with her mother in poverty. She agrees to marry a rich baron. The wedding reception is a kaleidoscope of privileged but corrupt members of the groom’s class. Finally Erika flees and is tempted to ‘end it all’. She is saved by a young man and later they have a child. However, Erika has to undergo a caesarean to enable the birth. Audiences found the operation sequence shocking. Unsurprisingly the film sparked a battle with the German censors and the film was at first banned outright.

“Originally only approved for viewing by ‘doctors and medical professionals’.”

We had one short film projected silently; otherwise all the titles were films with soundtracks. The German film industry pioneered sound-on-film as it did with other technical developments and stylistic techniques. The Tri-Ergon system was, for many years, the dominant sound system in Europe. Whilst early sound lacked the quality developed later this 35mm print and the shorts on DCP were perfectly adequate for dialogue, noise and music.

Short Films 1: ‘Quotidian’ (‘Kurzfilme I: altag’) was one of two programme. The five films shared some of the themes and approaches of ‘New Objectivity’. They were projected from 16mm and 35mm prints.

Polizeibericht überFall (Police Report of a Mugging, 1929) made by Ernö Metzner was a film running for 21 minutes. The short drama offered a critical, equivocal and ironic comment on urban life. The prop which provides the focus for a series on interlocking scenes is a one-Mark coin. This is initially dropped and then picked up by a passing man. However, he becomes the focus first of a potential ‘mugger and then of a prostitute and her pimp. Wherever he goes or even runs an obstacle appears. The irony is that the coin is a dud.

“ The censor’s office regarded this social satire, shot in avant-garde style, as nothing more than a “crime film” that “due to its accumulated brutality and harsh acts was likely to have a lowering and deadening effect”. It banned the film. “

Markt in Berlin (Open-air Market in Berlin,1929), was made by Wilfried Basse and ran 18 minutes. “The weekly market at Wittenbergplatz, from the vendor set-up in the early morning hours to the clean-up in the afternoon, provides an opportunity for sympathetic observation of the customers.”

Wo Wohnen alte leute (Where the Old People Live, 1932).

“Artist Ella Bergmann-Michel presents an old-age home in Frankfurt’s Westend neighbourhood as a “functioning living organism”. While the elderly in the dark, inner city building descend into isolation and loneliness, the modern architecture of the newer building, with its light-flooded spaces, promotes socialising. “

Fishfang in der Rhön (An der Sinn) (Fishing in the Rhön Mountains, 1932), also by Ella Bergmann-Michel.

“who arranges collages of fish pictures for natural history books, films her husband angling in a crystal-clear river.”

The idyll is slightly disrupted by a cat stalking prey. For a contemporary audience this offers a premonitory warning. As the Brochure notes the film was made in the ‘final summer of the Weimar republic’. Ella was an abstract artist, influenced by Constructivism: both abhorred by the Nazi regime. During the Nazi era, the Michels survived by fishing and farming.”

Alexanderplatz Überrunpelt (Alexanderplatz Unawares, 1932 – 34) was a series of fragments from an unfinished film. Unfinished because

“the film was never completed because the director [Peter Pewas] was arrested by the Gestapo and the footage seized.”

The charge was treason, though I have not found the details. Pewas returned to film-making but had more problems in the 1940s. After World War II he had an extended film career. In the remains of this film we see the great department stores but also the contrasting pictures of urban rubble where children play. And there is a torchlight procession of Nazi Storm Troopers.

Kurzfilme 2: Experimente mit Ton und Farbe (Short Film 2: Experiments in Sound and Colour) offered nine film made between 1922 and 1934, the majority from the early 1930s. They consisted of actuality film, advertising film, puppet animation and conscious experimentation. All of them used varied colouring techniques for the period. Staff from the Deutsche Kinemathek introduced the programme providing illuminating detail on the various colour formats used. This selection was screened from 16mm and 35mm prints and DCPs.

Der Sieger (The Victor, 1922) and Das Wunder (The Miracle, 1922) used hand colouring and tinting processes, techniques that had appeared in the earliest days of the new medium.

Farmfilmversuche, Demo-Film für Sirius Farbverfahren (Colour Tests, 1929) used a Dutch subtractive two colour system. In the earlier experimentations in colour systems relied on two rather than three primary colours. This produced acceptable results and could utilise the two sides of the film print.

Wasserfreuden im Tierpark (The Joy of Water at the Zoo, 1931) relied on Ufacolor. This was another subtractive two-colour system introduced in 1931 by Germany’s major production company.

Palmenzauber (Palm Magic, 1933/1934) was an advertisement using Ufacolor.

Zwei Farben (Two Colours, 1933) was a more experimental advertisement using Ufacolor. It made great use of the two primary colours in the system, red and blue.

Alle Kreise Erfasst Tolirag (Tolirag Circles, 1933/1934) was an experimental work by Oskar Fischinger, a major cinematic artist in this period. Gasparcolor was a subtractive three -colour system, the technical advance that made Technicolor a dominant system for several decades. It was developed by a Hungarian scientist. Fischinger used it in several of his works in the period and at least one Len Lye animation also used the system. The palette was different from Technicolor but it looked really fine.

Pitsch und Patsch (Pitter and Patter,1932) was a drawing-based animation. In a distinctive set of techniques the sound was created by wave-like drawings that produced an equivalent of the soundtrack patterns printed on film stock.

Bacarolle (1932) used the same techniques but married with puppet animation.

This was a fascinating programme and I had great pleasure in watching the different colour palette and imagery. The different films came partly on 35mm film and partly on DCPs. Günter Buchwald provided accompaniment for the non-sound films.

The screenings were provided in two cinemas out of the many involved in the Berlinale. The CinemaxX is a multi-screen venue: one of a the many sited around the central space of the Festival, Potsdamer Platz. Screen 8 is the auditorium that can project both 35mm and D-Cinema. It seats around 250, has a fine rake and proper masking for the screen. I was devised [correctly] that the front three rows are vary close to the screen. For the retrospective a piano had been provided and bring-in eats and drinks banned.

The other venue is Zeughauskino sited just off the Unter den Linden. This is set among in an area of museums and cultural venues. It is a multi-purpose auditorium but well suited for cinema. It has 16mm,35mm and digital projection. The seating is good as are the sight-lines. And the screen has proper masking. It has a good quality piano and I thought the acoustics for live music slightly superior to CinemaxX.

The projection standards were good. We had a variety of 35mm prints and DCPs, several at 4K. The prints, with the exception of one dupe, were good. And I thought the digital transfers were of a good standard. Quite a lot of the sub-titles in English were digital projections but they looked fine.

The Light of Asia was the only film that I gave up on in the programme. I thought that the live musical accompaniments were well done. The four musicians were Günter Buchwald, Stephen Horne, Maud Nelissen and Richard Siedhoff. The first three are regulars at Festival such as Il Cinema Ritrovato or Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. The are experienced and accomplished accompanist. Richard Siedhoff was a [for me][ a new voice and he is a promising talent.

The programme was popular,. There were always queues beforehand and a number of screenings were fully sold out. The audiences were pretty well behaved. There were few distractions form mobile phone rings; and I only saw one person taking still during a feature. We did get a number of people checking the time on their phones: a really annoying and unnecessary habit. But generally they were absorbed in the films and warms in their appreciation. This also applied to the final Sunday, ‘People’s Day’ / ‘Publikumstag’. Now ordinary Berliners (not just the film buffs) can check out the varied programmes and films. The last day and the final screening heard warm applause for the staff who had shepherded us through the ten days of the Festival. With almost stereotypical German efficiency it was really well organised.

One of the staff with Deutsche Kinemathek told me that they had checked about 200 films in choosing the programme. There is clearly scope for Weimar retrospective II which would definitely find me in Berlin again.

Quotations from Weimarer Kino neu gesehen Brochure.