This French silent was screened at the 2008 Il Giornate del Cinema Muto. It is both a romance and a political satire. I not only enjoyed the film but also started noticing interesting parallels with a later British sound film, Fame is the Spur. The discussion of the two films that follows does include plot spoilers.

LES NOUVEAUX MESSIEURS (Translated as The New Men) Films Albatros/Sequana Films, France 1928.

Director: Jacques Feyder; screenplay: Jacques Feyder, Charles Spaak, from the play by Robert de Flers & Francis de Croisset (1926); photography: Georges Périnal, Maurice Desfassiaux; design: Lazare Meerson; cast: Albert Préjean (Jacques Gaillac), Gaby Morlay (Suzanne Verrier), Henry Roussell (Comte de Montoire-Grandpré).

Filmed: 27.628.9.1928 (Brie-Comte-Robert; Créteil; Brunoy; Château de Bisy; Studios Billancourt).

35mm, 2805 m., 123′ (20 fps); print source: Cinémathèque Française, Paris.

French intertitles [with a translation].

Musical score composed and conducted by Antonio Coppola, performed by I’Octuor de France.

“Les Nouveaux Messieurs, by Francis de Croisset and Robert de Flers, had been the hit of the 1925-26 Boulevard season, enjoying a run of 400 performances. It was a romantic and satiric comedy that described a tug-of-war waged over a pretty young actress by two men: her ageing aristocratic protector and a young left-wing electrician union organiser. The aristocrat uses his wealth and connections to protect his protégéé, but the worker wins her over with his casual charm and dynamic self-confidence. The electrician is appointed labour minister in a new left-wing government, only to lose his position (and lover) when the government is toppled.”

Lenny Borger in the Catalogue 2009.

The play from which the film originated was first performed in 1926. It would seem likely that it was commenting on current political developments in France. There was a General Election in 1924. It was narrowly won by the Cartel des Gauches, which replaced a conservative government. The Cartel was an alliance of radicals and socialists, with a small group of communist. However, the new government was undermined by disagreements among its members. What finally bought it down were economic forces. There was a large deficit in the French budget, exacerbated when the reparations awarded to France from Germany at the Treaty of Versailles were postponed by the US sponsored Dawes Plan. Unable to resolve the crisis the Cartel lost the support of centrist groups, and was replaced by a government of National Unity. The Cartel leader Herriot joined in, but it was really a conservative administration.

[See A History of Modern France, Volume 3: 1871 – 1962, Alfred Cobban. Pelican].

This French silent provides an interesting contrast with the later sound film made in Britain, Fame is the Spur, UK Two Cities 1947, black and white, 116 minutes.

Produced by John Boulting. Directed by Roy Boulting. Script by Nigel Balchin from the novel by Howard Spring.

Cast: Hamer Radshaw – Michael Redgrave. Ann – Rosamund Johns. Tom Hannaway – Bernard Miles. Arnold Ryerson – Hugh Burden. Lady Lettice –

Howard Spring started out as a journalist in South Wales, and then moved on to the London Evening Standard. This, his most well known novel was published in 1940. It is a salutary tale [the leading character appears to be modelled on Ramsay MacDonald] of a working class lad who succeeds in becoming a Member of Parliament, a Government Minister and finally a Lord: but loses touch with his roots and his class politics. The novel begins with a quotation from John Milton’s Lycidas:

“Fame is the spur that the clear spirit doth raise

(That last infirmity of noble mind)

To scorn delights and live laborious days.”

The film broadly follows the book and opens with this quotation in a voice-over by the lead actor. It provides an apt comment both on this British political saga and the earlier French farce. The narrative is organised around episodes, usually introduced by a title showing the year, running from 1870 to 1937. The French and British films are in many ways very different, including one being silent and one sound. But there are also interesting parallels in the character situations and the development of the plot.

Like Nouveaux Messieurs, Fame is the Spur is loosely based on actual events and characters. And the latter film mirrors the earlier one in that a key moment in the narrative is an economic crisis that impacts on the governing class. In Fame is the Spur Hamer has become the Minister for Interior Affairs in a Labour Government. The Wall Street Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression lead to the formation of the National Government led by Ramsay MacDonald. Hamer joins this collaborationist government, which [among other measures] institutes a cut in unemployment benefit.

Hamer ‘sells out’, as indeed does Gaillac.

In fact this crossing over of the class divide had becomes increasingly clear as Hamer’s career progresses. Like Gaillac he acquires the external trapping of the bourgeois politician, the top hat and evening dress. He also acquires a large and expensive mansion. In Nouveaux Messieurs Gaillac visits a new housing estate dressed in his top hat and tails, demonstrating his alienation from the working class party supporters. In the British film at one point we see Hamer vainly attempting to persuade Welsh miners to support the Imperialist war effort. This contrasts with his early working class family and upbringing.

Hamer stirs the miners with his grandfather's sword

In Nouveaux Messieurs we see Gaillac at the C.I.T. offices with a copy of Karl Marx’s Capital on his desk. [C.I.T. is presumably meant to strand in for the actual C.G.T. Confédération Générale du Travail]. The equivalent scene in Fame is the Spur shows Hamer in an early job in a Manchester Bookshop. Among the photographs on the wall is a portrait of Karl Marx. Hammer’s young female admirer, Ann [whom he later marries] comes to be ‘instructed’ and he lends her An Introduction to Capital.

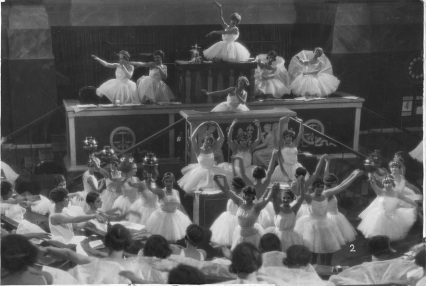

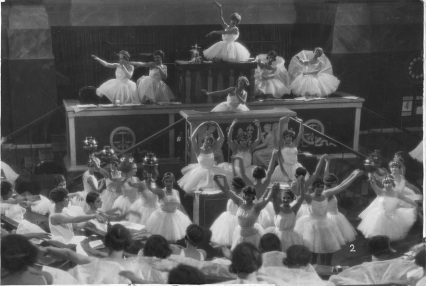

Some of the parallels are rather different in presentation. So in Nouveaux Messieurs we see a French deputy dreaming in the chamber: of nubile ballet dancers pirouetting in the aisles. In the Boulting film the ‘dream’ sequence refers to the tale told to the young Hamer by his granddad. This is a reminiscence of the Peterloo massacre in Manchester in 1819. This is not a realistic flashback, but an imagined event [presumably by Hamer] where the workers wear garlands of flowers and the attacking yeomanry are dressed as medieval knights. The grandfather has retained a souvenir from this infamous event, a yeoman’s sword, which becomes a symbol of Hamer’s youthful radicalism.

Fame is the Spur uses frequent montages: i.e. rapid sequence of shots highlighting events, as for example in the St Swithun Parliamentary election where Hamer cuts his political teeth, or when the Suffragette agitation is introduced. Nouveaux Messieurs uses a rather different technique, rapid accelerated motion, during the tour by Jacques of the new housing estate, as he desperately tries to rush back to the political crisis in Paris.

There are two important developments in the plot where the films differ considerably. In Nouveaux Messieurs Suzanne accompanies Jacques when he goes to address a transport workers strike. Jacques is successful in halting the march by the workers; and later, at a rally, suggests the speeches are ended and that there be dancing. The strikers win concessions, but Jacques is clearly restraining worker’s militancy in a reformist manner.

In the Boulting film Hamer’s equivalent scenes is when he goes to address striking Welsh miners at the request of his friend Arnold. Hamer stirs the miners up to a militant pitch, brandishing the sword from Peterloo as a symbol of class resistance. In the ensuing fracas a worker is killed and Hamer is seen as an agitator, though he vigorously disclaims responsibility.

Even more interesting is the comparison between the heroines of the two films. Suzanne is a fairly active heroine, but the plot contains her as an object of male interest. By the end of the film she has opted for the affluent life provided by the Comte and is still a ballet dancer at the prestigious Opéra; a position first obtained for her by the Comte and then reinstated by Gaillac as a Minister. Ann, in Fame is the Spur, is equally subservient to Hamer early in the film. But by 1912 she has become a militant supporter of the Suffragette movement. Hamer, now well down the path of reformism, opposes the movement and votes for women. In fairly harrowing scenes the audience see Ann in Holloway prison and enduring the violence of forcible feeding. This exacerbates her consumption and she soon dies: leaving Hamer to the admiration of his aristocratic admirer, Lady Lettice, [wife of the Earl whom Hamer opposed in the earlier St Swithun’s election].

Fame is the Spur received an A Certificate and did not suffer the fate of Nouveaux Messieurs, which was banned for a time and then suffered enforced cuts to the film. This was presumably down to the more radical climate in the 1940s Britain with the mood of ‘no return to the thirties’. And the French film appeared after a further General Election in France in 1928. This was won by the conservatives, and presumably sharpened the satire of Nouveaux Messieurs for audiences.

With everything going for it, nobody was ready for the shock awaiting the finished film at a first trade screening in late November 1928: it was refused a distribution visa and subsequently banned! The parliamentary world was up in arms: the film was declared an act of lèse-government, and a number of MPs, among them the president of the Chamber of Deputies, claimed to recognise themselves in some of the more unflattering portraits. Both Left and Right felt they were on the receiving end of Feyder’s satiric darts.

The scandal swelled ludicrously, only to subside months later. The distribution visa was finally delivered – pending cuts (the unkindest being the now-lost ironic epilogue at the train station, where the aristocrat sees his ex-rival off to a safely distant post in Geneva: “Vive la Republique!” yells the worker; “Vive la France!” the anti-parliamentarian counters).

Lenny Borger

The farewell

Fame is the Spur has a very different sort of ending. The Boulting brothers came up with an inspired scene, which is not in the original novel. Now 75 and a Lord, Hamer returns to his mansion and overcome by memories takes down the sword from the mantelshelf and tries to draw it from the scabbard. He fails; it has rusted up from disuse. A powerful visual symbol for the situation of Hamer.

Nouveaux Messieurs is essentially a farce, whilst Fame is the Spur is a melodrama with tragic overtones This would seem to reverse Marx’s dictum, ‘that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce’. But the films also fit with stereotypical representations of the differences between French and British culture. The French film is a satirical farce, and at the centre is effectively a ménage à trois. The British film is clearly a melodrama, which opts for a serious moral stance rather than satire or even irony.

The Director of Nouveaux Messieurs, Jacques Feyder, was an established filmmaker by 1929. In the 1920s he directed a number of fine features that are seen as early examples of French Poetic realism. [One example would be Crainquebille (1922) screened at an earlier Giornate]. But he had a chequered career. In 1929 he went to Hollywood for a period, but was not successful there. He had already demonstrated a clear touch for comedy and satire and his most famous film, La Kermesse heroique (Carnival in Flanders, 1935), is a satire on war set in a C17th village occupied by Spanish soldiers. Like Nouveaux Messieurs, the film mixes political and sexual conflicts in its plot.

The Boulting Brothers are now probably best remembered for their 1950s comedy. This included I’m Alright Jack, a satire on industrial relations that caricatured both bosses and workers. However, in the 1940s the Boulting were young and radical, part of that post-war left-leaning generation. Their earlier Pastor Hall (1940) was a savage indictment of the Nazi, and even ventured into the violent world of the concentration camp. And The Guinea Pig (1948) followed a working class lad [Richard Attenborough] trying to make a success of a scholarship to a Public School.

So the two films provide both parallels and contrasts. Given that the topic of parliamentary and class conflicts are not common in popular film, both their similarities and their differences provide an intriguing study.

Thanks to Il Giornate del Cinema Muto for stills from Nouveaux Messieurs.