This cycle of films was part of the programme at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2017 devoted to the silent films of John Stahl. In fact his name appeared nowhere in the credits which recorded one Benjamin Chapin as writer, director and star.

“at the time of its release it was completely identified with Benjamin Chapin, a noted theatrical impersonator of Abraham Lincoln. …” (Richard Koszarski in the Festival Catalogue).

Whilst Chapin was planning his cycle through his own Charter Features Corp. D. W. Griffin’s ‘The Birth of a Nation’ 1915 transformed the subject of the US Civil War and of Lincoln into major box office potential.

“Charter’s response was to advertise for additional technical staff, including “a Director of the most pronounced ability” to supplement Chapin’s existing unit. This seems to have been the moment Stahl came aboard, although Charter’s publicity arm, designed to focus all attention on Chapin, never admitted the fact.” (Festival Catalogue).

John Stahl, who entered the young film industry as an actor, had already directed one film, now lost, but uncredited. After this series he went on to direct nineteen features with credits as director.

Chapin had ambitious plans for the cycle.

“a sequential narrative whose structural complexity, he said, was modeled on Wagner’s ‘Ring Cycle’. The series of stand-alone subjects would not be linked chronologically like a serial, but thematically with all the episodes designed to address one central question: if Abraham Lincoln was America’s greatest president, what experiences acted to shape the development of his social, ethical, and political character.” (Festival Catalogue).

The cycle certainly did not match Wagner’s epic work. And Chapin did not emulate the long and arduous dedication to the work exhibited by Wagner, he was taken ill and died in 1918. But the cycle was already incomplete and unfinished and Chapin sold ten episodes to Paramount in 1917, who distributed them under the overall title The Son of Democracy. There was a reissue in the 1920s for the Education Market; apparently some packages had ten episodes, one eight and some titles were available individually. There are now two lost episodes with only eight surviving.

These were two reel films digitised and projected from a DCP, retaining the tinting of the originals. We watched them in the order that they had been distributed though they may have been filmed and completed in a different order in 1915 and 1916. The missing episodes were the eighth and ninth of the original ten part cycle.

We started with two episodes which are part of ‘My Boyhood’; both run running just on 25 minutes and accompanied by John Sweeney at the piano.

My Mother.

The title opens with Lincoln by a river notebook in hand.

A Flashback returns us to 1809. At this point the family, his mother Nancy, father Tom, young Abe and his sister Sarah, move from Kentucky to Indiana. In their rough cabin we see the mother reading from the New Testament in the family bible, ‘love one another’. Then a flashback within a flashback shows us the courtship of Tom and Nancy. Nancy make her husband promise to study and become literate. In the main flashback it is clear that Tom has not mastered literacy. So Nancy teaches young Abe. The family text for reading is Bunyan’s ‘Pilgrims Progress’. But Nancy is taken ill and she dies,

“Dear ones, goodbye.”

The film clearly intends to show Lincoln’s mother as the key influence on the young Abe and offers an emphasis on biblical morals. Starting with this episode sets down a particular marker for the cycle.

My Father

This title commences in 1861 with the President elect saying goodbye to ‘old friends’.

As so often he recalls a tale from his youth, ‘40 years ago’. At home Abe annoys his father with his constant reading.

Sent outside Abe becomes embroiled in a fight over a rabbit with his regular opponent, Hank Carter. In a nice background touch as Abe and Huck fight over the rabbit a young black boy makes off with the trophy. Abe receives a beating for the fight and his father takes the precious Bunyan and stashes it in a tree stump. But Abe’s literacy enable him to prevent his farther signing a fraudulent contract with Huck’s father. This and the memory of Nancy, [seen in a superimposition] makes the father relent and he fetches to book from the stump. A title informs us that Abe and his father

“reach an understanding.”

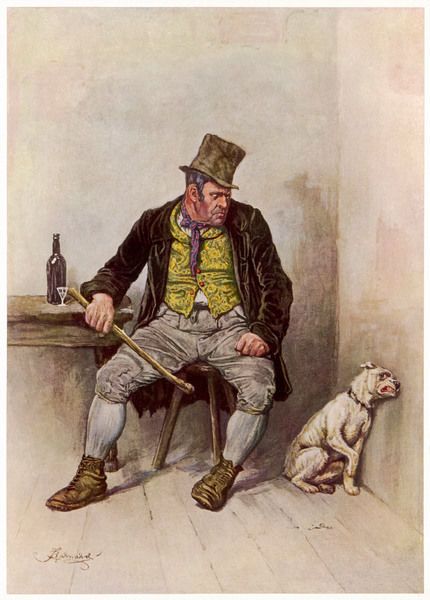

So this episode gives us the authoritarian father in contrast to the gentler and more educated mother. The Carters, junior and senior, are the regular villains of the piece. More affluent than the Lincoln’s, the son fights Abe whilst the father tries to exploit Tom and later a friend of Lincoln, Reverend Elkins.

The Call to Arms.

This episode ran 26 minutes and was accompanied at the piano by Gabriel Thibaudeau.

This episode opens in 1861 at the White House with his two sons, Willie and Ted who are scolded by their mother for being in wet clothes after bathing. Abe remarks,

“That reminds me.”

We see a brief flashback to one of Abe’s fights with another boy, Huck, He is reprimanded by his mother who raises the bible.

Lincoln now receives a delegation as the crisis with the Southern States mounts.

There is another brief flashback to Abe and his dying mother with his promise ‘never to fight’.

Back to 1861 and the South fires on fort Sumter.

“Union dissolved.” “Seven stars lost to the flag.”

A further flashback to Lincoln making an election address, holding up the Stars and Stripes and making a promise,

“Not one star shall be lost.”

Back in the present the President reads the ‘call to arms’ and cheering crowds respond.

There is now, [the only example in the whole cycle] a sequence from 1917. This is a newsreel of a ‘Wake Up America’ demonstration with Chapin dressed as Lincoln urging on the demonstrators.

This episode has more flashbacks than is the norm in the cycle, including the ones involving his now dead mother. These symbolise Lincoln’s struggle with the necessity of waging war.

The last sequence, effectively a flash-forward plays into the debate in the USA about involvement in the war taking place predominantly in Europe.

Then we had two episodes in a screening with Gunter Buchwald playing accompaniment at the piano.

My First Jury

It opens in the White House where Lincoln has to decide on an appointment in his Gentryville; the part of Illinois where the Lincoln’s lived for a time. The appointment is to the Post Office and the candidate is Billy Jinks. In Gentryville we see blacksmith Huck Carter [his childhood opponent as an adult] ‘cussing Lincoln’. Denver Hanks, who I think is from Lincoln’s mother’s family, writes to Lincoln recounting this. The letter motivates another flashback.

We now see a flashback to the young Abe. He and Huck regularly have fights.

On this occasion a young black boy, Jim, is chased accused of stealing a chicken belonging to the Carters. Abe proposes a trial; Huck is prosecutor and Abe defender. The jury consists of a cat, a donkey and a goat. Predictably Jim is found not guilty’. This provoke another fight between Abe and Huck whilst Jim escapes with the chicken, though he soon loses this.

In the present Abe writes back to Denver who reminds Huck of a piece of evidence, a sickle, still hanging in a tree from the earlier time.

Tender Memories

Running nearly 29 minutes.

The Civil War is under way and the White House is besieged with petitioners . Lincoln visits the front line. Here a skirmish occurs and two Union soldiers are shot. Lincoln comes on a soldier praying at a rough cross/grave. The scene is set at night-time and the fire and flares have red tints. Lincoln reassures a young soldier and tells him a tale.

A flashback takes us back to when Abe lost his mother. She is ‘laid to rest’ in the woods and Tom, Abe and Rash put up

“a rude cross”.

Then Abe writes to the Reverend Elkins to come and pray over his mother’s grave. This is delayed as the Reverend arrived during the fight between Abe and Huck and the minister left the scene. Later Abe is able to explain the fight and convince Elkins to pray at the grave.

At the end the soldier salutes Lincoln.

A further flashback expands on Abe’s letter. We see the family with the Reverend at the grave as all kneel and pray. Abe seems to see his mother, a superimposition..

She died in 1818 and the last shot is the grave

”grave as it is today”

with two children kneeling there.

Another double bill was accompanied at the piano by Donald Sosin.

A President’s Answer.

Running 24 minutes.

This opens with the White house which was the

‘same in Lincoln’s day” and filmed with “special permission.”

Now we encounter Huck again; now a Confederate agent recruiting for their army.

One of his targets is the son of Reverend Elkins and his wife David. Lincoln and an officer come across David, now a prisoner of the Union. In Gentryville Elkins reads of David’s capture as a ‘traitor’.

Selling his house he comes to plead his case in Washington. Edward Stanton, the secretary of war, argues against

“setting aside verdicts.”

Elkins visit his son and encounters Lincoln in the garden.

A flashback shows us Abe and ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’, a present from the Parson. And we see his prayer over the grave of Abe’s mother.

Despite the argument of Stanton Lincoln releases David into the custody of his parents.

Native State.

Running just on 30 minutes.

This title opens in 1863 and secretary Stanton has decreed the confiscation of enemy property: including the home of supporters of the Confederacy in Washington. One of these is the grandson of Daniel Boone who is to be evicted. Out in his carriage with his son Lincoln passes the house where the now blind old man is sitting as the house is emptied. Lincoln sits on the bench beside the old man who swears

“vengeance on Lincoln.”

Lincoln writes a note to Stanton and we enter a flashback.

Lincoln’s grandfather Abraham has joined Daniel Boone in Kentucky where fighting goes on with hostile Indians. His father, then a young Tom, finds his sister Dot is missing. He finds her in the woods but both are captured by an Indian, Crow Eye. At the Indian camp there is debate as to what to do with the c children. Sympathetic Indian squaw, Fawn, takes the children away. The trio are menaced by a wild cat. But Abraham, searching for the c children with Boone, shoots the animal. Fawn is allowed to leave.

When the flashback ends Lincoln orders the Officer to leave and countermands the order of eviction. Informing Boone of this they shake hands and Lincoln leaves.

So the final surviving episode of the cycle, accompanied at the piano by Daan van den Durk.

Under the Stars

Running 27 minutes.

The stars in the title refer to the flag; the issue, discussed at a White House cabinet meeting, is whether Kentucky, a slave state, will join the Confederacy. There are cuts between a series of scenes: the cabinet discussion: the meeting of the Kentucky State caucus: Lincoln playing with his son in the White House garden: and Lincoln with Colonel Homes, an emissary from Kentucky.

So that “Kentucky is saved for the flag” Lincoln sends a letter to the Kentucky leaders recounting another of his tales from the past.

In a flashback we again encounter the Lincoln family in the times of the grandfather Abraham. The family move from Virginia to Kentucky. They set up in a cabin near a fort where is seen Daniel Boone.

After a dispute over a dead deer ‘hostile ‘Indians’ attack the cabin. Then Abraham is killed by an arrow in the back. A rescue party from the fort, including Daniel Boone, find the young Tom by the body of Abraham.

In the present Lincoln concludes

“[He] gave his life to place the star of Kentucky in the flag.”

The title ends with the Kentucky State Assembly approving neutrality in the war.

Richard Koszarski, in his article in ‘The Call of the Heart – John M. Stahl and Hollywood Melodrama’ (2018) has brief plot outlines for the missing episodes.

‘Down the River’

The Mississippi in the olden days was infested by bands of slave-dealers who seized free negroes and sold them into slavery. While floating with the tide down the river on a long raft with a load of goods, young Lincoln becomes the central character in a contest of craftiness and violence with the worst of these gangs who have stolen a free negro from New Salem, a little black urchin, cause much excitement and furnish the side-splitting fun of this picturesque romance of the Mississippi.

“Ninth Chapter ‘The Slave Auction’

This shows the slave center at its worst. Here young Abe is at close quarters with the band of slave-stealers. To save the free negroes, he again becomes the main figure of a drama of plot and counterplot, suspense, excitement and humor in their highest form. In the very shadow of the auction block a voodoo fortune-teller prophesies that he will become President, that he will be the leader in a great war and that through him will slaves be freed. Lincoln fails to save the free negroes and in righteous wrath he vows,

“I I ever get a chance to hit slavery, I’ll hit it hard.”

Both the voodoo woman’s vision, and young Abe’s pledge come true, for, in thirty-one years, Lincoln, as President, signs Emancipation Proclamation, abolishing slavery for ever.”

These synopsis are marketing material and do not really offer a sense of the treatment. Does either episode use flashbacks in the manner of other episodes? In fact they seem connected in a linear story that is different from the rest of the cycle. It is not clear if the mini-narrative consciously illustrates from Lincoln’s experience; is he recalling events in some situation. The resolution of ‘The Slave Auction’ does suggest the events recounted offer an explanation of a central part of Lincoln’s project. It is also intriguing; why are these two episodes missing? I have not seen any explanation of this. It seems that they were omitted in some releases of the Education version in the 1920s. If so it suggests a value-laden decision. The Hollywood studios were prone to omit material on the ‘Jim Crow’ culture of the South and its antecedents because of fears of effects on box office.

Noting that reservation the surviving overall cycle remains an impressive work. It would seem that Chapin is important in the development of the project. However, it is also clear that Chapin deny proper credits to his collaborators and critics have to surmise their input.

Richard Koszarski, in the Festival Catalogue, has provided some of the cast and craftspeople involved. Chapin played Lincoln, his father Tom and his grandfather Abraham. Lincoln as a boy – Charlie Jackson. Nancy Hanks, the mother, Madelyn Clare. Other cast members included Alice Inwood, Florence Short, Joseph Monahan and John Stafford. These names were revealed by Stahl when he publicised his own role as director.

There seem to have been a number of writers who contributed to the screenplays: Paul Bern, Monte Katterjohn, William B. Laub and Donald Buchanan. There were at least three cinematographers who worked on the cycle: J. Roy Hunt, Harry Fischbeck and Walter Blakely. The production was filmed in 19125 and 1916 on the East Coast Studio. Visually the film is conventional relying mainly on mid-shots and long shots. There are frequent use of the iris to focus on a character, prop or detail. The editing is excellent, though not credited. The entrance and exit to the flashbacks is well judged and produce a fairly complex narrative for the period.

It is difficult now to determine whose influence produced what in the cycle. Chapin clearly bought an overall vision to the series of films. Richard Koszarski makes some comments on the possible contributions of both Chapin and Stahl.

“Many events depicted do not recall any of Chapin’s theatrical productions, especially the emphasis on young Abe’s relationship with his mother in the first episode, or the continuing concern with slavery and racial injustice seen in My First Jury, Down the River and the Slave Auction … last two episodes unfortunately missing) … [it] focuses instead on his [Lincoln] sense of patriotism and justice and refers to the rebels as traitors, an unusually blunt position noted with surprise by reviewers.”

The synopses for the missing episodes suggest a different treatment in My First Jury from the two later films. And the emphasis on patriotism may well have been because of contemporary issues, including that of war, where Chapin takes a pro-entry position. And perhaps the blunt condemnation of the Confederacy, like the issue of slavery, was a factor in the missing episodes being excluded.

On the narratives Koszarski writes:

“Even more striking is the way in which the Cycle uses memory. The film incorporates flashbacks as a basic structuring device illustrating how formative experiences shape our entire character …..”

He notes how some instances, such as the fights with Huck Carter, are presented more than once and with different footage. And he also raises the way character is presented; the importance Nancy, Lincoln’s mother. He wonders regarding the issue of slavery, noting that this is an issue [like motherhood] which is not found in the theatrical productions by Chapin that proceeded the films.

One can also speculate about what was bought to the series by the team of writers used by Chapin. Paul Bern was a noted, writer, director and producer whose credit includes the memorable Grand Hotel (1932). Monte Katterjohn was an experienced film script writer hose most famous credit is the 1921 The Sheikh. William B. Laub was another writer, here at the start of his career. A number of his credit are period dramas. Donald Buchanan was similar, starting out writing stories for films and progressing to script writing.

Like the surviving reels the queries on authorship are more questions than answers. But the production teams produced a fascinating exploration of Lincoln and his position in US culture. This was the period that followed the elevation of Lincoln to his status as the greatest US President. Chapin’s career, on stage, on film and as a public figure testify to the centrality of the figure to the US history. Following the cycle through the week of Le Giornate was a rewarding experience.

Note, the version at Le Giornate was transferred from the prints held at the Packard Center of the Library of Congress. There were safety prints from the Education Version. Thank you to Zoran Sinobad for the information,.