Kennington Bioscope on line on You Tube

[Note, the first 50 seconds are a blank screen with no sound then the opening credits appear.]

May 5th is one hundred years since the death of this British film inventor and pioneer. The Kennington Bioscope is streaming a discussion on his life and work by three researcher/historians; Ian Christie: Peter Domankiewicz: Stephen Herbert; ‘Back in focus: The Centenary of William Friese-Greene’.

Friese-Greene was one of a number of people in the 1880s experimenting on techniques to produce the illusion of a moving image from projected photographic film. He produced several working cameras between 1888 and 1891 and issued a patent for these. However, like some of the other inventor, he was not successful in projecting these images in a public showing; it was the Lumière Brothers success in this that made their work historic.

Friese-Greene ran a successful photographic portrait studio but his main interests were his experiments and the costs of his work on moving images led to bankruptcy. In the early 1900 he then experimented with early colour film. One of these, Biocolour, was projected successfully but it was eclipsed by other examples; it suffered from heavy flicker and colour fringing. Examples of his early films are available on You Tube, including a refurbished version of ‘The Open Road’, shot by his son Claude using his father’s system.

Friese-Greene‘s last public appearance was attending and speaking at a meeting of members of the British Film industry. Ironically he collapsed at the meeting and died.

He was for a long time a forgotten figure. The film biopic,The Magic Box, produced in 1951 was planned to accompany the Festival of Britain in that year.The film was produced by Festival Film Productions, partly funded by the National Film Finance Corporation with contributions from all the major British production companies either for free or at cost. The script was by Eric Ambler based on a book by Ray Allister and directed by John Boulting. The film was shot in Technicolor, at that time reserved for prestige production in Britain. The technical side and the casting benefited from the varied contributing companies. There is is excellent colour cinematography by Jack Cardiff, fine production design by John Bryan and excellent costume design by Julia Squire.

The cast list is immense, with dozens of cameos from successful British film actors. In fact, it is possibly easier to spot who is missing than list all those who appear.

Despite or possible because of this approach the film was a failure. The film has an odd script and despite a fine performance by Robert Donat as Friese-Greene the film lacks dramatic development. The opening credits appear over a stone slab successive names of an interesting selection of film pioneers:

Thomas Alva Edison – whose employee W. K. Dickson developed a working camera.

Etienne Jules Marey – a French pioneer who developed a photographic ‘gun’ taking multiple images.

Louis le Prince – a French pioneer working in Leeds who developed a camera and possibly a projector

Louis Lumière ave son frère. – the famous organisers of a public projection in December 1895

And then Friese-Greene himself is inscribed on the slab for the closing credits; as with his grave which offers ‘the inventor of kinematography’.

The film’s script is structured around two flashbacks. At the opening we see Friese-Greene, on his way to a meeting of the British Film industry at The Connaught Rooms in London, visiting his second wife, now separated.. The visits motivates a flashback by his wife. She remembers the evening of their first meeting, following a visit to an early fairground cinématographe projection featuring Lumiére titles. Then, with friends, she is taken to Friese-Greene workshop where he demonstrates his early work exploring colour film. Most of the flashback concerns the travail of the family as Friese-Greene encounters increasing problems of debt.

After the first flashback see Friese-Greene arrive at the Industry meetings. A phrase by a speaker motivates a longer flashback. Friese-Greene remembers his courtship of his first wife and his early career in a photographic portrait studio.

His growing interest in the possibility of projecting moving images involves increased experimental work but also an increasing debt burden. Much of this concerns his work with the newly developed celluloid, a crucial technology for film projection. In an undated sequence we see him successfully project moving images; at about ten frames a second with a pronounced flicker. He rushes into the street and finds a policeman to whom he can demonstrate his invention; a cameo by Lawrence Olivier.

We then see the affect of his debt and bankruptcy on his family; his wife died young. But the projection sequence appears as a climax of the flashback. We return to the meeting where Friese-Greene makes an impassioned plea to the uncomprehending meeting. Shortly afterwards he collapses and dies.

The film’s focus is the travails of his career. The sequences showing his experiments are brief. That depicting colour does not give much sense of the technology but that showing his working camera and projector does give a greater sense of its operation. There are some dates, such as the Industry meeting, but others, like the success with projecting his film,or his work on colour film, is curiously undated.

Brian Coe in ‘The History of Movie Photography’ (Eastview Editions, 1981) is sceptical of the claims put forward in the film. He questions whether the machine described in Friese-Greene’s patents actually projected at the required frame rate of 16; and he reckons that the inventor only used celluloid after its use in the Edison workshops. Friese-Greene’s Biocolour system has more credence but fell foul of a patent suit by Charles Urban for his Kinemacolor.

Michael Chanan in ‘The Dream that Kicks The Prehistory and Early years of Cinema in Britain’ (1980) has several pages on Friese-Greene in his chapters on patents. He writes that the inventor probably did develop some form of celluloid which he used in his 1889 camera. Chanan also notes that the patent is jointly in the name of Friese-Greene and an engineer Mortimer Evans. However the frame rate of around ten per second would not have produced a viewable moving image.

There is more on Peter Domankiewicz’s Blog ‘William Friese-Greene & me’. Happily it also includes posts on another pioneer in Britain, Louis le Prince. The Bioscope presentation will likely shed more light on Friese-Greene and his contribution to cinema history.

The KB seminar addressed both Friese-Greene’s biography, his technical achievements and the ups and downs of his reputation. It was introduced by Nicholas Hiley, a trustee of the Cinema Museum where the Bioscope is based. He noted that they were not able to show actual clips from The Magic Box as screening these on You Tube would be a breach of copyright. There is a real irony in this. Friese-Greene’s financial problems stemmed in part from legal disputes over patents. Copyright is a form of patent and after dying in poverty Friese-Greene’s work is now protected for profits be other capitalists. The irony was not remarked on.

The first presentation was by Peter Domankiewicz who is researching Friese-Greene’s life and work. He provided an overview of the inventor and addressed the ‘problem’; the two very different assessments of his achievements. Peter talked about his life, with illustrations, images of replicas of his cameras, and some digital versions of the film that he did make.

Running successful photographic studios Friese-Greene worked with a John Rudge in 1881; the latter having a lantern projector with a primitive shutter mechanism. By 1885 they had a four lens lantern which created a form of moving image. In 1889 Friese-Greene took out a patent for a single lens camera which ran at about ten frames per second and included pinholes on early celluloid as the film strip. This was earlier than the use of celluloid by Thomas Edison’s employee, W. K. Dickson. Friese-Greene went on to take out a patent for a stereoscopic camera and then for early colour film stock. But his cameras all seem to have operated about ten fps, slower than the minimum of 14 fps which produces the illusion of movement.

Peter did talk about the irony of the obscurity in which Friese-Greene lived at the time of his death which was then overturned and led to his funeral being a large public event and a continuing reputation as a key inventor in the development of what became cinema.

Steve Herbert talked about the technical aspects of Friese-Greeene’s inventions. Steve was involved in 2000 in the ‘race to cinema‘ project. Their website contains illustrations and information about the replicas, including two by Friese-Greene and also one by the Leeds-based inventor Louis le Prince. Steve presented some of these replicas in stills and short moving image sequences. He pointed out that the patents involved associate engineers; for the single lens camera Mortimer Evans. He commented on the frame rates of Friese-Greene’s camera, only 10 fps or less. And he made a general point about the early inventions that one lacunae was the absence of a sprocket system. This was the contribution of W. K. Dickson and the Lumiere Brothers, the latter developing a combined camera/ projector. Steve will be posting a fuller discussion of this issue on his webpage, The Optilogue.

Steve also recounted an odd little tale. For the production of The Magic Box replicas were made of both Friese-Greene’s monoscopic camera [single lens] and his stereoscopic camera [dual lens camera] but that the one used in the famous sequence where Robert Donat as Friese-Greene demonstrates his moving image to a Police Constable is the stereoscopic camera.

Steve concluded on the claim in Roy Allister 1948 book ‘Friese-Greene: close-up of an inventor’ , labeling him ‘the father of film’. But the mechanisms only reached 10 fps and were limited to cameras rather than projectors.

Ian Christie addressed the ‘afterlife of Friese-Greene; the ups and downs of his reputation. In the years after his death, at least in Britain, he enjoyed the status as a key inventor in the development of cinema. The Magic Box was the culmination of this viewpoint. In Britain the release of the film was seen as a major event; even though it did not do well at the box office. However, in the USA the film was described in one review as a ‘perversion of history’; the general view was that the British were inflating Friese-Greene’s importance.

Ian commented on how critical publications on the inventor undermined his status in Britain. Brian Coe, a prestigious critic because of his position at the Kodak’s George Eastman Museum, was damning in his comments. Michael Chanan offered a more balanced view. And John Barnes, author of ‘The Beginnings of Cinema in England, 1894 – 1901’, regarded Friese-Greene as having little relevance.

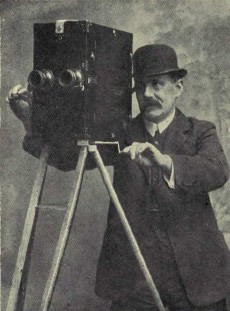

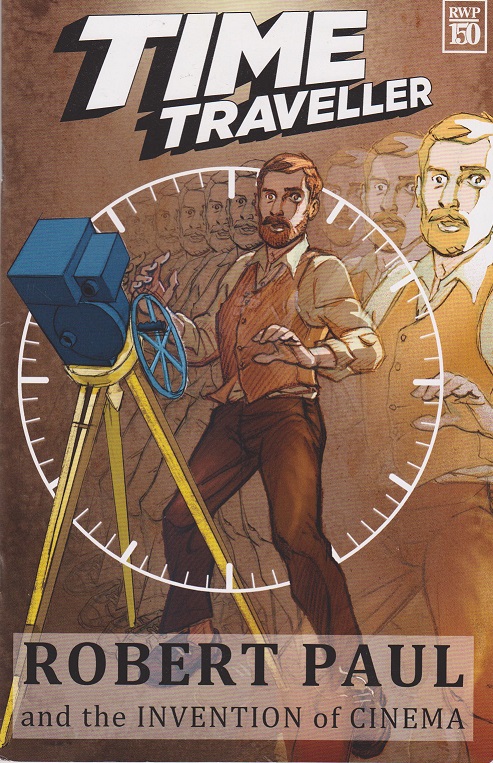

Ian also explained about a particular confusion in the film biopic. The famous sequence is where Donat, playing the inventor, demonstrates his camera/projector to a police constable. However, this conflates Friese-Greene’s work with an incident from the work of another British pioneer, R. W. Paul. Ian has written on Paul and the incident in question is illustrated in a graphic novel about Paul. He traced some of the mistaken writings that led to this confusion.

Ian ended with a quotation by Henry Hopwood in 1899;

“there never was an inventor of Living Pictures” (‘Living Pictures’).

This was a general view in which the three speakers concurred in the final Q&A with Nicholas Hiley. In times past there was an emphasis on the successful inventor/s who produced key technological developments. Nowadays there is a more general interest in the variety of contributions which led to a particular form of moving images.

Readers can check out the various sites indicated above and both Peter Domankiewicz and Steve Herbert will be adding more contributions to out understanding of Friese-Greene and the context in which he worked. And Ian Christie has published a major work on R. W. Paul, described on his web site.

Note; The Magic Box is a title that screens on ‘Talking Pictures’ [Freeview 81] and is on today, May 28th, at 6 p.m.