Screened at the 2019 Il Cinema Ritrovato, The Catalogue places this film in the programme of 1919; one of the titles already familiar to many in the audience.

“1919 was the year of the directorial debut of the man who was to become the greatest international name in Danish cinema. Carl Th. Dreyer had worked for Nordisk Films Kompagni for six years, first as a script consultant and writer of intertitles, then as a scriptwriter. He had worked on some 20 projects and had also tried his hand at editing.” (Dan Nisen).

After this apprenticeship Dreyer had many of the skills required to take up direction with this his first feature. Dreyer adapted the story from a novel by the Austrian writer Karl Emil Franzos. Nissen explains that,

“Dreyer had worked on the script and had cut away all the political and social material from the novel, which dealt quite a lot with class structure and the political situation in Austria.”

The former aspect means the film is predominantly a personal drama. I found the plotting rather more conventional than the later features by Dreyer. But the design, visualisation and performances are of the same recognisable quality.

“What interested Dreyer was the story of three men of different generations, failing to fulfil their responsibility toward women of a different class, bearing their children.”

The film opens with Karl Victor (Halvard Hoff) and his farther Victor von Sendlingen (Elith Pio). They are at the gates of a ruined castle, once the domain of the Sendlingen family. The father tells his son;

“I die a wretch.”

In a flashback he explains how his own father made him marry a r girl whom he had made pregnant.

“no good ever comes from such an alliance.”

and he makes his son swear never to marry a commoner.

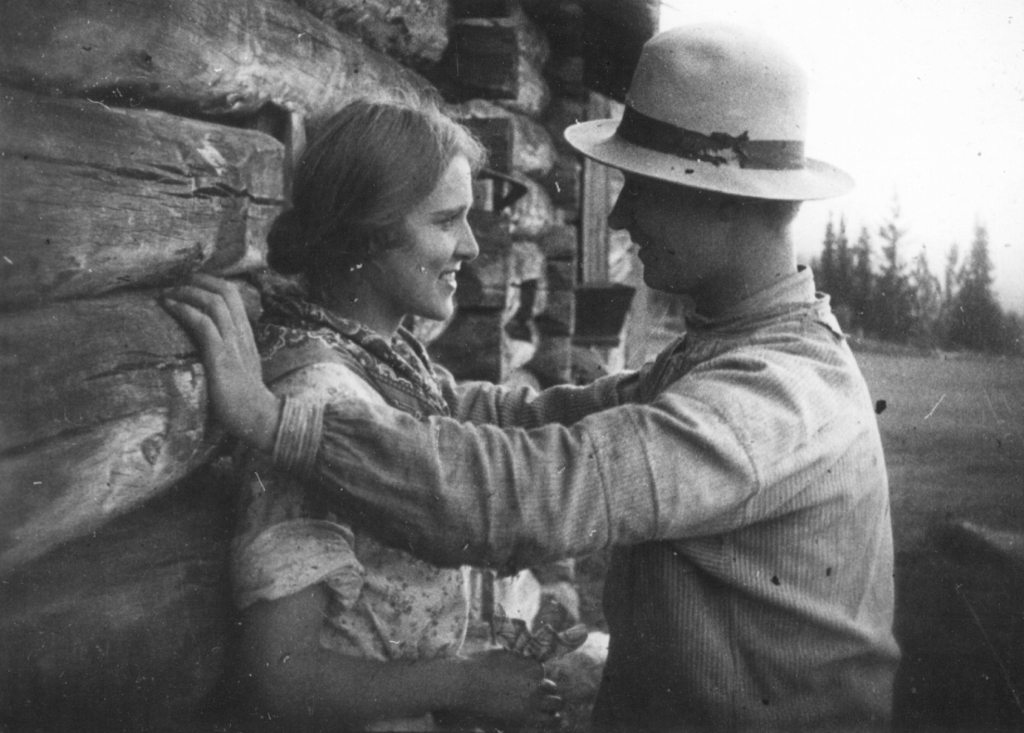

The films now moves forward three decades and Karl Victor is the President [senior judge] of the town tribunal. He is highly respected. This is demonstrated by a celebration I have never seen awarded a judge on film; the town people march in a torch lit procession to the unveiling of a bronze head of Karl Victor. His best friend is a lawyer, Berger. To Him Victor confesses that he cannot try an upcoming case because the accused is his illegitimate daughter, Victorine. He fathered her in a relationship with the governess of the children of his uncle. When he proposed to marry the pregnant young woman his uncle reminded him of the oath extracted by his father. Later, as a young woman, Victorine worked as a governess and was herself seduced by the young son of the family. She is now on trial because her baby died and she is accused of infanticide.

Berger unsuccessfully defends Victorine. Under sentence of death she is secretly released by Victor who flees the town with his daughter and two faithful servants. Three years later Berger comes across Victor, now under an assumed name.

Victorine is to be married. After the wedding Victor returns to his old t won and offers himself for trial. His successor refuses the offer on the grounds that it would undermine faith in the judiciary. Returning to the ruined family castle Victor jumps / falls to his death.

I have e not read the original novel but the plot presented by Dreyer is interesting among other ways in comparison with the film by Alfred Hitchcock from 1929, The Manxman. This film was adapted from a novel by Hall Caine. There are quite a few differences in the plot from the Dreyer work, but it shares the situation of a young woman on trial for infanticide and with the judge the man involved in her pregnancy and situation. The Hitchcock goes for the full-blooded melodrama of a confrontation in the court room. Dreyer, by contrast, adopts a far more restrained presentation, with the secretive escape. The Manxman’s sequence take place in the full light and public glare of the court room. The Dreyer has the quartet, surreptitious leaving by night, in scenes full of shadows and dark corners.

This seems to me to fit into the characteristics way that Dreyer treats people and their situations. He focuses on the way that people face the contradictions of life, often with an intensity rarely found d in cinema. Præsidenten is an early film and does not achieve the intensity of later works by Dreyer. I thought at times that the narrative was treated in rather conventional manner. In an early scene a young woman plays with a puppy and a kitten. This trope appears later in the film. And the mise en scene is often not as sparse as in later films. I did find that the opening and closing sequence at the ruined castle had the power that Dreyer develops as he grows more experienced.

The screening presented a restoration which had used newly discovered records of the tinting and toning for the film. This was a fine 35mm print and the tinting and ton tinting was very well done; avoiding the over-saturation that sometimes mars modern examples of the technique. And the film benefited from a fine and lyrical accompaniment by Gabriel Thibaudeau. The opening, as we encounter the ruin for the first time, struck a fine, plaintive tone.