The famous dictum by Jean-Luc Godard was voiced in the era of sound cinema; like much else in the cinematic discourse its applicability to the Silent Era needs to be questioned. Specifically, as well as using nitrate film stock, aspects ratios of around 1.33:1, and only additive colour, the ‘silent’ film screenings differed in the running speeds or frames per second from the sound film. The latter when it is actually film normally runs at 24 fps: a rate that as Kevin Brownlow points out was chosen by the technicians on the basis of the projection speeds at Warner first-run theatres. The films of the silent era ran at anything between 16 fps and 24 fps. Many 35mm projector have an adjustment mechanism, which enables the operator to change the projection speed: Photoplay Productions actually do this during the screenings for some films. One of the may oversights with the introduction of the Digital Cinema Package [DCP] was that the running speed, which is ‘baked’ into the digital folder as is the aspect ratio, only offered 24 fps and then in addition 48 fps. Now the La Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film [FIAF] have produced a series of specifications in The Digital Projection Guide for frame rates from 16 up until 24 [though only increasing by twos, i.e. 16, 18, and so on]. How soon projectors will be adapted or the producers of the folders will actually use different frame rates remains to be seen.

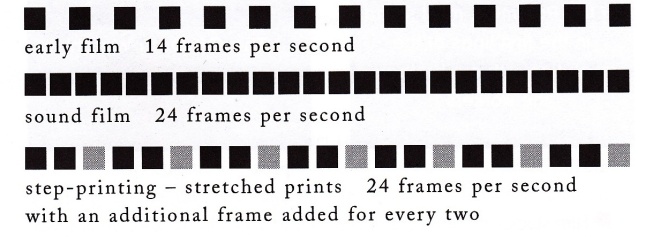

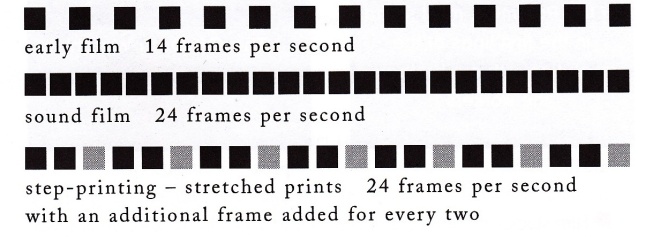

In what the UK Parliamentarians call ‘being economical with the truth’ digital publicity usually provides little information regarding the difference. It seems in most instances the producers add extra frames so that the film can run at the faster frame rate without producing the jerky, speeded up movement, which occurs if the film is projected at a faster speed. [There is also an associated technique ‘interlacing]. This is a technique known as ‘step-printing’: it has been used for decades, so that films originally shot at silent speeds were copied on to sound stock with the addition of extra frames. Quite often the assumption was that the original frame rate was 18 fps so there was an extra frame added for every three existing frames.

Computers have made the process more sophisticated: though the technique is basically the same, adding extra frames. However, one additional problem is that computers can add ‘composite frames’, frames that combine elements from the preceding and following frames into the new frame. Clearly this adds a new element in the film which was not put there by the original filmmakers.

The extent to which this alters the film or the viewing experience varies considerably. In my experience the effects are most noticeable when the transferred film uses fast editing and/or special effects. One example of the former is Sergei Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potemkin, USSR 1925). The most recent and complete restoration by the Deutsche Kinemathek dates from 2005. The British Film Institute released it for UK distribution in 2010 on a DCP. I had been fortunate enough to see the film at the 2010 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in a 35mm print. It was 1338 metres and ran for 70 minutes at 18 fps. The DCP from the BFI apparently was step printed by adding a frame to three to achieve 24 fps. And I noticed the effect, specifically when we arrived at the famous three lions following the Odessa Steps massacre. According to David Mayer’s ‘shot-by-shot presentation’ in Eisenstein’s Potemkin (1972, using the MOMA print), the sequence of these lions contains 162 individual frames in eleven shots. That would be nine seconds at 18 fps, and this would appear to be one sequence where the MOMA and Kinemathek prints would be identical. It is not clear how the extra frames are distributed across the separate shots. But in the DCP they seemed to ‘race past’ and the sequence as a whole seemed too fast.

I wondered what Eisenstein himself would have thought of this. The likely answer is to be found in Ivor Montagu’s With Eisenstein in Hollywood (1967). He records that after the screening of Potemkin at the London Film Society ‘He [Eisenstein] complained that, with the Meisel music, we had turned his picture into an opera”. The problem appears to have been that Meisel’s score was composed to accompany the German version, which had been censored. The Film Society used a print from the Soviet Union and Meisel told the projectionist to alter the film speed at some point so that the music synchronised. This may account for the laughter from some of the audience when the lions’ sequence was seen.

Another film, which suffered from step printing for digital release, was The Great White Silence (UK 1924). This is Herbert Ponting’s record of the ill-fated 1912 Antarctic expedition led by Captain Scott. Ponting filmed the early stages of the expedition and then used models to illustrate the later stages of the expedition from which Scot and his colleagues did not return. I saw the film at the 2011 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in a 35mm print. This was 2189 metres and ran 106 minutes at 18 fps. The DCP was presumably step-printed to accommodate 24 fps. And whilst the model shots on the 35 mm print were relatively convincing on the changed digital version they were somewhat anachronistic.

Hopefully these sorts of problems will be resolved when the FIAF recommendations are implemented. However, how long this will take and how effectively this will happen is unknown. The major projector manufacturers have provided appropriate software and hardware for conversions. But is would seem likely that teams transferring celluloid prints to digital will only use the frame rates when enough venues have converted. Rather worryingly there is not much sign of this happening yet.

Of even more concern is the increasing use of Blu-Ray and DVD’s for theatrical screenings, including when live accompaniment is provided. Presumably some of this is just down to cost cutting. DCP’s don’t have the delivery costs of 35mm prints. Blu-Ray and DVD are even cheaper to obtain and transport. Partly it also seems to be at the behest of musicians. I have been told on several occasions that the musicians accompany a screening preferred to use a videodisc because they had rehearsed to this. There was even a case at the Leeds International Film Festival there the orchestra wanted a 35mm print screened at 25 fps because they had rehearsed to that video copy. Having seen hundreds of live screenings graced by excellent musical accompaniment, ranging from solo pianos, through ensemble including singers, to large orchestras and choirs I have scant sympathy for this approach.

Blu-Ray and even more DVD do not offer the visual quality of DCP and certainly not of 35mm: though they may look OK when compared with old and worn prints. Frequently the aspect ratios are incorrect, and this cannot be corrected as in the case of 35mm projection. But most notably they are as fast or faster than 35mm sound projection: Blu-Ray running at 24 fps and DVD in the UK runs at 25 fps [elsewhere it can be up to 30 fps]. This means that almost invariably they use step printing to achieve the faster projection speed. Unfortunately distributors almost never seem to actually explain this. There is a dominant tendency to ‘being economical with the truth’ disguises an important technical feature/

An example of this slightly mystificatory approach can be found on the BFI DVD of A Cottage on Dartmoor (UK 1929).

“A Cottage on Dartmoor is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1 and at is historically accurate frame rate of 22 frames per second, using the restoration negative elements from the BFI National Archive. The film was transferred at 24 PsF (progressive scan} and restored using HD-DVNR and MTI digital restoration systems. This master was then slowed down to its correct frame rate of 2 fps. Because of the processing involved at this stage, some slight combing and image stutter may be detected when viewing.” The technical abbreviations apply to restoration and transfer technologies – described in detailed on the Web]. What is not stated in plain English is that for every 22 frames a further three would seem to have been added.

A particular example from the last year or so is Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (La Passion De Jeanne D’Arc, France 1928). The film was screened at the 2012 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. The film was screened in the local Cathedral with an orchestral accompaniment. This was presumably the reason why DigiBeta rather than 35mm was used. The Catalogue noted that this was ‘transferred at 20 fps’. However it appears prior to the screening the orchestra pointed out that they had prepared using the DVD. So the digital version was run through a computer to add extra frames and run at 25 fps. Fortunately I had decided to watch the alternative 35mm screening. It seems to me that Dreyer’s film is rigorously constructed both in terms of shots, shot length and shot alteration: just the sort of film where step-printing will have a negative impact.

In the UK Dreyer’s film suffered even more. There have been two screenings over the last year or two in this region where a screening with ‘live music’ has used the version of the film issued by Masters of Cinema on DVD and Blu-Ray. I checked with Masters of Cinema and they advised that they had added extra frames to this version to raise the frame rate from 20 per second to 24 or 25 per second.

And readers of Sight & Sound are likely to be misinformed or at least confused regarding this. In the December 2012 issue there was an article by Michael Brooke The Maid remade. The article discusses the film restoration and the Eureka Masters of Cinema version. Brooke does not actually give the frame rate directly but he includes an observation “they were [keen] to preserve Dreyer’s original intertitles and present the film at their preferred projection speed of 20 frames per second”. The article certainly implies that these video versions re-present the film at the original 20 fps. A similar comment was made on the BBC Film Programme when the DVD / Blu-Ray was reviewed there.

I wrote to the Letter Page of Sight & Sound as follows:

“Michael Brooke is quite right to praise Dreyer’s Jeanne d’Arc lidelse og dǿd (Joan of Arc’s Suffering and Death, 1928) however he is wrong to suggest that the DVD and Blu-Ray recreate the 20 fps running speed. DVD runs at 25 fps and Blu-Ray at 24 fps. What seems to be the actual case is that these disc version recreate the running time at that speed, presumably by adding an extra four frames for every 20 to the original. This is all right for domestic users if they choose this version. However, the Blu-Ray has also been used for theatrical presentations with live musical accompaniment. Michael Brooke notes that an earlier version ‘controversially replaced intertitles with subtitles (thus interfering with the editing rhythms)’. I would reckon that adding additional frames to a film that is so rigorously shot and edited would have a similar effect. I would suggest that as well as following Dreyer’s preference ‘that the film be shown in silence’ that theatrical presentations should use a 35mm print. These do exist. “

For the first time in my experience I received an emailed response from the Letter Page Editor at Sight & Sound:

“ Dear Keith, Thank you for your letter on Michael Brooke’s piece. However I’ve no doubt that Michael is well aware of the technicalities of presenting a 20 fps film within a 24 fps format – just that it seemed irrelevantly technical in the context of his Joan of Arc piece. You may want to read a piece he recently wrote for the BFI Website: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news/how-do-you-solve-problem-potemkin Best, James Bell.”

I checked out Michael Brooke’s Blog and, indeed, he does discuss the step printing in the film.

“Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-ray of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) does something similar [to the Battleship Potemkin video]. Respecting the Danish Film Institute’s estimate that the optimum projection speed is 20 fps, four additional frames were created every second using identical methods – this time, five individual frames are followed by a duplicate. Again, the result is perfectly smooth, although in this case they’ve also included the more familiar 24 fps version.”

The result may be smooth, but whether it is accurate is a mater of debate. Brooke’s makes great play in his article regarding the 20 fps rate and also comments how the substitution of sub-titles for intertitles ‘interferes with the editing rhythms’ – touché extra frames! I did reply to James Bell suggesting that whilst Michael Brooke’s might know about this but not all the readers might, and requesting that the letter appear. It did not.

In the March 2013 issue of Sight & Sound there was a letter from Caroline Yeager at the George Eastman House film archive. She chided the organisers of an UK tour who used a DVD version of Beggars of Life (USA) despite also having live musical accompaniment. So I took the opportunity to raise the issue again on the S & S Letter Page, but with no greater success.

Despite claims by some exhibitors and critics about the quality of DVD and Blu-Ray video versions, neither is a theatrical format. Apart from the inferior quality of the screenings presented to audiences this practice is likely to militate against a quick conversion of digital projectors to accommodate the FIAF specifications. And even when this happens the rather inaccurate use of language means that audiences will never be sure whether .. fps means the original frame rate, or the step-printed frame rate. This offers serious irony. When sound arrived a large part of the silent heritage was junked and commonly the films were projected at the wrong speed: a practice that lasted into the 1970s. Archivists and historians like Kevin Brownlow were pioneers for a sea-change leading to ‘‘presenting the films as they were originally screened’’ Now an equivalent change to that of the arrival of sound is taking place in the industry. It is likely that digital copies will have a much shorter archive live than celluloid, we may actually lose painfully restored masterworks in their original form. It is certainly more difficult to see them in their original form than a few years ago. Thus history repeats itself as tragedy; perhaps the blurb on many digital copies is the element of farce!