This Soviet classic has been re-released by the BFI on a DCP: sadly there is not a 35mm print available. However, it is a good transfer and the source is high quality: also as the recommended frame rate is 24 fps there is not a problem with step-printing or running too fast. The actual print used is from the Nederlands Filmmuseum. This was screened at Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 2004. It is the most complete print known of the film. The original release was 1839 metres, this version is 1785 metres. It includes the chapter divisions which the author Dziga Vertov and his colleagues used in the film. The digital version now on release is a restoration by the Eye Institute and Lobster Films. Both are in the forefront of archival work on early cinema. Moreover the restoration has taken the opportunity to re-instate at least some of the missing footage. Included is the following:

“the one that shows, point blank, the moment a baby is being delivered , the most direct manifestation of Vertov’s direct cinema, which may be the reason that it has been censored from the Dutch print.” (Yuri Tsivian in the 2004 Giornate Catalogue).

Tsivian also explain the ‘provenance’ of the print. An opening title provides this information on the DCP. Dziga Vertov visited Western Europe early in the 1930s. He bought with him a print of the film from the Soviet Union and this was the print retained in the Nederlands. Apart from the importance of providing an almost complete version of the film this also provides a parallel with another important Soviet filmmaker. The most complete surviving print of Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potemkin, 1925) is the version that Sergei Eisenstein and his colleagues bought with them to London and which was screened at the London Film Society with Edmund Meisel leading the musical accompaniment composed for the release in Germany.

Vertov and Eisenstein had rather different approaches to film and both were inclined to express their approaches with decided emphasis. In fact there were frequent and sometimes volatile disputes among the Soviet artists in this period: not surprisingly as they grappled with the form and style appropriate to the new society and new culture. Yuri Tsivian discusses the feud in the seminal study, Lines of Resistance Dziga Vertov and the Twenties (2004, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto). He suggests that there may have been a personal dimension to the arguments. That may be, but it would seem that in fact these two leading filmmakers had as much in common as they did in difference. I was struck revisiting Man with a Movie Camera by shots, especially in industrial settings, that reminded me of the films of Eisenstein, especially Strike (Stachka, 1924). Moreover, their use of montage has more in common than, say, that of Eisenstein and Pudovkin. Both Vertov and Eisenstein were concerned to record reality, but also to address the social relations involved in that reality. Their major difference was that Eisenstein tended towards dramatisation: Vertov emphasised that of the record. Eisenstein’s reflexive techniques aimed to position the audience in relation to the film: Vertov’s use of reflexivity aimed to draw the audience into the tapestry of the film itself. It struck me that just as among cinematic pioneers the Lumières are seen as proponent of actuality and Méliès of fiction, so in political cinema these two great artists can be seen as parallel proponents of two approaches, to a degree complementary.

A main title credits Dziga Vertov as “Author and Supervisor”, not as frequently printed in reviews and commentaries, ‘director’. He was the lead comrade in a movement of ‘kinocs’:

” We call ourselves kinoks as opposed to “cinematographers,” a herd of junkmen doing rather well pedalling their rags.” [Annette Michelson adds a footnote}, (“Cinema-eye men”). A neologism coined by Vertov, involving a play on the words kino (“cinema” or “film”) and oko, the latter an obsolescent and poetic word meaning “eye”.” (Kino-Eye, 1984)

A trio of kinocs were key to the filmography attributed to Vertov in the 1920s, though other comrades also contributed: the collective were also known by the title Factory of Facts. Aside from Vertov there was the cameraman Mikhail Kaufman and the editor Elizaveta Svilova: both of the latter are key to the final film. We not only see Kaufman repeatedly within the frame, but his positioning and framing with the camera contribute greatly to the visual impact. And Svilova, also seen several times in the film, produced [under Vertov’s supervision] the dazzling sequences of shots that compose the film.

Man with a Movie Camera is composed of seven reels and the Nederlands print retains the numbered divisions between parts. There is the Introduction and then the following six sections. The film opens with the Credits, importantly this stresses that this is a film

‘WITHOUT THE HELP OF INTERTITLES’

and a film

‘WITHOUT THE HELP OF A SCRIPT’.

The collective’s earlier films had made extensive use of title cards. One of the radical aspects in Kino Pravda was the use of title cards, often carefully designed by fellow constructivists. In fact, as one critic, Khrisanf Khersonsky, pointed out:

“A film without intertitles, says Vertov. But this is not true [either]. There are various kinds of intertitles, and what, if not intertitles, are the shots of, for example,: a sign on a church saying ‘Workers’ Club’, an urn with the words ‘Citizen, keep things Tidy’, edited into a sequence of a girl washing, shop[ signs and so on.” [The majority of these are translated in the DCP by English subtitles]. (Lines of Resistance).

But the status in the film of a title card and of words within a frame is different. This distinction re-enforces the emphasis on the recording of reality, and avoiding the didactic commentative card. Something similar applies to the claim regarding the absence of a script. Vertov and his colleagues were criticised for not producing scripts before a production. The State financing body Goskino [which fired these filmmakers] relied on this to allocate resources. In fact, Vertov did produce ‘analyses’ beforehand: though much less detailed than a printed script. Indeed it is apparent that there is an overall structure to the film and that the relationship of parts to other parts and to the whole is very carefully worked out and calculated.

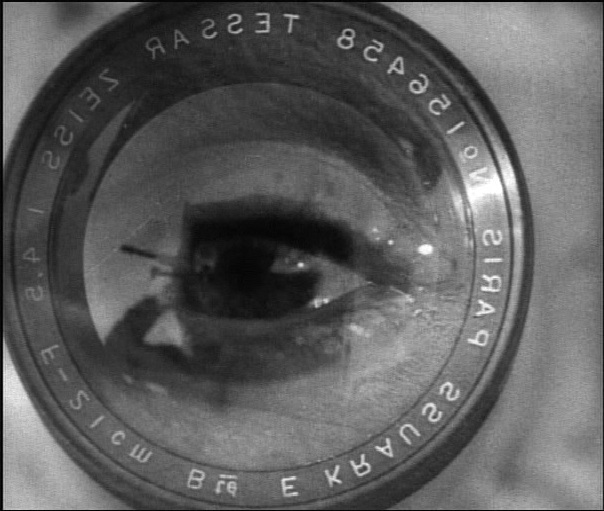

The film introduces itself in an extremely reflexive manner. We enter a film theatre, the projectionist prepares the print, the audience enters and the musicians appear. Now the film ‘proper’ begins, on the screen within a screen. This is kino-eye:

“When The Man with a Movie Camera was made, we looked upon the project in this way: … we raise different kinds of fruit, different kinds of film; why don’t we make a film on film-language, the first film without words, which does not require translation into another language …” (Kino-Eye, 1984).

We now enter the world of the cameraman, Mikhail Kaufman, but it is both the world of the cinematic collective and the larger world, the Soviet Union and its attempts to build a new society. In fact, there would have been several cameramen involved in the filming, since we frequently see the cinematographer himself in the frame. It is also a camera of record, sometimes apparent to the subjects, sometimes apparently not.

“To be able not to act [the requirement for documentary] – one will have to wait a long time until the subject is educated in such a way that he won’t pay any attention to the fact that he is being filmed. …

Following that line of thought I constructed a sort of tent, something like a telephone booth, for Man with a Movie Camera. There has to be an observation point somewhere. So I made myself up as a telephone repairman. There weren’t any special lenses, so I went out and bought a regular camera and removed the deep-focus lens. Standing of to the aside I could still get things very close up …” (Interview in Imaginary Reality, 1984).

At other times the cinematographer is emphatically in the frame. Lying by rail tracks to film an oncoming train: climbing up a tall tower to film from its top: standing in tram tracks in order to catch the approaching or retreating vehicles.

The first of six sections introduces us to the city and its people. This is the start of the day, we see silent buildings and empty streets. Gradually people rise and commence the day.

The second section shows us the city in full swing. People are active, machines move: the trams, a frequent sight, move round the city. And the urban crowds commence their activities.

The third section shows us Svilova at work, editing the film. Then we see various cultural actions: weddings, divorces, birth, death and funeral’s We also see the treatment of the victim of an accident and a fire brigade racing through the streets.

The fourth section shows labour processes in full swing. There is a contrast between cosmetic activity for women and women involved in manual labour. We see both business activity, such as a telephone switchboard, and the heavy manual labour underground in a mine.

With the fifth section formal productive labour comes to a halt. The section’s focus is on cultural and leisure activities. These include entertainments, sport and beach activities.

The final sixth section brings an overt political focus to the film. There are shots of both Lenin and Marx: and shots of the Soviet Workers’ Clubs: we see a woman shooting. Another image references the rise of the fascist threat. The key image is a collapsing Bolshoi Theatre, using superimpositions. Tsivian comments on this:

“Along with some other innocuous objects and artefacts from the Imperial era, soon after 1917 the Bolshoi was caught in a process which I venture to call “revolutionary symbolization”. In some cases – like ours – this symbolization could take the form of symbolic destruction …” (Lines of Resistance).

This final section also included references to radio, another technological and cultural form that was extremely important in the Socialist State. For the Kinocs radio was an important component for their new language: the next film produced by Vertov was Enthusiasm (Symphony of the Don Basin / Entuziazm, 1931), which used sound alongside the visual components in an extremely adventurous manner. Vertov, in an article on the film, commented,

“[My article] … speaks of Radio-eye as the destruction of the distance between people, as the capacity of workers of the entire world not only to see but simultaneously to hear one another.” [in Lines of Resistance].

But the most important component in this final section is the return to the audience we encountered in the Introduction. An increasing tempo alternates shots of the cameraman, shots by the cameraman and shots of the audience watching in the theatre. So that the film resolves itself finally with a reflexive manner which aims to involve audiences in the tapestry of the film.

The music track on the DCP is provided by The Alloy Orchestra. They provided the accompaniment at Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, though on this occasion the print screened was from the George Eastman House. The Alloy Orchestra went back to the musical notations that Dziga Vertov provided for the original screenings. These were translated for the occasion by Yuri Tsivian:

“Vertov’s handwritten notes outlining a “music scenario for The Man With a Movie Camera – five pages of guidelines mapping out what kind of music Vertov wanted to go with what sequence. These written notes were intended to help three composers employed by the Music Council of Sovkino for the cue sheets they were supposed to write for an orchestra assigned to play for the film during the opening night on April 9, 1929;

[there is Verov’s] permanent tendency to start a sequence with conventional music steadily growing into the pandemonium of noises, his desire to “freeze” music, reverse it or make it sound “slow-motion” in the same manner as films shot do …” (Griffithiana 54 , October 1995).

This is the performance that The Alloy recreate for the DCP. However, whilst I remember the use of noises, both productive and human, in the 1995 performance I think they have taken advantage of digital technology to add to these.

One of the strongest impressions from the film is the almost frenetic pace of the editing. Shot constantly follows shot. Some of these offer some sense of continuity, many suggest counterpoint and discontinuity. The influence of Kuleshov’s ideas on montage appear: as the film constructs a series of images that are actually separated by time and space: the weddings utilise film shot both in Odessa and Moscow.

The framing of Kaufman’s camera work is impressive. The film uses a range of camera shots and of editing techniques as varied as any in this period of cinema. Annette Michelson describes the film thus:

“This film, made in the transitional period immediately preceding the introduction of sound and excluding titles, joins the human life cycle with the cycles of work and leisure of a city from dawn to dusk within the spectrum of industrial production. That production includes filmmaking (itself presented as a range of productive labour processes), mining, steel production, communications, postal service, construction, hydro-electric power installation and the textile industry in a seamless organic continuum, whose integrity is continually asserted by the strategies of visual analogy and rhyme, rhythmic patterning, parallel editing, superimposition, accelerated and decelerated motion, camera movement – in short, the use of every optical device and filming strategy then available to film technology. …. ‘the activities of labour, of coming and going, of eating, drinking and clothing oneself,’ of play, are seen as depending upon the material production of ‘life itself’. (Introduction in Kino-Eye).

Whilst the film’s editing is distinctive even in Soviet cinema, there are parallels to other film works. I have mentioned the parallels with the editing of Lev Kuleshov and in industrial shots with Eisenstein’s films. In part four we see shots of a spinning machine which parallels Eisenstein’s shots of a cream separator in The General Line / Old and New (Generalnaya Linya / Staroye i Novoye, 1929). The frequent tram shots at one point reminded me of Boris Barnet’s fine The House on Trubnaya Square (Dom na Trubnoi, 1928).

The film, as was often the case with the films from the collective, provoked furious discussion. Vertov records screenings followed by discussions in the Ukraine. Tsivian in his volume provides the record of such a discussion as well as the varied responses to the film in print.

“[The Society of friends of Soviet Cinema] The discussion became extraordinarily sharp only around the middle of the evening. It was the film’s ideological aim that suffered the greatest bombardment.

“The authentic life of the country is not shown in the film,” said the Editor of the magazine Ekran. “This comes about because the predominant role in the film is played exclusively by the form, good stunts, excellent montage, and … nothing else.”

Comrade Berezovsky’s words were disputed by Comrade Gan, The film poses problems of the way of thinking man in society far more seriously than it is posed in all our feature films, with their deliberately emphatic interpretation of the world.” (Lines of Resistance).

Vertov’s films, like some of the other avant-garde art of the period, was found really challenging: now, when so many filmmakers, have followed his example, the work can be more accessible. However, the debate also reflected the contradictions of opposing political lines in Soviet art, a debate that reflected the more fundamental struggle between political lines in the party and leadership. Sadly, the radical elements lost out and were increasingly suppressed in the following decade. So that Vertov, though he made at least two more fine films, was not able to produce anything equally radical in the following years. It is worth noting that this was the final collaboration between Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman: the latter was less impressed with the overall structure and complexity of the final film,. He went on to direct documentary films himself.

If the form and style of the film is more appreciated in the contemporary world of cinema there is frequently a less intelligible response to the political and ideological line of the film. In 2013, under the title Ukraine: The Great Experiment, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto offered a programme of other radical films produced in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in the late 1920s. The Catalogue entry by Ivan Kzolenko made a reference to the work of the Kinocs in the Ukraine, commenting

“But not by chance was the totally apolitical Man with a Movie Camera different from Vertov’s other agit-films.”

I find this comment difficult to equate with the film that I have seen a number of times. As Tsivian argues in Lines of Resistance the film is the accumulation of a decade of experimentation by the Kinocs group. And it is an intensely political work, the treatment of the Bolshoi Theatre above is a single example. Tsivian also provides a longer discussion of how the film exemplifies the analysis of Karl Marx. One example is a series of shots of coal mines and aerial conductors:

“Vertov tried to connect inside the viewers’ mind, the production of coal – the economic cause – with the economic effect: the production of electricity”.

Tsivian also offers parallel examples from earlier films. He continues,

“What all three exemplify is that, early one, the ambition of Vertov’s cinema becomes not to show, but to think – that is, to disclose invisible connections between things.” (Both in Lines of Resistance).

So Man with a Movie Camera is not merely [as Comrade Berezovsky comments] an exhilarating bag of tricks and technical devices. As Comrade Gan argued it offers an ‘interpretation’ of the world. And the world in question is the world of Socialist Construction, still a relevant concept in 1929. The structure of the film offers the processes of labour and of the labourers. Included in this is the labour process of film itself. Annette Michelson points out how,

“Vertov seems to take or reinvent The German Ideology [which he would not have read] as his text, for he situated the production of film in direct and telling juxtaposition to that other particular sector, the textile industry, which has for Marx and Engels a status that is paradigmatic within the history of material production” (Introduction in Kino-Eye).

Man with a Movie Camera is a film about social relations, and that includes the underlying social relations that are not apparent to the superficial surface viewpoint [i.e. ideological]. Hence the film continuously cuts between the variety of social relations, productive, cultural and personal, in modern society. And in the final section the audience, that is the ‘workers and peasants’ of the Soviet Union, are integrated into that tapestry of relations. So the film is propaganda in the socialist sense, advanced ideas for advanced workers.

In pointing to this it must be noted that there is an unexplored space in the film: agriculture and the peasantry. This part of the socialist state had been explored in some of the earlier films of the Kinocs. But the focus in this film is entirely urban. Given that the 1929 is a key year in the introduction of collectivisation: Eisenstein’s compelling The General Line / Old and New treats the issue: this is an analysis that needed treatment, either in the film or separately.

The film does fall into the category of City Symphonies: and one comparison frequently drawn is with Ruttman’n’s Berlin: Symphony of a City(Berlin: Die Sinfonie einer Gross-stadt, 1927). However, these two films offer vastly different treatments and approaches, partly explained by Berlin being a centre of Capitalist relations whilst the Soviet cities were parts of an ongoing Socialist project. One key difference is the treatment of people. My memories of Berlin are of a series of abstract buildings and spaces: last time I viewed it I was surprised to see that there are quite a number of urban citizens in the film. Man with a Movie Camera is centrally about the people who inhabit these cities and their relations to each other and to the buildings and machinery that surround them.

The 2013 Giornate Catalogue makes one valid point:

“The fact that the film was made in Odessa and partly in Kyiv and Kharkiv is often mistakenly disregarded by researchers.”

In fact some publicity for the re-release [not the BFI’s] mistakenly referred to ‘filmed in Moscow’. Vertov and his fellow Kinocs had already filmed The Eleventh Year (Udynadsiatyi, 1928) for the All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Directorate. The films funded by Goskino in Moscow had increasingly been subjected to criticism, both for the working practices and the films’ treatments. As the 2013 programme demonstrated there was a radical space for film in the Ukraine at the end of the 1920s. So much of Kaufman’s work was filmed in the Ukrainian cities. However, following the continuing practice of using ‘found footage’ there is also Moscow footage, presumably from earlier films or film out-takes.

These circumstances remind us that the film was one of the great expressions of Socialist art in the 1920s: but a Socialist Art that was under attack from what is best described as reformist cultural values. Vertov was well aware that his film did not exactly fit the developing cinematic values in the Soviet Union.

“The film Man with a Movie Camera is an experimental film, and as such may not immediately be understood and may be destroyed in the days immediately following the completion of the auhtorial montage.” (Lines of Resistance).

As an experimental film it has exerted an immense influence, including on filmmakers who did not necessarily share the Kinocs’ socialist values. But those values are equally central to the quality of the film. Vertov writes, detailing material from the film, of this ‘visual symphony’,

All this … – all are victories, great and small, in the struggle of the new with the old, the struggle of revolution with counterrevolution, the struggle of the cooperative against the private entrepreneur, of the club against the beer hall, of the athletes against debauchery, dispensary against decease. All this is a position won in the struggle for the Land of the Soviets, the struggle against a lack of faith in socialist construction.

The camera is present at the great battle between two worlds:… (Kino-Eye).

Imagining Reality The Faber Book of Documentary, Edited by Kevin MacDonald and Mark Cousins, Faber and Faber, 1984

Kino-Eye The Writings of Dziga Vertov, Edited by Annette Michelson and Translated by Kevin O’Brien, Pluto Press 1984.

Lines of Resistance Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, Edited by Yuri Tsivian, Le Giornate Dell Cinema Muto, 2004.

Griffithiana was a Journal published jointly by a Cineteca del Friuli and Le Giornate del Cinema Muto.

Stills courtesy of Il Giornate del Cinema Muto 2004.