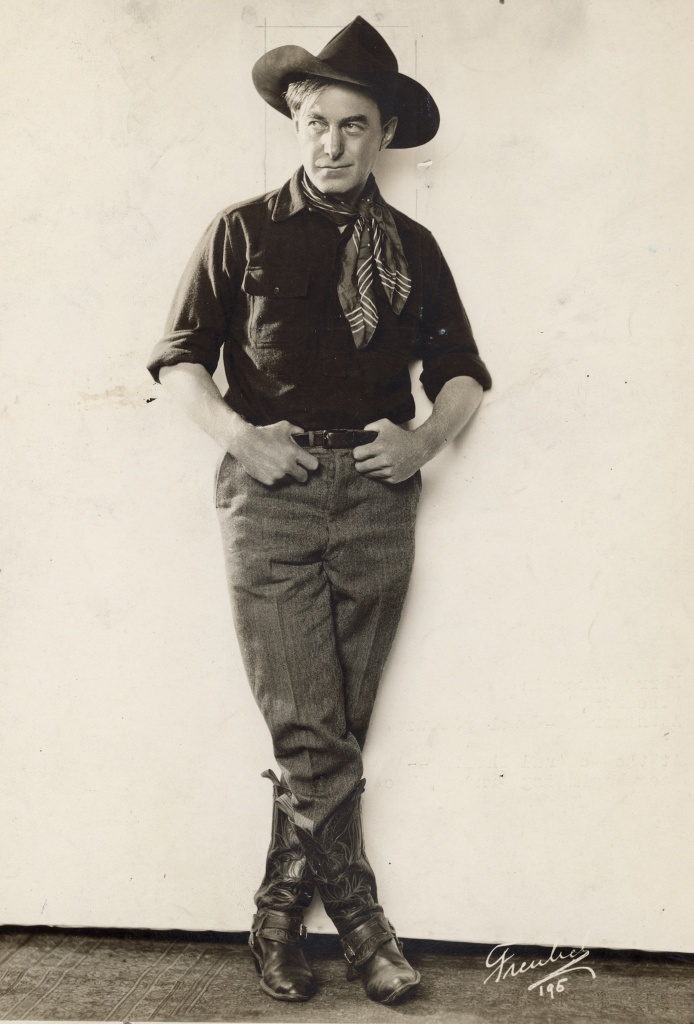

A typical Suzanne Grandais pose in ‘LES DEMOISELLES DES P.T.T.’

Suzanne Grandais, with Léonce Perret, featured in the ‘French Stars’ programmes at the 38th Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. I will discuss the other, Mistinguett, later.

Suzanne Grandais was born in Paris in 1893. She entered the theatre at the age of five and worked as both an actress and a dancer. She then had some small roles in short films and in 1910 signed with Gaumont, then one of the most important film studios not only in France but across the international film arena. In 1913 she moved to a German studio producing in France for a series, ‘Série artistique Suzanne Grandais’. She was an extremely popular film actress both in France and wider. She died young in a car accident in 1920. An obituary at the time described her as an

“exceptionally gifted and really beautiful young actress.” [Jay Weissberg in the Festival Catalogue].

As recently as 2009 a French novel still mourned her passing.

Léonce Perret was her frequent co-star at Gaumont and also the director of many of her films. On screen he often played a rather jovial character with a strong sense of mischief. As a director he worked on both comedies and melodramas. He was skilled with actors and was frequently innovative in his direction of cinematography and lighting.

The four films in the programme were a drama and three one reel comedies, a genre at which both Grandais and Perret were adept. They almost always played a couple, sometimes married sometimes prospective lovers. This was the time when European actors were starting to receive identified credits, leading to a star system that was also developing in the USA. Gaumont, with Grandais and Perret, was in the forefront of this development.

Le Chrysanthème rouge, 1912 with a English language title of Love’s Floral Tribute.

Suzanne plays a young woman of the same name, [common across these titles]. She has two suitors, one of whom is Léonce. To test them she gives them the task of bringing a bouquet of her favourite flowers; carefully not identifying the blossom. We see both suitors buying multiple bouquets at florist stalls; I think these were on the banks of the Seine. On their return Suzanne tells them,

“I only like Chrysanthemums.”

The two suitors rush off; return to be told,

“only red ones.”

Léonce now rushes off but this rival stays and whilst Suzanne is absent cuts his hand and stains the flower red. A shot dramatically rendered with stencil colouring. On his return Léonce find his rival with Suzanne bandaging his hand and smilingly shaking her head. The gentleman, Léonce shakes the hand of his rival and kisses the hand of Suzanne, then leaves.

The drama is shot with real economy and some interesting locations. Suzanne’s characterisation of the young woman is excellent and sympathetic. Jay Weissberg in the catalogue described her as

“simply a self-assured woman re-writing social norms on her own terms.”

The surviving 35mm print had been copied onto a DCP and including the coloured flower; it ran 13 minutes.

Le Homard / A Lucky Lobster, 1913

This title was

“the first in Beaumont new series “Léonce”, based on the director-actor’s cinema persona…” (Festival Catalogue).

The opening was a slit screen of two full-length shots of Léonce in oval frames. We then move to a seaside resort where Léonce and his wife, Suzanne, are on holiday. They visit the local quay where Suzanne sees fishermen selling lobsters. The price is eight francs which Léonce decides is too much. Suzanne is angry at this and complains bitterly when they return to their lodgings. To placate her Léonce offers to himself catch a lobster. In fact, whilst hiring the fishing utensils and waterproof clothing Léonce bribes a fisherman to let him have a lobster. In a wild night with winds and high seas Suzanne worries over her husband. He is actually at the local cinema watching a comedy.

“the latter action sees a clever triple-screen in which Suzanne, fearful for her husband’s safety, prays on the left-hand side while waves crash against rocks in the center and Léonce roars with laughter in the theatre on the right …” (Festival Catalogue).

At first Suzanne cares lovingly for her husband when he returns with the lobster. But the fishermen’s call for the gear reveals Léonce’s ruse. Interrupting Léonce as he shaves Suzanne daubs him with the shaving cream.

A triple-screen with Suzanne on the left and Léonce centre-frame on the right

The row revolves later on the beach. Suzanne is paddling and Léonce watches her through his binoculars as she evinces distress. In a clever sequence of iris shots Léonce sees her distress, runs to assist and we see that the cause is a Lobster clinging to her backside.

Re-united, the couple enjoy the lobster in a meal at the lodgings,

“in the American way.”

This title shows off the talents of both Léonce and Suzanne. Her character

“embodying a loving but strong minded woman who won’t be made anyone’s fool, though in the end she is game for a joke even when it’s on her.” (Festival Catalogue).

On screen Léonce is typically playful and mischievous. Off-screen the story and characters are clearly presented and he uses innovatory techniques, such as the triple-screen with Suzanne, sea and rocks and Léonce and later the editing of the iris shots in the beach sequence.

We watched the longest surviving version on DCP, fourteen minutes. But then we also saw a three minutes extract on 35mm with the original stencil-colour of the beach sequence. A charming and impressive one-reel production.

Les Épingles / For Two Pins, France 1913.

This is a typical marital comedy with Perret and Grandais. Léonce has bought Suzanne a present, a shield for the hat pin she wears. However Suzanne is adamant that she will not us use it. As Suzanne prepares to go out Léonce points out to her the newspaper report of a new local ordinance requiring women to wear a shield over their hat pins. Suzanne firmly refuses, so as they bid goodbye with an embrace, Léonce pretends that the hat pin has pricked him in the eye. The servant is sent for the doctor. As he treats Léonce the latter lets him in on the trick. But Suzanne is listening at the door. So she now pretends to have fallen over and injured her ankle. The doctor, aware of both fake injuries, prescribes ‘joke’ remedies. As the injured parties lay on the bed Léonce strokes Suzanne ankle and she kisses his eye:

‘laughter,’ “The best remedy.”

The couple are reconciled as the servant returns with the bizarre remedies; her face when she sees them is a picture.. And Léonce shields the couple’s kiss from the camera: a typical trope. Screened on 35mm.

Les Nuage Passe / A Passing Cloud, France 1913.

Another marital tiff; this one over who can smoke at the breakfast table. Léonce does so but objects when Suzanne follows suit. They retire to their separate rooms. Suzanne attempts a reconciliation but the connecting room is locked; Léonce lies smoking on his bed. Then two mice invade Suzanne’s bedroom.;

“Léonce, Léonce. Help! Help!”

So the husband comes to the rescue and the couple once again lie together on the bed. In a n nice closing touch a statue of Cupid becomes animated and fires an arrow at the couple.

This used a 35mm print with tinting; and when Suzanne is threatened by the mice the tinting is green, changing to amber when we see Léonce respond. .

La demoiselle des P.T.T. / Shooing the Wooer, France 1913.

The English title refers to the plot; the original title refers to the offices of ‘Post, Telegraph and Telephones’ Here Suzanne appears without Léonce on screen , though he may have been behind the camera. Suzanne sets out to work at the P.T.T., using the tram, where an ‘old bourgeois gentleman’ is so smitten that he follows her to the office. Here he attempts to ‘woo’ Suzanne who smartly rebuffs his advances by bringing her window down on this hand. But unrepentant he then tries to chat to her by telephoning her office. Here the film uses a three-way split screen, with the gentleman, Oscar, on the left: the telegraph wires in the middle: and Suzanne on the right. His last resort is to send a letter, delivered to the office by his manservant. Suzanne sends him a tart reply.

“Although the film is missing a letter insert, ‘De Bioscop-Courant’ describes the letter as contain the following lines from La Fontaine’s tale. “The Ass and the Lapdog!”: “We should never force the talent we receiv’d from nature, for then everything we do will be ungraceful. A lumpish creature, tho’ he take the utmost pains, will never catch a graceful air”.” (Annie Fee in the Festival Catalogue).

When Oscar calls with flowers he reads the letter, much to the amusement of Suzanne and her fellow workers.

Annie Fee points up an important contextual aspect to the film’s release in March 1913.

“Four years earlier, female telegraph and postal workers had gained the sympathy of the French public when the politician Julien Simyan called them saloperies and sales poupées (whores and filthy dolls), His sexist insults triggered the first general strike of postal and telegraph workers, ….” (Festival Catalogue).

The film was part of the “Oscar ” series which starred Leon Lorin. The director is unknown but could possibly have been Perret; the split-screen is similar to that in Le Homard. However, the film has a notable caustic toner and whilst Suzanne is, once more, a self-sufficiency young woman, here she is young working woman with a faintly anarchic touch. We also enjoyed a 35mm print for this film

This programme of five titles opened the 38th Giornate. It was a real pleasure to watch and set a delightful tone for the coming week. This was enhanced by the musical accompaniment by Gabriel Thibaudeau at the piano. This was at times chirpy, at times dramatic and at times lyrical.