Alice Guy Blaché at the Kennington Bioscope

Posted by keith1942 on June 20, 2021

Solax – The House Built by Alice Guy Blaché.

June 2nd at 7.30 p.m. and available until June 30th on Kennington Bioscope You Tube Channel.

‘Women and the Silent Screen’ is a conference held bi-annually in New York City. Number 11 this year was on line between June 4th and June 6th. A series of programmes had papers and discussion on the work and art of women film-makers in early cinema; the central theme this year was ‘Women, Cinema and World Migration’.

Before the Conference there was tribute screening to the important pioneer of early cinema, Alice Guy Blaché and this was made available on the Kennington Bioscope. Alice worked as a secretary at the firm of Gaumont, soon to be come the first major production company in the new cinema industry. She was a pioneer in making short narrative films as the Head of Production at Gaumont between 1896 and 1906.

In 1907 she married Herbert Blaché and the pair moved to the USA to work for Gaumont in that territory. In 1910 she, with partners, formed the Solax Film Company, a production company based first in an ex-Gaumont Studio in New York and then in a new production facility in the film town Fort Lee, near New York. She continued directing and producing films up until 1920.

The programme streaming on the Bioscope offers nine titles from her period at Solax. The titles included present Alice Guy as producer, writer and director. A number of archives have contributed including producing newly digitised versions. As can been seen the surviving information available varies. The Bioscope also offers musical accompaniments streamed alongside the titles. The programme is in two parts and runs for nearly three hours. Programme notes are provided on the Conference web pages. The streaming includes introduction by the Conference organisers and the Bioscope.

Frozen on Love’s Trail. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1912). running time: 13:30 minutes. Source Archive: Eye Filmmuseum. Music: Costas Fotopolous.

An early western. The print transfer has Dutch title cards with English sub-titles provided. The alternative Dutch title was

‘Self-sacrifice of a redskin’.

Mary is the daughter of the commander of a military fort. Set in winter, one day she is given a lift into the fort by an Indian courier delivering mail with a four dog team. Clearly smitten the Indian offers Mary a necklace but when an officer, Captain Black, intervenes she is shamed into throwing the necklace away. Later the Indian is sent with important mail over a difficult mountain route. Out riding, Mary has fallen from her horse and is found unconscious by the Indian. He wraps Mary in his great winter coat, straps her to the sledge and staggers in the cold back towards the fort. Overcome, he sends the dogs on with the sledge and Mary to the fort. A search party discovers her and the dogs; and later, the body of the dead Indian. Remorsefully Mary searches and finds the necklace she threw away; the final shot.

This film was shot during a snow storm in the environs of Fort Lee. The use of the exteriors is impressive; especially in a sequence as the Indian staggers across a bleak and snow covered landscape. The cinematography is predominately in mid-height long shot. There are a couple of camera movements during the rescue but these are like adjustments rather than proper pans. The print does have some flaws due to deterioration over the years. Whilst the European migrant characters have names, the Native-American is only ‘Indian’ [or ‘redskin’]. However, as is common in early western produced in eastern studios the representation of the Native-American is far more sympathetic than in the later Hollywood examples of the genre. However, it is nearly always the case that a Native American sacrifices for a European and does not really posses proper autonomy as a character. The character was apparently played by a European actor, Bud Buster, with added make-up. One review describes the character as a ‘half-breed’, which fits the look on screen.

The Native American does come off better than the dogs. Their intelligent completion of the rescue does not seem to have been lauded by characters in the film; nor by reviewers later.

Two Little Rangers. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1912). running time: 14 minutes: one reel, 300 metres. Source Archive: Eye Filmmuseum. Music: Andrew E. Simpson. The transfer had Dutch title cards with English sub-titles provided.

This is an action packed western with a fairly complicated plot. The film opens in the postmaster’s store where ‘Wild Bill’ Grey overhears information about a gold shipment. The postmaster’s two daughters note Bill’s interest with suspicion. Back at his cabin Bill is revealed as a wife beater, interrupted in his violence by ‘kindly Jim’. This motivates Bill to seek revenge.

When the postmaster sets out with the gold for the station he is accompanied by Jim and followed by Bill. The actions of the last are closely watched by the youngest daughter. Bill finds the postmaster alone and after a struggle pushes him over a steep cliff. Bill plants Jim’s knife at the scene and the latter is arrested though innocent. However, the daughters suspicions lead to them following Bill and the older daughter finding and rescuing her injured father. Bill is pursued and wounded. Back at the store he confesses to the robbery and is forgiven by both the postmaster and Jim; he shakes hands with each in turn and then expires.

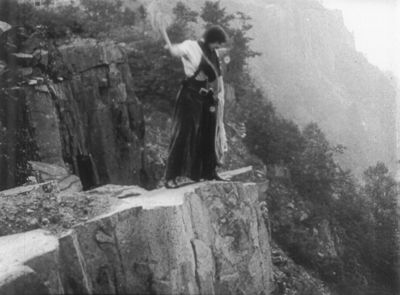

This is a really dramatic title and the the intensity is increased by the frequent use of close-ups, both revealing the emotions of the characters and showing important detail such as the knife or a clue of a piece of a torn shirt. The exteriors are impressive including the well-known Cliffhanger Point, a sheer cliff overlooking the Hudson River. The acting is at times over-emphatic with Bill and the younger daughter in particular using melodramatic stances. The older daughter is played by a regular leading player with Solax, Vinnie Burns. She was noted for her stunt work and the rescue of the postmaster, involving a lasso down Cliffhanger Point is impressive.

This is the earliest example that I have seen of domestic violence in a plot. Countering the victim-hood of the wife is the dynamic actions of the daughters. They are smarter than the male posse when Bill flees justice. In the chase and fight with Bill the girls let off volleys of shots from six-guns and then set fire to the cabin in which he hides.

The tinting in the film survives including that of red when the cabin takes fire.

The Strike. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1912). running time: 11:10 minutes. Source Archive: BFI. Music: Lillian Henley. Film Length 296.25 m (1 reel) (USA)

Set in a factory the lead character is Jack Smith, a union organiser. At the start of the film he is presented speaking powerfully to a meeting of the workers. He is supported by another character, not a factory worker, and labelled ‘Agitator. Jack visits the employer who dismisses the unspecified demands of the men. A meeting of workers outside is stirred up by the agitator and they stone the factory windows and then go on strike. A small committee of workers, at the instigation of the Agitator, plan to plant a bomb at the factory ‘at midnight’. Jack reluctantly draws the short straw.

Later we see him at home with his wife and daughter (Magda Foy). He conceals the bomb in a desk drawer and then leaves with the Agitator for a meeting. The Agitator carelessly flicks his cigarette end, missing the waste basket and a fire starts. At the meeting Jack addresses the workers. At home the wife puts the daughter to bed and then discovers they are both trapped in the bedroom by the fire. She is able to phone Jack with a telephone in the bedroom; a split screen shot. He leaves the meeting and races home. He is passed by his employer who drives him to his house and together they carry the wife and daughter to safety. The assumed explosion of the bomb is off-screen.

Next day, dressed in her Sunday best, the daughter brings a message to the employer from Jack.

“We’ve had enough of strike …… so let the whistle blow.’

The employer calls a clerk who is sent to sound the whistle. The employer leaves with the daughter, presumably to see Jack. The final shot is a close-up of the sounding whistle at the factory.

A ‘labour problem’ drama. Solax marketed it as “a big labor problem play, showing the human side of the employer,” Intriguingly there is an Australian film of the same title in the same year.

This is clearly a pro-capitalist and anti-worker property; likely reflecting that Solax itself was an example of commodity production and labour extraction. The pre-war years were a time of intense conflict between labour and capital. But the majority of violence was organised by the employer class, using vigilantes and the police in attempts to drive working class resistance away. Weighed in the Balance from the 1916 ‘Who’s Guilty?’ series has a rather different plotting of such violence.

In this version the workers, including Jack, are presented as suborned by an outside agitator; a trope that has had a long life in mainstream film and on television.

The film offers a series of short scenes, both interiors and exteriors. The camera is predominately in long shot and mid-shot. Jack in particular is given to melodramatic gestures.There is tinting but, for example, the red at the fire sequence seems very muted.

A Man’s a Man. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1912). running time: 9.5 minutes, 300 metres.. Source Archive: GEM. Music: Andrew E. Simpson. A drama of social justice.

There are two men in this melodrama; a Jewish pedlar and a rich gentile ‘Joy Rider’. The latter carelessly knocks over the pedlar’s tray of goods and then runs down the pedlar’s daughter who is playing with other children in the street. In what is an immigrant urban area a mob gathers and proposes to lynch the Joy Rider. He seeks refuge in the rooms of the pedlar, whilst the daughter lies dying in the next room. Showing great humanity, the pedlar hides the Joy Rider and deflects the mob when they appear. Now the daughter has died and the pedlar sends the Joy Rider away, refusing his offer of money. A year later the two meet at the grave of the daughter. The now penitent rich gentile carries a bouquet for the grave.

There are other film versions of the basic plot; but the ethnic dimension adds interest to the film. The characters are to a degree stereotypical in their representation. The conflict and the emotions are rendered in stark opposition. The tinting of the film survives. The final shot seems cut off and too short for full impact.

Starting Something. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1911). running time: 10:30 minutes, 300 metres. Source Archive: Library of Congress/Lobster Films Collection. Music: John Sweeney. A suffragette comedy.

This is a knockabout farce and the suffragette theme is more a plot device than a central focus. The opening scene is missing but explanatory titles inform us that Jones and his wife indulge in cross-dressing. The situation is exacerbated by Auntie; clearly the suffragette character dressed in masculine wear. She also suggests to the wife that Jones needs mental treatment with hypnotism. A suggestion of poison leads to chaos involving Jones, Auntie, a servant, a policeman and, finally, the wife.

Pathé Frères appear to have borrowed heavily from the plot in a film of the the same title in 1913. And the Solax production likely borrowed plot from an earlier Gaumont title directed by Guy in France; The Consequences of Feminism / Les résultats du féminisme (1906) and running only seven minutes. It seems that both films feature the same male lead, unidentified. This probably also explains the knockabout quality; the film feels like an earlier slapstick comedy. The production was shot at the Gaumont Flushing studio in Queen’s Borough; before the move to Fort Lee.

Part 2.

The latter title and the final four titles were all provided by the Library of Congress. And at the start of the second part there is a short video presentation by staff there. This includes the archive at Culpeper in the Blue Ridge Mountain foothills. The staff talked about preserving and restoring Alice Guy titles. And there is footage of the digital equipment and processes involved in transferring titles for on line use.

The Sewer. Directed by Edward Warren (Solax, USA, 1912). Produced with scenario by Alice Guy Blaché. Set design by Henri Ménessier. Running time: 18:40 minutes. Source Archive: Library of Congress. Music: John Sweeney. A crime drama.

Edward Warren was a US actor and director who started out with Solax and made films between 1912 and 1920. Henri Ménessier worked for Gaumont in France and then was sent to the US studio. He later worked with French film-makers in the USA, Albert Capellani and Léonce Perret. The notes on this title refer to its high production standards, quoting a US review:

“Every foot of the film brings a new thrill. In the long weeks of preparation, real sewers, manholes, rats, traps, switches, pulleys, divers and dens, mannikins and other contraptions used in the underworld, were gotten together with utmost care and attention to detail.”

Unfortunately the surviving print has suffered some serious deterioration and there are missing sequences described in this restoration by titles.

The film opens with wealthy philanthropists Mr and Mrs Stanhope distributing largesse to the needy at their home. They are visited by Herbert Moore who pretends to be a charity official but who is really a member of a criminal gang. We next see the gang at their hideout. They are teaching to young boys to pick pockets. This scene and a subsequent burglary are clearly modelled on Charles Dickens’ novel ‘Oliver Twist’; and the key young boy is called Oliver [Magda Foy playing a male part].

When the gang attempt to burgle the Stanhope’s Oliver is caught by the husband. However, moved by pity at this state he lets Oliver go. Back at the hideout the gang develop another plan which is overheard by Oliver.

When Mr Stanhope calls he is quickly seized and tied up. Then he is forced to sign a cheque for the gang and dropped by a trapdoor into a basement cell. But Oliver has secreted a note in his pocket with a key to a hidden door. He has also included a coin, made up as a mini-saw which Stanhope found on him in the earlier burglary.

Stanhope now has to escape via ‘the sewer’ of the title. This is an impressive sequence and, fortunately, there is no deterioration in the image. Menessier’s design captures the dank gloom and almost noir quality as Stanhope struggles through the underground passages. The gang are seized and the Stanhopes adopt the two boys.

Cousins of Sherlocko. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1913). running time: 12 minutes. Source Archive: Library Of Congress. Music: Colin Sell.

Mistaken identity leads to a criminal investigation.

This comedy involves cross-dressing; an action that was extremely popular in earlier comedies. A newspaper headlines informs the viewers that

‘Jim Spike is on the job again’.

When Fraunie sees the accompanying photograph he realises that he and Spike look similar. Shrugging of the issue he visits his girlfriend Sallie. But her father, having seen the article, throws Fraunie/Spike out of the house. The story now runs in parallel. In one Fraunie is seen and pursued by detective Sherlocko and his partner who mistake him for Spike. To avoid them Fraunie and his friend Dick dress as women. The film makes great play with the consequences including Sherlocko and partner making advances. Meanwhile Sallie, on a city ferry, encounters Spike himself. She temps him into attempting to rob her and she is able to have in arrested. All the characters come together at a police station where confusion continues until Sallie explains who is who.

A rather knock about comedy. Out heroine Sallie is clearly smarter and more able than than the assembled males.

The Detective’s Dog. Produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1912). running time: 11:30 minutes, one reel of 300 metres. Source Archive: Library Of Congress. Music: Meg Morley.

One for Canine fans. Both the opening and closing scenes are missing and explained in on-screen titles. There is also some deterioration, as shown above, but only for a few shots.

Detective Harper’s daughter, (Magda Foy again), brings home a canine waif. She is so attached to this large Bernese Mountain Dog that the parents allow him to stay. Meanwhile the detective is on the trail of a gang of counterfeiters who both threaten storekeepers as well as passing fake bills. Not the brightest member of the Force Harper is trapped in the gangs basement workshop. In a trope found in other silent dramas and still on the go in the Bond era, Harper is tied to a plank inching towards a whirling circular saw. Meanwhile, Harper’s wife is worried a by his absence. The unnamed canine hero is given a coat of Harper to sniff. He sets off and soon finds Harper dangerously close to the saw but helps him break free. We learn the gang are captured and the dog is celebrated by the family.

Our canine hero offers a performance of restraint in the family home but is far more active in the rescue sequence. He is possibly the same dog as Pathé’s 1911 Fidèle / Fidelity but that was made in France by Léonce Perret. Did someone migrate with their companion or was this a relative in the New World?

Greater Love Hath No Man. Directed and produced by Alice Guy Blaché (Solax, USA, 1911). running time: 15:20 minutes. Source Archive: Library Of Congress. Music: John Sweeney. 1 reel, 300 metres; without tinting. There is a 1915 film of five reels with the same title credited to Herbert Blaché; it looks like a mining drama.

This title is a western romance. Set in a mining town in New Mexico. Jake is smitten with the camp flower, Florence [Vinnie Jones]. We see them both in the town saloon as the mail arrives. There is news of a news superintendent for the mining. When he, Harry, arrives Florence is immediately smitten with him; poor Jake is spurned. The superintendent weighs the gold bought by the miners and pays out the value. Some Mexican miners, only identifiable as such from the title card, dispute his valuation. But he forces compliance at gun point. Meanwhile Jake sees the couple in a leafy spot embracing; he is distraught and leans against a tree as he cries. Harry and Florence also meet in the superintendent office. Thus they are caught together when the Mexicans attack the office. Helped by Jake they flee the mob. However, there is only one horse and Jake offers to hold off the mob whilst Harry and Florence ride for help. They find a troop of US cavalry. But Jake is out-gunned by the Mexicans and when they return he dies in Florence arms.

The film will have been shot at the Flushing Studio in New York. The interiors, especially the saloon, are well done. It is not clear where the exteriors were shot but they are very well done. The sequence where Jake watches the couple uses trees and greenery to good effect. And the clearing where we watch the gunfight as Jake holds off the Mexican mob is well done and really exciting.

These early films have few credits. So the researchers have identified Alice Guy’s contributions as writer, director and, often, producer. Some of the cast are known and there seems to have been a stock company of faces including regular leading players like Vinnie Burns and regular character actors like the child Magda Foy. There is little information regarding the craft personnel. It seems that Herbert Blaché acted as production manager and cinematographer for the majority of these titles. One other craft person known is Henri Ménessier who was the set designer on many of these films. He had worked with Guy in France at Gaumont and was sent across the Atlantic to the Flushing Studio; then moving with Guy to the Solax studio at Fort Lee. Clara Auclair discussed his work in one of the presentations at the Conference. She noted that he had a tendency to include alternative spaces alongside the central setting; allowing for particular plot developments. So in The Sewer we see young Oliver in an alcove listening as the gang plan their assault on Stanhope. This is crucial in allowing Oliver to assist Stanhope to escape the clutches of the gang and the final happy resolution.

The Conference organisers plan to make the presentations available date. This will provide an interesting and informative commentary to these fascinating early films. You can get a sense of this; full details on the Conference and screened titles and programme notes are on the web pages. The whole event is a welcome opportunity, especially during a lock down where we are all missing cinema.

Leave a comment