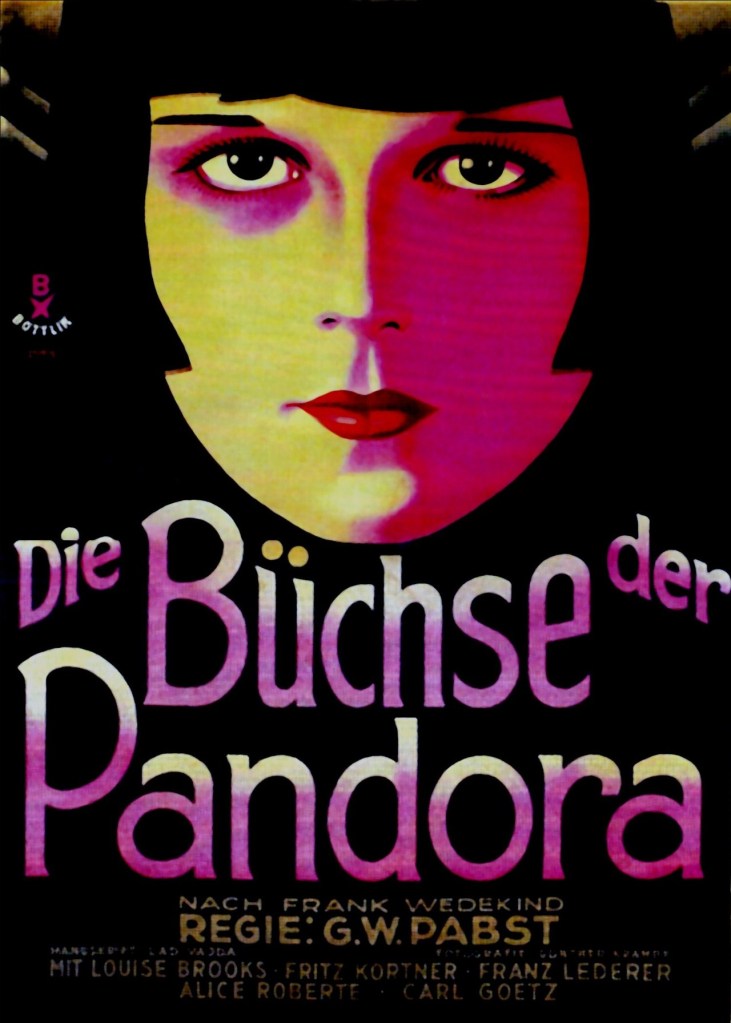

Pandora’s Box / Die Büchse der Pandora, 1929

Posted by keith1942 on January 8, 2022

This is a film classic from Weimar cinema and I was able to revisit it in its original 35mm format as part of the Centenary Celebrations of the Hebden Bridge Picture House. The film has become memorable for a number of reasons. One is the star, Louise Brooks, who worked in the burgeoning Hollywood studio system but also in Europe; and here film-makers bought out a luminous quality to her screen presence. Brooks was an attractive and vivacious and smart actress; her ‘Lulu in Hollywood’ (1974), recording her experiences in the film world, is a great and informative read. Here she plays a ‘free spirit’ whose charisma has a fatal effect on the men that she meets.

In this film she was working with one of the fine directors of Weimar Cinema. G. W Pabst. Pabst was born in Austria but his major career was in Germany. He was good with actors, especially women; his Joyless Street (Die freudlose Gasse, 1925) features three divas, Asta Neilsen, Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. Pabst worked particularly in the ‘street’ film genre and in complex psychological dramas. He was noted for the fluid flow of the editing in his films. Following ‘Pandora’s Box’ Pabst also directed Brooks in the very fine Diary of a Lost Girl / Tagebuch einer Verlorenen, 1929).

One reason for the quality of Pabst’s silent films is the skill and expertise of the craft people working in Weimar Cinema. They led Europe in the quality of their production design and construction; and the development of ‘an unchained camera’ was extremely influential leading to German directors and craft people being recruited to the major Hollywood studios.

The film is an adaptation of an important German play ‘Earth Spirit’ (‘Erdgeist’, 1895) and ‘Pandora’s Box’ (‘Die Büchse der Pandora’, 1904) by Franz Wedekind. There had already been an earlier film adaptation with Asta Neilsen in the role of Lulu (1923); and there is a famous operatic adaptation, ‘Lulu’, by Alban Berg. In the play the character of Lulu is described as “the true animal, the wild, beautiful animal” and the “primal form of woman”.

Brooks, in her chapter on ‘Pabst and Lulu’, records;

“Franz Wedekind’s play Pandora’s Box opens with a prologue. Out of the circus tent steps the Animal Tamer, carrying in his left hand, a whip and in his right hand a loaded revolver. “Walk in” he says to the audience, “Walk into my menagerie”.”

In the play she is an ambiguous character; Pabst and Brooks bring a sense of natural innocence to the character who is much less of a femme fatale than in other versions. Pabst eschews the prologue in the film version but in most ways it is the most faithful adaptation of the original. Wedekind’s play was controversial in its time as was this film adaptation. The film was censored in many countries including Britain where there was an altered and ludicrous ending. Brooks again comments:

“At the time Wedekind produced Pandora’s Box, in Berlin around the turn of the century, it was detested, condemned, and banned. It was declared to be “Immoral and inartistic”. If in that period when the sacred pleasures of the ruling class were comparatively private, a play exposing them had called out the dogs of law, how much more savage would be the attack upon a film faithful to Wedekind’s text which was made in 1928 in Berlin, where the ruling class publically flaunted its pleasures as symbol of wealth and power.”

Her comment points up the context for the film. The reputation of Berlin in particular was for social and sexual licence. Brooks describes some of this. The effect on cinema was that, as in this film, writers and directors frequently addressed issues avoided in other cinemas and, again as with Pabst, took an unusually liberal line.

The film opens in Berlin with Lulu’s many male admirers: we have major German film actors, Fritz Kortner as Dr. Ludwig Schön: Francis Lederer as Alwa Schön: Carl Goetz as Schigolch: Krafft-Raschig as Rodrigo Quast: and also Countess Augusta Geschwitz (Alice Roberts). Here one gets a sense of the social whirl of the capital; often seen as decadent from outside. An important scene is set in the theatre backstage as Lulu prepares for her entrance in an exotic costume. Here we see admirer and performer Rodrigo. The focal point in the sequence is the stage-manage who constantly rushes to and fro pushing the show along. Pabst, and cinematographer Günther Krampf, under cranked the scene so there is a real sense of frenetic rush. The stage manager’s problems are exacerbated by Lulu, who is Schön’s mistress and jealous of his fiancée, and so suborns the bourgeois and wrecks the engagement.

The film moves to the post-wedding celebration for Schön and Lulu. Lulu is not only the bride but the focus of attention of all the participants. In particular Lulu spends time with Alwa. Schön, by now smitten with regrets and fears, considers suicide but it is Lulu’s hand that fires the fatal shot. The audience do not see the actual act, merely the drifting smoke from the revolver.

Lulu is now brought to trial and she is seen in the dock in her black widow’s weeds. The prosecutor indulges in overblown rhetoric; citing the myth of Pandora in his argument for her guilt. Found guilty Lulu is rescued by a diversion by her friends, including the Countess. He we see a group of lumpenproletarians who effect the rescue; a sign of the low class situation of Lulu and, in particular, Schigolch.

Leaving by train Lulu meets another admirer, Michael von Newlinsky as Marquis Casti-Piani. He suggests a place to hide out; an illegal shipboard gambling den. The ship is another site of frenetic activity; and again Pabst and Krampf use slight under cranking to provide a sense of almost hysteria at the gambling tables. In this sequence both Rodrigo and the Marquis blackmail Lulu for money. The countess accounts for Rodrigo. And Schigolch enables Lulu to flee the ship with Alwa. Here we get a shot of cross-dressing which emphasises the androgynous quality in Brooks’ performance.

Finally the trio end up in the East End of London; a night-time setting full of noir-like shadows. This is end of Lulu’s downward spiral. The grim sequence of events is counter-posed with the activities of the Salvation Army. Wikipedia has a line on the action of the Production Company attempting to address Britain’s censorious cinema culture. In a changed ending Lulu is saved ‘from fates equal to death’ by conversion. I have never seen this version but the British Board of Censors records show that the British release was up to half-an–hour shorter than the German original; [presumably at similar running speeds]..

Pabst clearly bought out an unrealised quality in Brooks’ acting. She records he4r feelings on this;

“When I went to Berlin to film Pandora’s Box, what an exquisite release, what a revelation of the art of direction, was the Pabst spirit on the set.”

She also records how effectively Pabst worked with Alice Roberts, who was not enamoured with playing a lesbian character. The performances from all the actors are really fine; notable in that their characters are almost completely unsympathetic. Some of the narrative may appear fanciful and, as with Wedekind’s original, is as much about symbolising society as preventing it realistically; but the narr6iave remains convincing.

The editing of the film is well up to Pabst high standards. The development of characters and plots flow along; and, in what is a slightly long film, maintains interest and development. Pabst also has a discerning eye for the detail of the mise en scene. The theatre sequence is full of interesting action in the back ground to the actions of the key characters. And the ship board sequence is full of fine detail: some of it obviously symbolic like the stuffed crocodile hanging near the ceiling: but also in creating atmosphere in the brief shots of the ship itself, its shadowy appearance suggesting the decadence beneath deck.

Praise is due to the cinematography of Gunter Krampf. He s clearly played an important role in the creation of the visual effect of the film. Brooks records’

“He [Pabst] always came on the set as fresh as a March win d, going directly to the camera to check the setup, after which he turned to his cameraman, Günther Krampf, who was the only person on the film to whom he gave a complete account of the ensuing scene’s action and meaning.”

This film is rightly now a classic, and like many masterworks, it is as much a collective achievement as an auteur product. It is also rare in that it is not often that such an interesting commentary on the film is provided by one of its key performers. The uninhibited depiction that Brooks notes led to censorship problems across many territories, not just in Britain. Happily in recent decades there have been several restoration which have returned the film to almost its original release length.

Originally running for 133 minutes; the print screened had most of the cuts restored and ran for 130 minutes at 20 fps. It had English rather than German title cards; in plain black and white and in an aspect ratio of 1.33:1. I was unsure what the print would be like beforehand as the details held on the print by the BFI are sparse. The projectionist advised me that he had set the lamp higher because of the darkness of so9me sequences. It appeared to have been copied from a second-generation positive print rather than original negatives but the image quality was reasonably good. In fact, I soon recognised the print because there was a slight warping in the wedding sequence and again later in part of the ship board sequences. It was the same print screened at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 2007. This was a print restored in 1998 by the Cineteca di Bologna and the Cinémathèque Française; recorded as 3018 metres, whereas the original had been 3255 metres.

It had a live musical accompaniment sponsored by Cinema for All – Yorkshire and performed by Darius Battiwalla. Darius is a fine and experienced accompanist and he provided an accomplished score which match the varied moods of the film.

Diary of a Lost Girl / Tagebuch einer Verlorenen Germany 1929 « Early & Silent Film said

[…] Pandora’s Box / Die Büchse der Pandora, 1929 […]