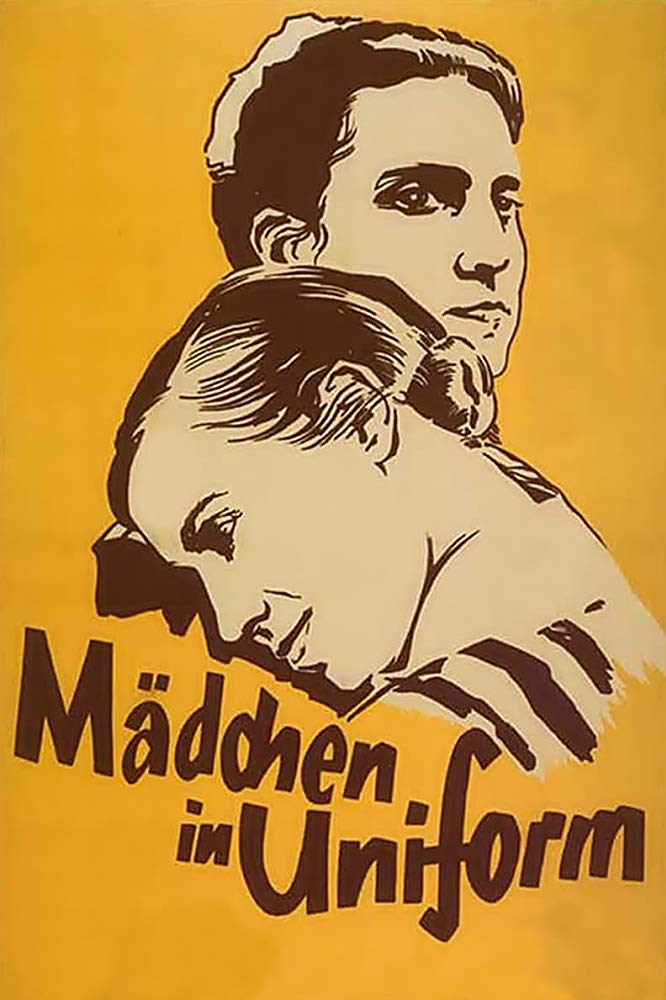

I was able to see this film in a 35mm print at a Festival and then later at the Lincoln Centre in New York. It is a recognized classic: of German film: of gay movies: a predominately women production: and an early sound film. It is set in an oppressive girl’s school, dominated by traditional Prussian values, where female desire produces resistance and rebellion to authoritarian control.

At the start of the film young Manuela von Meinhardis (Hertha Thiele), 14 years old, is enrolled at the a boarding school for the daughters of aristocratic and generally wealthy military families. Apparently all the girl students and all the German teaching staff have surnames preceded by ‘von’ this was the traditional identification for the nobility. We do not learn the surnames of the manual staff but one can assume they do not enjoy the preposition ‘von’. The Headmistress (Emile Unda) is a repressive figure who aims to inculcate a traditional subservient role on the girls, as

‘God willing … mothers of soldiers”.

The repressive regime is symbolized in many ways. For the majority of time the girls have to wear black and white striped dresses rather resembling prison dress, and black pinafores. Hair is short and plaited; the short hair is like the fashion of the 1920s, but any longer hair is pinned back in buns, even for the teachers. Manuela is first seen wearing a hat, but later her hair is shown as tied back in a loose lock; she soon has her hair pinned in a bun. Clothes from past students are re-used, so Manuela gets an ill-fitting dress. Intriguingly it includes a hidden heart symbol by the previous owner for a teacher, Fräulein von Bernburg. We learn that books bought in by students are banned; the volume that Manuela carries is not identified but an illustration on a page suggests melodrama, even the gothic. The regime is organised on military lines and the food is generally basic, rather as for infantry.

“Prussians are raised on hunger.” [The Headmistress].

The milieu of the film is set in the opening. A bell chimes over a blank screen followed by a series of exterior shots of Prussian architecture, the sound of military bugles and then chiming bells. These types of images recur throughout the film, rather in the manner of the ‘pillow shots’ common in films by Ozu Yasujiro. We then see marching troops and there is a cut to a line of regimented girls, in the striped dresses, filing though a park.

There follows the interior in an office where Manuela’s aunt has bought the young girl. She is seen by a Fräulein von Kestern, who seems to be the assistant to the headmistress; we later see her bringing bills for signature to the head. Manuela stands by the window, possibly watching the line of girls marching by. We learn that her father is an officer whilst her mother died whilst she was young. The aunt stresses her sensitivity and emotionalism; and in an unexpected gesture Manuela offers a handshake to the surprised teacher.

Manuela is shown round by Marga (Ilse Winter), a young pupil who we find is both a teacher’s pet and generally supportive of the values of the school. Manuela finds out about the uniform and regimentation of the school., As the pair visits different areas the school building appears as a labyrinth of corridors, hallways and two stairwells; one reserved for staff and visitors, the other a high square structure frequently presented in a high angle shot looking down the stairwell and with guard rails on its sides. It runs to six levels but we only see two or three of these; dormitories, staff rooms, including that of the head: and the ground floor hall class rooms, dining rooms: with the kitchens seemingly in the basement.

The young women that Manuela meets clearly find the regime repressive; all come from a similar background with the double-barreled surnames including the ‘von’. One particular rebellious girl is Ilse (Ellen Schwanneke); when we first see her in a choir she is singing her invented words to what is likely actually a hymn. In the dormitory she shows Manuela her pin-ups on the back of her cupboard door, including a popular film star with ‘sex appeal’. Two other girls gaze with rapture at a photograph of an almost naked male. And a group the girls all express their admiration for what we discover is the one liberal teacher in the establishment, Fräulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck); ‘The Golden One’.

Manuela is considered fortunate in being allocated to the dormitory under her care, where Ilse also sleeps. It is a sign of Ilse’s rebellious character that her bed is the only one that is not in line with the uniform layout. We see the nightly ritual where Bernburg stops at the bed of each girl and kisses her chastely on the forehead. Ilse, in the next bed to Manuela, grows in excitement as her turn approaches. And when it is Manuela, whose emotionalism is already apparent, the young girl throws her arms around Bernburg who kisses her, not on the forehead, but full on the lips.

It becomes apparent that Manuela develops a serious crush on Bernburg. The teacher tries to discourage this whilst also in other ways encouraging it; for example, by giving Manuela a slip to replace her own tattered garment. We see a class under the tutelage of von Bernburg. She asks Edelgard (Annemarie von Rochhausen), Manuela’s fellow student, to recite a verse from a German hymn;

“Oh, that I had a thousand tongues and a thousand mouths …”

taken from a Passion hymn by a Lutheran theologian Johann Mentzer. Manuela is asked to continue it with the second verse, she becomes tongue-tied. Whilst the hymn is addressed to the deity the passionate words might express Manuela’s emotional desire for Bernburg. This scene includes one of two instances of a lap-dissolve between Bernburg and Manuela.

Meanwhile there is a rebellious spirit among the girls, notably on the part of Ilse. She defies the rules by writing and smuggling a letter home complaining about the inadequate food. The letter comes back undelivered and Ilse is disciplined. At a teacher’s meeting it is apparent that Bernburg is the odd one out,

“I want to be a friend of the girls”;

espousing liberal views frowned on by the head, who is supported obsequiously by the other teachers.

Ilse and Edelgard in line

Matters come to a dramatic head when the school performs Schiller’s play Don Carlos as part of a celebration for the headmistresses’ birthday. Ilse, as punishment for her letter, is removed from her role as Domingo in the cast. Ilse packs to return home but von Bernburg persuades her to stay and watch the play.

Manuela, displaying acting talents, is cast as Don Carlos. The play is selected as a classic of German literature. This rather overlooks the play’s expression of liberal values and opposition to censorship. In fact, during refreshments for visiting guests one woman wonders if Schiller is

‘sometimes rather free’.

We see three short scenes from the play The stand-in as Domingo tells Don Carlos,

“Give us Freedom of thought.”

Then Don Carlos faces the Queen, “your mother”: she is in fact his step-mother for whom he has unrequited love: Faced down he retires without expressing his passion. The performance apparently ends here rather than with the rebellion in Schiller’s original.

The play is a success warmly greeted by the audience of girl students, teachers and guests., including praise for that by Manuela. Von Bernburg tells her that she has the potential to become an actress. Later, Manuela asks Ilse about von Bernburg’s response during the play, to which Ilse responds

“the way she looked at you, you can’t imagine…”

Whilst the guests have tea with the Headmistress the girls are served a punch made in the kitchen. Most of the girls find it unpalatable but Manuela, high on emotion, drinks copious amounts and is soon drunk. She then declaims to the assembled girls, telling of von Bernburg’s present of an undergarment and ending,

“ She loves me.”

followed by

“Long Live our beloved Fräulein von Bernburg.”

The last is heard by Fräulein von Kestern who comes to see what all the noise is about.

This leads to the final reckoning for Manuela and von Bernburg. Manuela’s is not expelled because of an unexpected visit by a Royal princess, [possibly a Grand Duchess], and the headmistresses desire to avoid a scandal. This event sees all the girls change their stripped dresses for long white ones. The girls plan to tell the princess of Manuela’s travails but their nerve fails them.

The headmistress calls von Bernburg to her office where there is a confrontation. Von Bernburg tells the headmistress

“What you call sing, Headmistress, I call the spirit of love.”

The headmistresses response is that there can be

“no more contact between you and her.”

Returning to her room von Bernburg is met by distraught Manuela. Ignoring the headmistresses’ stricture she sends Manuela to her room. There she tells the girl that she is to be segregated in an isolation room and that she, will not be able to see her;

“You’re not allowed to love me in that way.”

Manuela leaves; von Bernburg starts to follow her but is confronted by the Headmistress who tells her that

“I will not permit revolutionary ideas …”

and that von Bernburg will leave the school that day.

The distraught Manuela heads for the stairwell that connects the various floors for girls and staff.

This is a four-sided tower, six floors high, a stone or concrete structure with metal railings all the way up; it has a different and starker looks that the other parts of the building. . As Manuela climbs the stairs she recites the ‘Our Father’. Meanwhile, the other girls realise that she is missing and start to search for her. Soon they are running round the building, in and out of rooms; there is a growing hysteria as if Manuela’s heightened emotional state has affected the whole school. Manuela reaches near the top of the stairs, climbs over the railings and is clearly preparing to jump. A high angle shot down the stairwell shows girls on every landing. Her close friends, including Ilse and Edelgard, climb up and pull her back over the railings.

The headmistress arrives and asks,

“Did everybody go mad?”

To which von Bernburg responds

“The girls have prevented a tragedy.”

Manuela and her friends remain at the stop of the stairwell, the girls crowding down the staircase along with Miss von Bernburg. The headmistress turns and descends the stairs past the shocked girls and then walks slowly down the ground floor corridor in a reverse shot which ends with a fade-out to ‘The End’. There is an air of defeat in her manner. Yet it is not clear what will happen now to Manuela or whether von Bernburg will remain or leave the school. It seems likely that the hegemony exercised over the school girls will have been severely damaged.

The film presents a critical view of traditional education in Germany: of the Prussian values that remind influential in Weimar Germany, even after the changes following World War I: and celebrates a subversive set of relations between women. Manuela becomes a disruptive force in the authoritarian school: the absence of a mother means that she is more exposed to the dominant Prussian military masculine culture. She arrives in a school where there is already a groundswell of resistance both to the repressive culture and the mean-spirited provisions. The possibilities of resistance are embodied in the character of Ilse; when we first see her she is already, in a guarded manner, expressing rebellion. The girls are involved in half-expressed sensual relationships. This is apparent in the desire expressed over imagery of the absent males in the school. But it is also there visually in the shots of pairs of girls involved in physical contact and in references in their dialogue to ‘crushes’ both on other girl students and on the teacher von Bernburg.

Miss von Bernburg is an ambiguous character; a point made in the first comment that Manuela hears from a fellow student Ilse,

“You never know how to take her. First she throws you a terrible look. Then, all of a sudden, she is awfully nice. She is also a bit creepy.”

Her first name is Elizabeth, only used once in the dialogue by the wardrobe mistress explaining a ‘heart’ symbol in the garment given to Manuela. In her official persona she combines an emphasis on discipline with a warmth towards the girls. In Manuela’s case she twice makes the point that their relationships is that between a teacher and a student. However, in her non-verbal responses she suggests something more. Isle describes her response whilst watching Manuela’s performance in the play. And twice in the film there is the use of an overlapping dissolve between a close-up of Manuela and of von Bernburg; a technique that suggests a powerful bond between the two women. Her rejoinder to the headmistress of ‘the spirit of love’ also suggests something of desire. Apparently the play had s similar ambiguous emphasis but that there were some productions which emphasised a maternal rather than a love relationship; clearly an attempt to tone down the subversive quality in the drama.

These characteristics in both the girl students and in the one liberal teacher are counterpointed by the headmistress and the subservient relationship with her by the other teachers. The headmistress emphasises traditional roles for the students and the other teachers appear to support this. There is also clearly a rivalry between von Bernburg and the other teachers which seems to relate to her greater effectiveness as a teacher and in her positive relationship with the students. It is interesting that the manual staff in the school, seamstress, nurse and kitchen maids do not seem to share the values of the teachers. At times their brief comments are caustic and in the case of Isle’s letter to home actually subverting the discipline of the school. There is a 1958 version of the play produced by France and West Germany. It appears to soften the subversion: the play performed is ‘Romeo and Juliet’, a less critical choice in the context of the school: and the plot synopsis suggests that it also softens the ending though including the attempted suicide.

The key influences on the film are the director Leontine Sagan and the writer of both play and film, Christa Winsloe. Sagan was a film actress and this was her first work as director. It seems that she bought a fairly co-operative approach to the production. Winsloe was assisted by another writer, Friedrich Dammann. Her play was titled Gestern und heute (‘Yesterday and Today’) (1930). she was known as a lesbian; and orientation that Sagan may have shared. Both women and Dammann left Germany after the ascent of the Nazi regime. However, the producer, Carl Froelich continued working in Germany right through the war and in the 1950s. Heitha Thiele, who played Manuela, also left in 1937. Dorothea Wieck did make some films abroad but continued living in Germany where she was married to a Baron reckoned to be influential in Nazi circles. All of these key characters contributed very effectively to the screen production.

The sets of the film were chosen by Sagan. Much of the film was shot in an actual boarding school though the impressive stairwell was found in a separate building. The actual geography of the school in the film is not that clear. There is a reception room on the ground floor off the hall where visitors are greeted. The Headmistress’s room is up the wide front staircase, presumably on the first floor. Oddly, in the final shot she does not appear to be going to her office, though it may be that the only access is the mains staircase. The classroom also appear to be on the ground floor. At least one dormitory is on the first floor, the others may be there or on other floors. The wardrobe is on the third floor and the hospital room may also be there. The rooms of the teachers seem to be on the fourth floor. What is on the fifth or sixth floor is not clear though the ‘isolation room’ is possibly up there. The square almost prison-like staircase appears a number of times, including the railings that line and surround it. At least one shot down the stairwell is used more than once, so it is not easy always to decide which floor is in use by the characters in this scene.

The opening credits only include Sagan, Winsloe’s play, Froelich and the lading cast members. The cinematography, by Reimar Kuntze and Franz Weimar. I would reckon that Kuntze was the main cinematographer; he had worked on [among other films] Walter Ruttman’s distinctive Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt / Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. The filming is sharp, using mainly frontal set-ups but also including many large close-ups. There are frequent pans and occasional tracking shots; the latter tending to track in on a character. The camera work also uses shadow very effectively. The dormitory scene where von Bernburg kisses the girls goodnight has a soft, romantic feel. But later we see Manuela visited by the headmistress and the shadow of bars falls across her. And there are the two distinctive lap dissolves of von Bernburg and Manuela.

The film was edited by the Oswald Hafenrichter, who later edited The Third Man (1949). The majority of scenes are brief and the film uses frequent intercutting between parallel settings and characters. Some of this is about plot; so there are cuts between the headmistress and von Kestern stressing economy to THE girls discussing food or the lack of it. Others highlight the operation of the school and its repressive qualities. So we see Ilse rehearsing a scene where her lines involve an intercepted letter which is cut to the scene where the Headmistress and von Kestern discover her secret letter. There is a stark scene when von Kestern confronts the girls after Manuela’s outburst. A close-up of von Kestern makes her look like one of Eisenstein’s villains whilst the reverse show shows the girls huddled against a wall. And there are an interesting selection of exterior shots. There is one shot of the girls outside the building on a Sunday afternoon. And there is the shot at the beginning when a shot of marching troops cuts to a line of marching girls in the school uniform. Preceding this has been a number of insert shots of architecture and statues with a Prussian and militaristic feel. This type of insert occurs twice later in the film, including a shot that precedes the girls being marched to prayers in the hall. These shots emphasise the dominant feel of conservative and militaristic values in the school.

The music is by Hanson Milde-Meissner, who had a long career in film. The music track includes trumpets and bells in the insert shots and both of these are repeated in the music that accompanies much of the action. At the end, as the Headmistress walks slowly down the corridor, w hear again a trumpet; this time with a melancholy air that resemble The Last Post.

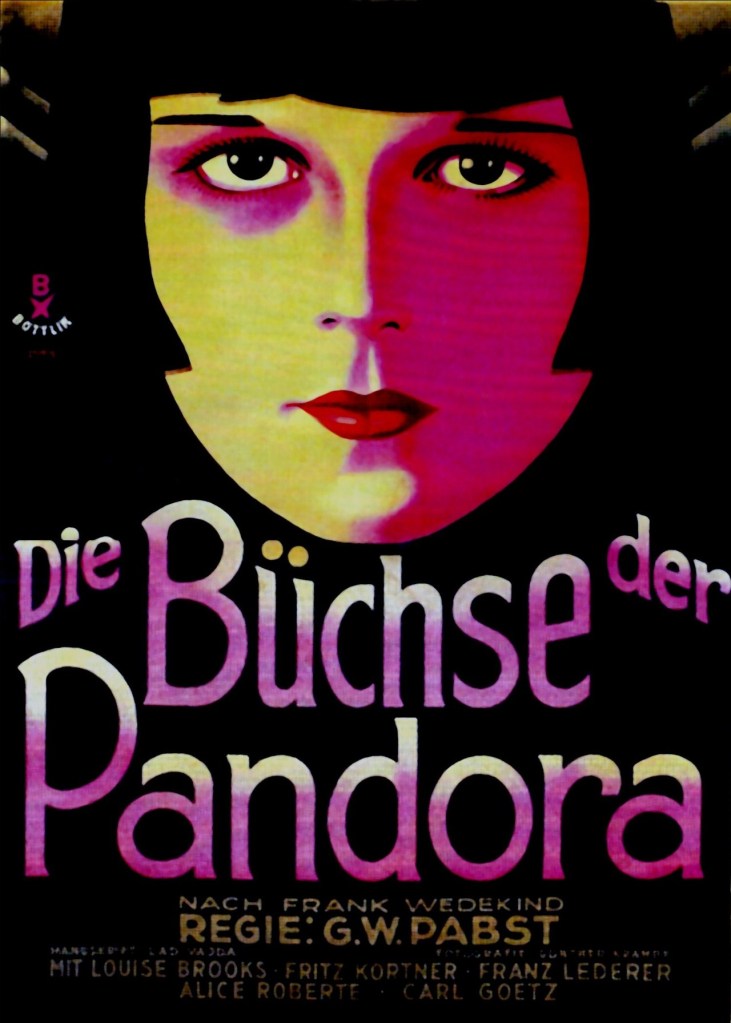

All these contributions come together in a powerful and effective movie. It also offers a clear and subversive drama about sexual orientation and authoritarian control. The sexual element was something that occurred frequently in Weimar cinema. As early as 1919 a film entitled Anders al die Andern / Different from the Others dramatised the situation of homosexuals. However, the result was that new censorship laws were passed and the film was only allowed in specialised screenings; the Nazi later banned the film. A reconstructed version was screened as part of the Weimar Programme at the Berlinale. Subversive treatment of heterosexuality managed to pass censorship laws; notably in the 1929 Die Büchse der Pandora / Pandora’s Box.

In one way Mädchen in Uniform is a last example of Weimar’s liberal film output. And it was successful both in Germany and abroad. It did suffer from censorship. In Germany it was at first banned for young people, a revealing restriction. In 1932 there was a shorter cut version, but even this was banned by the Nazi. There was an initial ban when it was released in the USA but this was lifted. I have not found any indication that it was censored in Britain.

The quotations are from the English sub-titles in the BFI version of the 2018 digitised version from Deutsches Filminstitut & FilmmuseumThe original film was in early sound ratio, 1.20:1; not all video versions or stills are in this ratio.