The on-line edition of the Kennington Bioscope presented a special selection of films from London-born music hall and silent film comedian Fred Evans (1889-1951) showcasing his celebrated comedy character, the prodigious ‘Pimple’, whose popular antics, with over 200 films to his name, proved to be a precursor of many British comedies to come. Hailing from a theatrical family and born in the same year as Charlie Chaplin, they were childhood friends and between them they dominated the comedy box office takings of the ‘teens in the UK. Streamed on Wednesday March 10th and from then on.

Fred Evans appeared in films from 1910 until 1922, though there are only two titles after 1918. His films were apparently popular with British audiences but I do not think the comedies travelled outside Britain and, as can be seen, they typify a particular British comic film character, who is out of sync with the world and the humour tends to slapstick and disaster-prone events.. The films were predominately one reelers and usually scripted by his brother Joe. The duo started out at the British Studio Cricks and Martin in 1910. This was a studio that operated from 1901 until the late teens under several titles. By 1910 the studio was based near Croydon. Evans’ early screen appearances for Cricks and Martin were as ‘Charley Smiler’, a disaster-prone character dressed as a swell.

In 1912, Fred and Joe Evans began working at the Ec-Ko studios in Teddington, and set up their own production company, Folly Films. Cricks and Martin retained the copyright on the ‘Charley Smiler’ character so Fred devised his new character, ‘Pimple. ‘Pimple’ was an accident prone comic character, rather grotesque in appearance; his choice of name suggests this. A frequent speciality was parody of more upmarket productions, often including title cards with obvious puns.

Charley Smiler Joins the Boy Scouts, Crick and Martin, (1911). This is a short film featuring Fred Evans original character. Charley is clearly out of place, a young man among young boys. And his scrapes show a similar misfit with the activities.

Making A Living (USA 1914) The first film featuring Charlie Chaplin at Keystone. This provided a comparison of the two comics, though Chaplin’s title is three years later. And the Keystone Studio has higher production values and sharper technical application.

The Adventures of Pimple: The Battle of Waterloo (1913) A parody of the then recently released British and Colonial Films’ epic depiction of the famed battle (1913). The film has some good comic ideas but rather labours the parody. The actual battle starts promisingly with Napoleon and Wellington meeting and a large number of extras. And there is one good gag about cannon balls. But the cinematography, using exteriors, does not really develop the situation

Pimple Has One (1915) A servant fetching wine gets drunk and has trouble with the police. This title is incomplete. The opening has an ingenious idea; the camera is canted to represent the skewed view of the tipsy servant.

Will Evans the Musical Eccentric (1899) Fred Evans’ Uncle Will demonstrates some of his impressive stage skills. This is a film of the stage performance of an Evans’ family member.

Coventry scenes featuring Fred Evans. Evans on tour during the war years and exciting the attention of a fairly large crowd.

Pimple’s Part (1916) Pimple tries to be an actor. An incomplete title where we watch Pimple trying to learn his lines in uncongenial surroundings.

Pimple’s Pink Forms (1916) Pimple is rejected by the army, so he takes a job delivering official forms – film fragment. Pimple is seen in three locations but two are obviously the same set. The title cards are green, interesting.

Pimple In The Whip (1917) A lord foils a plot to kill his favourite horse and rides it to win. This is another parody of a mainstream title. There are some nice moments with a pantomime horse but the staging is not great and the puns are howlers.

The show was hosted live by Michelle Facey with live and pre-recorded accompaniment from John Sweeney, Lillian Henley, Costas Fotopoulos, Meg Morley, Cyrus Gabrysch and Colin Sell. The digitised aspersions were from the National Film Archive with the exception of ‘Pimple’s Pink Forms’ from the Archive Film Agency.

I have to say that I find Pimple an acquired taste. He is often a buffoon rather than a comic. The production values, in some ways typical of this period in British film, are poor; something that the Keystone title shows up. I do not think that screening the Chaplin alongside Pimple intended to show up the latter but it seemed to me that it has that effect.

Pimple is often clumsy, Chaplin is balletic; even at this stage of his career he dominates the frame in a way that Evans fails to do. All the films are predominately in long shot. However, the Keystone cinematography is at the point where long shots phase into mid-shot. The Chaplin character and his fellow actors stand out more sharply than does Evans and his fellow performers. And the lighting is superior so that Chaplin’s expressions are clear and catch the eye; in many frames Evans does not have an equivalent focus. Along with the cinematography and lighting Keystone has much sharper editing. There is a dynamic flow to the Chaplin title that occurs infrequently in the Evans’ productions.

Fred Evans was apparently votes as very popular in a magazine poll of the period. But, like other British performers, he was easily outshone by the migrant working in early Hollywood. There are some incomplete records of titles screened in 1915 at the Leeds Hyde Park Picture House. There is no sign of Pimple but presumably he would have been in the programmes. However, Chaplin’s early titles are there and already, only a year into his career, there is a visible increase in attendances. The teens are the period when the centre of world cinema is shifting from Europe to the United States. This is especially marked in Britain. The industry failed to match the capital investment occurring in Hollywood. By the end of Fred Evans’ career the British box office is dominated by the Hollywood product. And what is apparent in that period is the increasing gap in the production values of Hollywood over British film.

The Kennington Bioscope is based at London’s Cinema Museum. There are regular screenings of early and silent films, frequently on 35mm prints and with live piano accompaniment. The regular programme was on a Wednesday evenings so not accessible easily from Yorkshire. However, there were also day and weekend programmes; several of which I attended and enjoyed.

The Cinema Museum is sited in Lambeth and took a little finding first time. It is housed in an old fire station and for the last couple of years the Museum has been campaigning to retain the premises. This is a vast and unique collection so it continuance is important. It is rather like an Aladdin’s Cave with all sorts of early cinema items and memorabilia. You can just wander round for an age taking in the variety of the collections.

The Bioscope screenings are relatively popular and presented in a professional manner. The screenings also enjoy musical accompaniment by a team of experienced and talented musicians, well versed in the demands of playing alongside these films with no soundtrack but great images and title cards to enable following the narrative. The Bioscope has also been supported by Kevin Brownlow, the doyen of researchers and writers into early cinema. And many of the other regulars are knowledgeable and well-versed in the arrival and development of film in the late C19th.

As with our traditional cinemas and the series of festivals in Britain and Europe all this has ground to a halt with the lock down,. Now the Bioscope has created an alternative online. Programmes of film and music have been streamed and are accessible on You Tube. There has been some skillful use of electronic and computer technology to make this possible.

The premiere screening offered three early short film courtesy of the Jean Desmet Collection at the Eye Museum in Amsterdam. There was an introduction by a Bioscope member, Michelle Facey. As well as the introduction the programme opened with images of the Museum and the Bioscope. These gave one a sense of the Museum and of these regular screenings. The prints which had Dutch title cards had English sub-titles provided by Tom Higginson. First we had Love and Science / Liefde en Wetenschap, Eclair 1912. This comic story presented an inventor whose obsession causes problems for his fiancé. As Michelle remarked his invention seemed aptly appropriate for lock down viewing. The second film was Mixed Identities a Vitagraph title from 1913. This was another comedy where two sisters cause confusion when they take up employment as stenographers. The films were accompanied live by another member and regular Cyrus Gabrysch. A nice touch was a small inset image showing the keyboard during the accompaniment.

The premiere screening also included Heppy’s Daughter (Val Williamson) in conversation with Tony Fletcher; produced by Film Friends Production (2009). ‘Heppy’ here is Cecil Hepworth, one of the most important and influential of the British film pioneers. Val Williamson reminisces about her father and there are illustrative stills and extracts from Hepworth’s productions, including the seminal canine movie, Rescued by Rover (1905). There are also extracts from sound films and interviews. These have been provided with the help of the Cinema Museum, the British Film Institute and the Hepworth Trust. This is an interesting archival resource on early British cinema.

The next Bioscope programme offered more early titles, again courtesy of the Eye Museum. The programme opened with a Gaumont travelogue from 1910, A Pretty Dutch Town. The views enjoyed stencil colouring which adds to the imagery and there was a pre-recorded piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. The two following short film were both appropriately about ‘social distancing’ Gontran and the Unknown Neighbour / Gontran et la voisine inconnue was from the Eclair Co. (1913). This had an ingenious plot involving romance between two musical neighbours. The Dutch title cards had English sub-titles provided and Cyrus Gabrysch provided the piano accompaniment. Edison’s Over the Back Fence (1913) was another comic treatment of romance. Here two neighbours overcome parental opposition with a wily breakdown of distance. There was a bonus title to the prepared programme with Artheme Dupin Escapes Again / Arthème Dupin échappe encore. Dupin was a popular comic character for Eclipse between 1911 and 1916. The comedy, often slapstick, was heightened by the use of camera tricks. This episode from 1912 shows Dupin outwitting the police.

Programme three had four titles including a transfer of a two reel film. And, as usual, there was an introduction by Michelle Facey, piano accompaniments and [as needed] sub-titling by Tom Higginson.

Patouillard and the Bottle / Las Bouteille de Patouillard is a 1911 title from the French Lux Co. This is a one-reel slapstick comedy. Patouillard was a popular character in this period. He escapades always involved physical humour and cinematographic tricks. In this movie he has to carry a bottle of champagne home constantly warding off disaster. His actions erupt on the Paris streets just like the fizzy contents of his bottle. The piano accompaniment was provided by another Bioscope regular Colin Sell.

The two reel melodrama was from the |hand of D. W. Griffith at the Bioscope Studio. Fate (1913) survived among the paper prints lodged at the Library of Congress and the screening relied on a transfer from a 35mm copy held by a Bioscope member. As was usual with Griffith the plot and morals were starkly drawn. A villainous family threaten neighbours. The most dramatic sequence seemed to threaten the daughter’s cute puppy; fortunately the plot goes awry and the villains scapegrace son suffers the ‘fate’. Mae Marsh played the daughter, and in a more restrained fashion than for he later roles. The father was played by Lionel Barrymore who was as melodramatic as usual. This screening enjoyed a pre-recorded accompaniment by John Sweeney.

The thirds title was another one-reel comedy from the Edison Company, Revenge is Sweet, (1912). The office junior is a prankster, mainly inflicted on the female staff. However, finally, he is caught by his own trick, just deserts. Colin Sell provided music at the piano.

Finally, we had a melodrama from the noted silent director Lois Weber. This was a 1911 title from the Rex Film Company, operated by Weber and her husband., Philip Smalley. This was a one-reel drama tracing the lives of twin sisters, separated when their mother died. This is classic material; think of Griffith’s Orphans of the Storm (1921). The mains drama occurs when the sisters reach adulthood, at which point Lois Weber played both characters. The plot emphasises the different life styles of the pair; one in affluence, one in poverty. Weber was drawn to social issues as well as dramatising the situation of women. The copy used had tinting which added to the contrast. And there was musical accompaniment by Cyrus Gabrysch.

The series had added an earlier presentation at the Bioscope from 2011, ‘Chaplin’s London in Hollywood’. This looks at the London in which Charlie Chaplin lived before he crossed the Atlantic to the USA and Hollywood. It also presents, with illustrated clips, how this fed into his films made in the early years. There is footage of areas of London where Chaplin lived and worked, with maps and stills to illustrate. The clips from films, including The Kid (1921) and the earlier short films are accompanied at the piano by Lillian Henley. There is also an extract from Limelight (1952) where Chaplin recreated the Music hall acts in which he worked. And there are extracts from Chaplin’s Autobiography read by Martin Humphries. The whole presentation was made by David Trigg and now Tod Higginson has added hard-of-hearing sub-titles. The presentation is preceded by a short [incomplete] travelogue in Eclair colour from 1914, Lake Maggiore ‘ / Le Lac Majeure.

The fifth program at the on line Bioscope presented more films from the Jean Desmet collection and a feature length drama from a title preserved in the Library of Congress.

The first short film was a French comedy from 1911, L’abito bianco di Robinet / Het Witte Costuum van Nauke / Robinet’s White Suit. Robinet was one of the characters played by the silent comic Marcel Perez. He made over 200 silent comedies and worked across Europe and in the USA but started in France, still a centre of world cinema in the early period. Michelle Facey provides a lot of information about his career. This Italian title [with Dutch title cards and English sub-titles] charted the travails of the character as his pristine white suit is variously and increasingly blackened in a series of slapstick encounters. A regular pianist Cyrus Gabrysch provided a suitably lively accompaniment.

Then Il Pescara from the Ambrose Film Studio in Turin in 1912. This is a short travelogue that follows the river Aeterno-Pescara from its source to the harbour where it pours into the Adriatic sea. Accompanied by Costas Fotopoulos.

The main feature was from the Library of Congress of a film surviving in a 16mm print and that was restored for video by a crowd-funding organised by Movie Silents This was an adaptation in five parts of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped. The film was made by the East Coast Conquest Films [part of the Edison Co.] and directed by Alan Crossland on a small budget. But the film enjoyed actual locations including shooting the shipboard sequence on an actual brig. In four reels the full narrative is not possible and the film concentrates on David Balfour and Alan Breck. The action is well done and the locations add to the sense of drama. This version retains the tinting of the original. In her introduction Fritzi Kramer pointed out that some of the tinting, for example blue in an night scene , is important indicating the time of day of the sequence. The accompaniment was by John Sweeney.

Programme six presented titles on film-making and film-going. The short Los Angelos / Une promenade dans Los Angelos was a tinted film from 1912. Shots across the city included people in the centre and animals in zoos and parks, including engaging crocodiles and ostriches. John Sweeney provided the accompaniment.

Arthéme Opérateur / Artheme as Projectionist was an Eclipse production from 1910. This comic re-appeared, this time wreaking havoc in a cinema projection booth. There was some clever trick cinematography, chaos with film and equipment and on-screen examples of the early technology. Colin Sell accompanied the title on the piano.

A US set in tinsel town was Photo play Magazine Screen Supplement, circa 1920. The title offered insights into studios and a bevy of then popular screen performers, though the only one still familiar today would be Douglas Fairbanks. John Sweeney was back at the piano.

All three titles were courtesy of the Eye Museum and had Dutch title cards with English sub-titles provided.

The Pictured Idol focused on a young female fan of movies and of a major film star. The story chartered her disillusionment as she encountered the reality rather different from the on-screen fantasies. This was a Vitagraph title from 1912 accompanied by Colin Sell.

‘Four Square Steve’

The final drama was an example of films that survive on the 9.5mm format. This was a format for amateur collectors and there was a huge range of productions presented this way; (see the ‘Vintage Film 9.5mm Encyclopaedia’, Matador 2020]. This was a western produced by Mustang Films in 19126, Four Square Steve. The film featured an early role for the later star Fay Wray. She is the daughter of father whose land is targeted by a family of villains. The young hero saves both daughter and land. There is some excellent location work including a final climax on a disused mine and travelator

Programme seven had a single feature-length drama kindly provided from the British National Film Archive. This is the earliest film version of a stage classic, Hobson’s Choice. The play was written by Harold Brighouse, a member of the Manchester

School of Dramatists. Like the earlier drama ‘Hindle Wakes’, also adapted to film, this story has an affectionate and informed view of Lancashire and a strong central woman character. Percy Nash directed this six-reel film. There are two later sound film adaptations, from 1931 and 1954.

The plot involves a successful owner of a shoe/boot shop with three eligible daughters. Part of the story is about the three women finding husbands but it is also a drama of a family patriarch bested by the women of the house. This version opened up the staging but was predominately studio made and retained a theatrical air. The cast made great play with both the humour and the family conflicts.

Programme eight offered a ‘Bioscope Vacation’, a series of short film travelogues and one drama involving a vacation. Most of the titles were from Amsterdam’s Eye Museum and its Jean Desmet collection. In these cases the original title cards had been replaced by Dutch title cards, here with English sub-titles. Unfortunately this was the first streaming with a noticeable hiccup; one of the audio lines to a musician was lost temporarily. And poor Michelle in her comments found herself without a working microphone. However, at least for me, this was only at the end of a title and ‘normal service’ was resumed.

La perle de la Méditerrannée: Barcelone / Barcelona: Pearl of the Mediterranean was from the French Eclipse Company in 1913. This travel title also had tinting. Cyrus Chrysalis provided the accompaniment.

Constantine / Constantinople was a Éclair title with tinting; though here the print had suffered from the ravages of time and the tints were erratic. Cyrus provided the accompaniment.

Lillian Henley provided the music for Egypt circa 1910. The title covered a range of places rather than the capital Cairo. The colours, tints and tones, were even more erratic on another aged and worn print.

John Sweeney accompanied Turkey / Turkije, a 1915 title from a German company, Radios frankrijk. Here the tinting was more uniform.

Costas Fotopoulos provided accompaniment for two titles;

Beelden uit Piraeus / Pictures from Piraeus And then The Lonely Princess / De Eenzame prinses. This was a Vitagraph set in Venice and with an unlikely romance between a visiting Yank and an European aristocrat. As was often the case with the city of Venice the locale offered scenic vistas and the settings eclipsed the young g lovers.

Programme 9 offered a short film and then a six reel feature.

The Wife and I went Cycling / Une Partie de Tandem was an Eclipse title accompanied by Colin Fell. The cycle ride threw up a series of calamities presented with visual wit.

The feature was In Search of Castaways / The Children of Captain Grant? Les enfants du capitaine Grant, a 1914 adaptation of a picaresque novel by Jules Verne. The original novel from the 1860s ran to 900 pages. The search covered several continents, indicated by the separate sections, South America, Australia and New Zealand. The ‘search’ is rather implausible but leads a little band of would-be rescuers over a vast itinerary. The strength of the adaptation is the use of actual locations; there is an impressive sequence in the Alps. The weakness is the plotting, a factor complained about in contemporary reviews. There are quite a few long title cards, but even so it is not always clear why the characters act as they do. I had figures out the main lines by the end. And the title looks good and the music was fine as well. There is some nice tinting on the title cards.

Programme 10 offered another eclectic selection of short silent films, screened by kind permission of collections held by the Netherlands’ EYE Filmmuseum.

Our Film Stars – Photoplay Magazine Screen Supplement #6 (USA 1919). This was another episode in the series presenting notable film people to fans. James Cruze, who had an extensive career as an actor then moved to direction, most famously with The Covered Wagon (1923). He was, though, outshone by ‘Faithful Teddy’ a canine hero at Mack Sennett’s studio.

Flux The Cat (NL 1929). This was an advertisement for a Dutch tyre firm. The cat was clearly modeled on the famous US character Felix. Both titles were accompanied by John Sweeney.

Colin Sell accompanied Le Dytique (The Water Beetle) FR 1912. A tinted study from Eclair.

L’orgie Romaine (Lions of the Tyrant) (FR 1911). This was a hand-tinted title directed by the key filmmaker Louis Feuillade. One of those mad Roman tyrants looses his savage beasts on his own courtiers. John Sweeney returned to accompany this title.

Le Chien Insaisissable (The Elusive Dog) (FR 1912). This was a canine comedy full of trick cinematography as this elusive pooch appeared and disappeared. Lillian Henley accompanied at the piano.

Old Isaacson’s Diamonds (USA 1915) was an episode from one of the popular series of the period; Kalen’s The Girl Detective. The heroine worked by observation, showing up official detection. Costas Fotopoulos accompanied the title.

The screenings had English sub-titles where there were Dutch title cards. And Michele Facey provided introduction to the movies.

Kennington Bioscope partnered with the BFI London Film Festival 2020 for their online screening of newly restored Australian silent film, The Cheaters (1929). The feature was accompanied by Cyrus Gabrysch.

Programme twelve saw the team bring you a programme of ‘Comedy and Colour’, with nine short films shown by kind courtesy of the Jean Desmet Collection and EYE Collections held by the Netherlands’ EYE Filmmuseum.

Robinet Pescatore (Robinet the Fisherman) (Italy 1914)

A title from Ambrosio with the now familiar comic character. Predictably Robinet, with a massive fishing pole, creates a series of mishaps with numerous hapless victims.

Coloured Views – Pontalier and Niort (France 1924-5)

This is a scenic tour in a mountain region in Eastern France. The title enjoys attractive stencil colour and a varied range of vistas.

John Sweeney provided the accompaniment for both titles.

Les Glaces Marveilleuses (Magic Mirrors) (France 1908)

This was one of the titles made by Segundo Chomón using trick cinematography and stop motion to produce a series of clever tableaus and transitions. The print had finely done stencil colour and an accompaniment by Lillian Henley.

Le Dirigeable Fantastique (France 1906)

One of the delightful titles by Georges Méliès. An inventor has a dream in which his airship leads to crazy events. The film also had early colouring and an accompaniment by John Sweeney.

Le Voyage sur Jupiter (France 1909)

A second title by Segundo Chomón also including a dream sequence, here leading to a magical voyage to the planets. This too had stencil colouring and the accompaniment by Colin Sell.

The Paper Bee (? 1920)

This is a nature documentary presenting an industrious insect in stencil colour. Lillian Henley provided the accompaniment but, unfortunately, there were some audio problems.

Amour de Page (France 1911)

‘The Love of the Page’ showed a servant wooing the daughter of his lord. The complication was an aristocratic rival who is finally un done by a convenient witch.

La Legende des Ondines (Legend of the Sirens) (France 1911)

This was another period drama which a rousing climax. The unhappy protagonist deserts his love for a sensuous siren; this takes place on a shoreline rock with the watery foam overwhelming all involved.

Costas Fotopoulos accompanied both titles.

Madamigella Robinet (‘Miss’ Robinet) (Italy 1913)

Robinet returned in this cross-dressing comedy. Caught in a compromising situation Robinet borrows his mistresses’ clothes. The tilt ends with a delightful sequence where the protagonist is enamoured by a whole host of men and a squad of police.

Colin Sell provided the accompaniment.

A Christmas Special courtesy of the BFI and the EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Featuring a whole array of shorts of Winter and Christmas by the enormous generosity of EYE Filmmuseum and the British Film Institute (BFI). The longest programme to date with twelve titles and, impressively, twelve accompanists. There are the usual introductions by Michelle Facey, accompanied by some guests. And there are English sub-titles where required.

Holland in Ijs (Netherlands 1917) – Scenes from the Netherlands in what was an extremely cold winter for them. It included footage of the ‘Eleven City Tour’, a race held on the canals in years when they were frozen; not that often. A tinted title accompanied by Daan van den Hurk

Expedition to the North Pole (USA 1916) – Animated adventure by airship to the frozen North. The treatment included some satirical jokes about recent expeditions. Accompanied by Cyrus Gabrysch.

Il Natale di Cretinetti (Foolshead Christmas, Italy 1909) – Early film comedian André Deed wreaks havoc with an outsize Christmas tree. Typically that commences with his Christmas mail and then follows with the iconic tree. A title made in Turin and now accompanied by José María Serralde Ruiz.

Ida’s Christmas (USA 1912) – Dolores Costello and John Bunny star in this heart-warming tale from the Vitagraph studios. Ida desires an expensive doll, way beyond the purse of her poor parents. The tale relies on the over optimistic view of the Christmas spirit; especially when involving rich and poor. Accompanied by Colin Sell.

Snowstorm in New York (Netherlands 1926?) – A blizzard paralyses Manhattan. Accompanied by Ben Model.

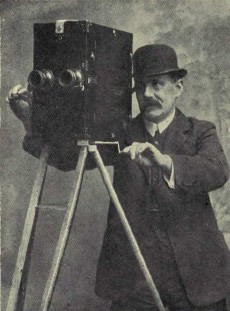

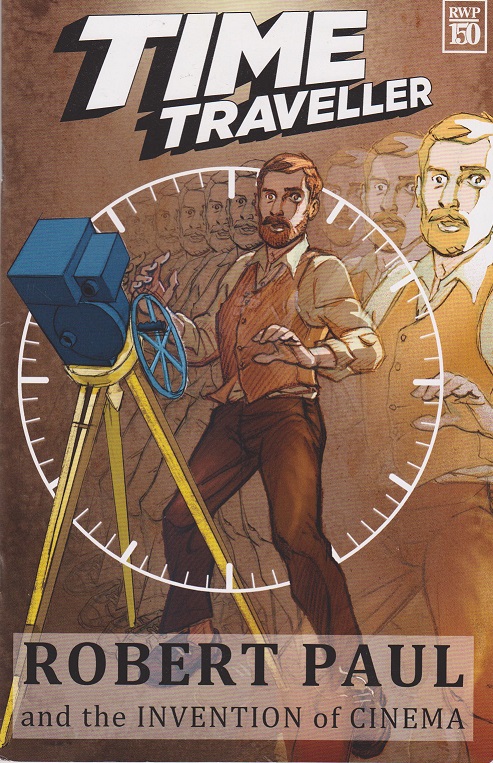

Scrooge; or Marley’s Ghost (Britain 1901) – R.W. Paul’s early and ingenious depiction of Dickens’ seasonal story. This was star screening in the programme. Paul, an important pioneer in early British cinema, produced an adaptation in twelve tableaux. Originally the print was 620 feet but only a version of 327 feet survives in the National Film Archive. The technician expert at the Bioscope, Todd Higginson, used a published synopsis in ‘The Era’ in 1901 to add titles that filled out the missing sequences. So we enjoy a combination of titles and filmed sequences which presented the complete version. Paul’s version did not use the ‘spirit’s of Christmas’ but used Jacob Marley’s Ghost to show Ebenezer Scrooge the past, present and future season. The film was sophisticated for the period with superimpositions and wipes. Accompanied by Meg Morley.

Snowballs (Britain 1901) – Schoolboy scamps besiege passers-by with handfuls of the cold white stuff. This was one of the short titles from the Mitchell and Kenyon collection; which lay hidden until 1994 when by a fortunate discovery they were recovered. Accompanied by Lillian Henley.

Santa Claus (Britain 1898) – The wonder of Christmas. British film-maker G.A. Smith’s film features his children and wife Laura Bayley. Smith was another pioneer on British film and part of what became known as ‘The Brighton School’. He was also inventive and there is a happy use of an iris in this title. Accompanied by Stephen Horne.

The Little Match Girl (Britain 1914) – Percy Nash directs this, the second British adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s heart rending story. This famous story turned up in a number of adaptations; this was an Eye print, thus with Dutch titles and English sub-titles. Heart-rending is right. The ‘little girl’ has a brutal father and must try to sell the matches in the freezing cold and snow., There is a nice use of colour to offer a dream world alternative to the grim reality. Accompanied by Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton, who added ‘Silent Night’ to the emotion.

The Mistletoe Bough (Britain 1904) – An unlucky bride is locked in a trunk in this early film. A sardonic plot and period settings which felt slightly anachronistic. But the grim outcome is effective. Accompanied by Costas Fotopoulos.

Broncho Billy’s Christmas Dinner (USA 1911) – Villainous Broncho Billy finds himself accidentally invited to the Sheriff’s home for the festive repast. In the title it is the Sheriff daughter rather an ‘accident’ that sets up the Christmas repast. There is also a happy coincidence as the present of a medallion is edited together with the arrival of the parson. Accompanied by Philip Carli.

There was a slight technical hitch, rare for the Bioscope, then:

Santa Claus and the Fairy (Britain 1898) – Have you been naughty or nice? Stockings at the ready! A moral just before the festivity. Accompanied by John Sweeney.

Programme 14 of the Bioscope offered three titles courtesy of the Library of Congress archive. There was a five reel programme feature and two short titles. These were introduced as usual by Michelle Facey and the shorts were accompanied by pre-recorded music with a live stream for the feature.

The Day After is a Biograph title directed by D. W. Griffith in 1909 with the plot written by the young Mary Pickford. The film was 460 feet in length. I t was show in the then standard long shot/long take. Set at a New year’s Eve Party and released in January the film presents ‘Remorse’ [Moving Picture World Review]. In this case by the host husband and wife are their over-indulgence of the night before. The film has three basic set-ups: the parlour where the lethal punch is served and where later the couple cope with breakfast: the dance room where the revelries occur: and the bed-room where the toils of the night before are felt. This is a simpler comedy than some of the more complex dramas made by Griffith. Colin Sell provided the music.

H2O (1929) is an abstract film made by Ralph Steiner. He was a photographer and cinematographer who also directed avant-garde films. He was a member of the progressive Film and Photo League. This is title is a study of water, both its situation and, for much of the film, the patterns seen in still and moving water. This was a pioneer work which was highly regarded and influential. Similar avant-garde works were also made in Europe, notably Joris Ivens Regen (Rain) in the same year. Later Steiner worked in Frontier Films with Padre Lorentz Leo Hurwitz and Paul Strand. The film’s pattern formed moving and soothing set of images, bought out by Lillian Henley’s accompaniment.

The feature was Daring Deeds from 1927; a standard release from a small production company, Duke Warne Productions. The AFI Catalogue has links on the output of the company which operated in the 1920s and closed early in the sound era. There are also links to the cast and production members. This is a black and white five reel title with some tinting in the night-time sequences and a bright red tint for the title card.

The plot involves the aeronautics industry and a key aerial race. In order to scupper the opposition thieves attempt to steal the plans of a new model and then actually high-jack the plane itself. They are thwarted by the son of the industrialist who ate first seems rather lackadaisical. There, is, profitably, a romantic tie-up as well. The narrative is very conventional but there are some well-done aerial sequences. Director of cinematography Ernest Smith excelled here. There is some under-cranking in the fight scenes which makes them run pretty fast for modern tastes. And I thought that at one point in a chase sequence that the camera actually ‘crossed the line; but this was early days in studio conventions. Oddly though, after the silent era, Smith was reduced to camera operator.

John Sweeney provided a suitable accompaniment. The whole programme is still up on the You Tube Kennington Bioscope.

Many of the short films whose transfers feature in the Bioscope programmes are from the Jena Desmet Collection at Amsterdam’s Eye Museum. This is one of the Archives listed on the pages of the International Federation of Film Archives as providing free streaming for visitors during the lock down. This is a great resource and there are an amazing variety of early films provided in this way.